Following the Confederate retreat from South Mountain, Lee considered returning to Virginia. However, with word of Jackson's capture of Harpers Ferry on September 15th, Lee decided to make a stand at Sharpsburg. The Confederate commander gathered his forces on the high ground west of Antietam Creek with Longstreet's command holding the center and the right while "Stonewall" Jackson's men filled in on the left.

"There was something weirdly impressive yet unreal in the gradual drawing together of those whispering armies under cover of night-something of awe and dread, as always in the secret preparation for momentous deeds." Private Edward Spangler, 130th Pennsylvania

Preparing to Attack

National Archives and Records Adminstration

The Confederate position was strengthened with the mobility provided by the Hagerstown Turnpike that ran north and south along Lee's line; however there was risk with the Potomac River behind them and only one crossing back to Virginia. Lee and his men watched the Union army gather on the east side of the Antietam.

Thousands of soldiers in blue marched into position throughout the 15th and 16th as McClellan prepared to drive Lee from Maryland. McClellan planned to "attack the enemy's left," and when "matters looked favorably," attack the Confederate right, and "whenever either of those flank movements should be successful to advance our center." As the opposing forces moved into position during the rainy night of September 16th, one Pennsylvanian remembered, "...all realized that there was ugly business and plenty of it just ahead."

The Battle of Antietam

Library of Congress

The twelve hour battle began at dawn on September 17th. For the next seven hours there were three major Union attacks on the Confederate left, moving from north to south. Gen. Joseph Hooker's command led the first Union assault. Then Gen. Joseph Mansfield's soldiers attