At whatever moments you read these words, day or night, there are birds aloft in the skies of the Western Hemisphere, migrating. Scott Weidensaul

Early March on the coast of New Zealand, a Bar-tailed Godwit (Limosa lapponica) gorges endlessly on mollusks to fatten up for its 7,000-mile (11,270 kilometers), non-stop flight to Alaska. In April, a Pacific Golden Plover (Pluvialis fulva) is also feeding constantly in preparation for its long journey from Hawaii to Alaska. Each spring, shorebirds—the long-distance athletes of the animal world—make marathon flights between hemispheres to remote areas in Alaska where they nest and raise young. Migratory birds are the feathered ambassadors of our planet; they connect water, land, air, and us to other people, cultures, and countries far away.

The coastlines of Bering Land Bridge and Cape Krusenstern hold 1,000 miles (1,600 kilometers) of low, sandy beaches, extensive and shallow lagoons, vast and estuaries, mudflats, salt marshes, the occasional cliff habitat, and shallow nearshore environments with extensive barrier islands and sandbars. Bering Land Bridge’s enabling legislation specifically establishes this national preserve to, among other values, “protect habitat for internationally significant populations of migratory birds.” Likewise, Cape Krusenstern’s enabling legislation establishes this national monument to, among other mandates, “protect habitat for and populations of birds and other wildlife.” To that end, we work with collaborators to understand shorebird use of coastal areas in these parks during migration.

Stepping Back in Time

Our ability to manage habitat for birds within both parks is constrained without an understanding of the historical status and variability of waterbird populations. We recently collaborated with Wildlife Conservation Society’s Arctic Beringia Program to assess the historical status of bird species in Bering Land Bridge and Cape Krusenstern, as well as elsewhere in the transboundary landscape of Beringia. Understanding what species are and have been present in Kotzebue Sound provides us with a tool for understanding future changes to the region.

The birds of Kotzebue Sound have been periodically studied since the late 1800s. Joseph Grinnell produced the first thorough survey of the birds of the region from the summer of 1898 to the following summer of 1899 (Grinnell 1900). Periodic, natural history surveys took place through the first half of the twentieth century before being replaced by site- and species-specific work in the late twentieth century. Site-specific studies such as Schamel and Tracy’s Environmental Assessment of the Alaskan Continental Shelf (1979), and Wright’s graduate thesis, Reindeer Grazing in Relation to Bird Nesting on the Northern Seward Peninsula (1979), also provided detailed species lists and encounter histories in their reports. Recent studies conducted during the twenty-first century were varied in this regard. Between 1951 and 2000, natural historians and researchers collectively recorded 159 species, in comparison to 126 species recorded between 2001 and 2012. The vast majority of these species are migratory, with only 30 recorded wintering in northwest Alaska. Fewer records of species made during recent times may be an artifact of the shift from natural history record keeping to more quantitative approaches.

Shorebird Migration in Bering Land Bridge and Cape Krusenstern

Alaska’s nearshore environments are staging areas for many Arctic breeding shorebirds making trips between their overwintering areas and breeding grounds. More shorebird species breed in Alaska than in any other state in the U.S. Thirty-seven species, including several unique Beringian species and Old World subspecies, regularly breed in the region (Alaska Shorebird Group 2008). The extensive saltmarsh and tidal flat habitat of the Chukchi coastline lies at the convergence of three major migration flyways: The East Asian-Australasian (Figure 2), Central Pacific, and Pacific Americas. As a result, birds from five of the seven continents may converge here.

Migration is a dangerous undertaking, and birds face numerous threats throughout their journeys. Frequent population trends for migratory shorebirds show a global pattern of decline (Bart et al. 2007). Their vulnerability is due in part to their frequent dependence on intact networks of coastal and wetland habitats during their long-distance migrations, since these habitats serve as important places to rest and refuel. Addressing the conservation needs of migratory shorebirds involves understanding habitat use and connectivity on a scale that spans wintering areas, migration routes, and breeding grounds Bentzen et al. 2016 (Gratto-Trevor et al. 2012). To understand the use of coastal areas by shorebirds during migration in Bering Land Bridge and Cape Krusenstern, we collaborated with shorebird biologists from the University of Alaska-Anchorage (UAA) and University of Alaska-Fairbanks (UAF) beginning in 2012.

Surveying the Salt Marsh

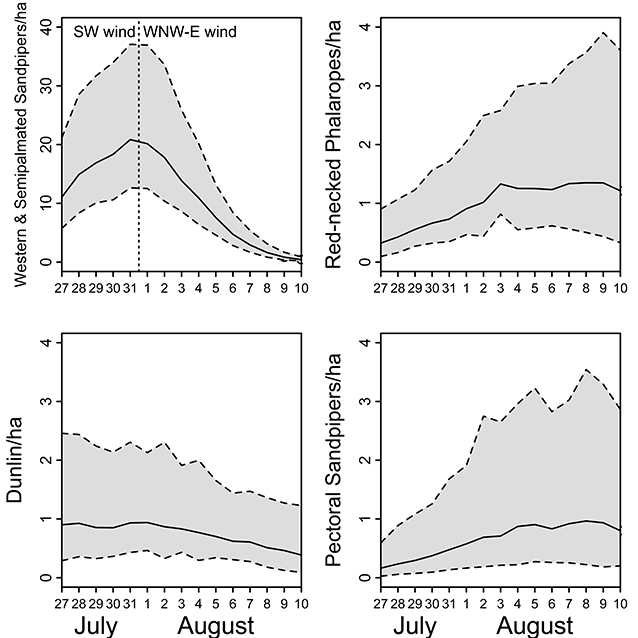

In late July through early August of 2013, three biologists and one intern investigated shorebird use of coastal salt marsh habitat along the barrier island at Ikpek and Arctic Lagoons in Bering Land Bridge. We found that roughly 3,400 Western Sandpipers (Calidris mauri) and Semipalmated Sandpipers (Calidris pusilla) used this 1.15-square-mile (3-square-kilometer) patch of saltmarsh each day, approximately double that reported by Connors and Connors (1985) along the Beaufort and southern Chukchi Sea coasts during the same time period. These results suggest that these lagoons are important stop-over sites for these species. Other shorebirds like Dunlin (Calidris alpina), Pectoral Sandpiper (Calidris melanotos), and Red-necked Phalarope (Phalaropus lobatus) were found in relatively low numbers throughout the survey period (Figure 3). Overall shorebird density peaked at 20.1 shorebirds/hectare on July 31. We observed a total of 20 shorebird species.

Surveying Mudflats from Above

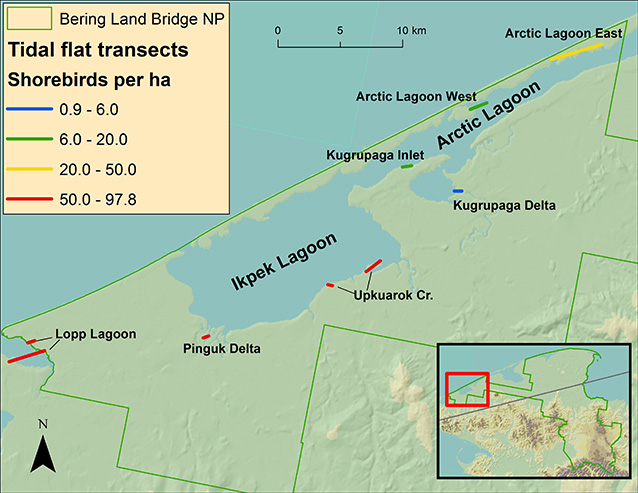

In order to describe shorebird use of coastal areas at a much larger scale, and to identify potential hotspots for staging or migrating shorebirds, we took to the air. In late July and early August of 2014, Dr. Audrey Taylor (UAA) conducted aerial surveys along a random sample of transects in mudflat habitat to count shorebirds. We counted over 26,000 shorebirds from the aircraft between July 28 and August 13. Estimates of shorebird densities were highest for Ikpek and Lopp Lagoons (Figure 4), followed by Shishmaref Lagoon and Cape Espenberg. Shorebird densities were highest during the first half of the survey period with as many as 100 shorebirds per hectare. By the end of the surveys, densities varied between 0 and 60 birds per hectare – a pattern likely due to pulses of shorebirds waiting in these areas to depart with favorable winds.

Species Composition at Sisualik and Cape Krusenstern National Monument

During the same time Dr. Taylor surveyed mudflats from the air, UAF graduate student Megan Boldenow staged at Sisualik Spit at the southern edge of Cape Krusenstern. Her field crew observed 19 shorebird species (on average 11 species per day) stopping over on migration. Approximately 10,300 shorebirds out of 14,482 waterbirds were counted. Western Sandpiper, Semipalmated Sandpiper, Dunlin, and Red-necked Phalarope were the most abundant species, with at least 500 observations made during roughly two weeks. Least Sandpiper (Calidris minutilla), Pectoral Sandpiper, and Long-billed Dowitcher (Limnodromus scolopaceus) were the most common (greater than 100 individuals observed over the course of the season). They even recorded the Stilt Sandpiper (Calidris himantopus), an uncommon migrant along the Chukchi Sea coast that breeds on the North Slope.

Conclusion

From our recent work with collaborators, we gained new insights into shorebird use of coastal areas in Bering Land Bridge and Cape Krusenstern during migration. Tens of thousands of shorebirds use the lagoons and large mudflats of Bering Land Bridge during their post-breeding migrations; most are western and semipalmated sandpipers. These same species are also the most abundant shorebirds stopping over at Sisualik Spit in Cape Krusenstern. The occurrence of an oil or industrial spill near lagoons and mudflats along the coast of these parks during late July through the middle of August would likely affect upwards of 20 shorebird species and at a minimum, several thousand individuals; particularly Western and Semipalmated Sandpipers.

We still need to conduct additional aerial and ground-based surveys along the coasts of both parks to determine peak densities of shorebirds at lagoons and mudflats during the post-breeding period. Longer studies over multiple years will also be necessary to understand the timing of migration on an annual basis. For example, weather conditions in a given year can have a large effect on migration. During our ground surveys at Ikpek Lagoon in 2013, a shift in wind direction precipitated significant declines in the numbers of western and semipalmated sandpipers using salt marsh habitat. It seemed that the birds took advantage of favorable wind conditions to continue their southbound journeys and left the survey area. Without multiple years of information, we cannot identify peak migration periods or know which areas support the highest number of birds. Moreover, the lack of this information will impede our ability to prioritize coastal areas for spill response.

Acknowledgments

We thank the National Parks Foundation and its Coastal Marine Grant Program for funding this work. Natural Resources Preservation Program of the U.S. Geological Survey’s Ecosystems Mission Area and the Oceans Alaska Science and Learning Center also supported the initial pilot work for water birds communities work. Katie Dunbar (U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service/NPS volunteer) and Audrey Taylor provided field support at Ikpek. Jared Hughey provided field support at Sisualik and amazing images of birds there. NPS staff Tara Whitesell, Marci Johnson, and Laura Phillips plus Lisa Clark (U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service /NPS volunteer) were instrumental in field logistics.

References

Alaska Shorebird Group. 2008.

Alaska Shorebird Conservation Plan. Version II. Anchorage: Alaska Shorebird Group. http://alaska.fws.gov/mbsp/mbm/shorebirds/plans.htm.

Bart, J., S. Brown, B. Harrington, and R. Morrison. 2007.

Survey trends of North American shorebirds: population declines or shifting distributions?

Journal of Avian Biology 38:73-82.

Bentzen, R., A. Doudua, R. Porter, M. Robards & D. Solovyeva. 2016.

Large-scale movements of Dunlin breeding in Chukotka, Russia, during the non-breeding period. Wader Study 123(2): 86-98.

Connors, P. and C. Connors. 1985.

Shorebird littoral zone ecology of the southern Chukchi coast of Alaska. p. 1-57. Final Reports of Principal Investigators, Environmental Assessment of the Alaskan Continental Shelf, Biological Studies, vol. 35., Anchorage: NOAA-BLM.

Grinnell, J. 1900.

Birds of the Kotzebue Sound Region, Alaska. Pacific Coast Avifauna (1):1-86.

Gratto-Trevor, C., R. Morrison, D. Mizrahi, D. Lank, P. Hicklin, and A. Spaans. 2012.

Migratory connectivity of Semipalmated Sandpipers: winter distribution and migration routes of breeding populations. Waterbirds 35:83-95.

Schamel, D. and D. Tracy. 1979.

Final Reports of Principal Investigators. pp 289-607. Environmental Assessment of the Alaska Continental Shelf.

Wright, J. 1979.

Reindeer Grazing in Relation to Bird Nesting on the Northern Seward Peninsula: a Thesis. University of

Alaska Fairbanks. Thesis for the Masters of Science.

Part of a series of articles titled Alaska Park Science - Volume 15 Issue 1: Coastal Research Science in Alaska's National Parks.

Last updated: November 15, 2016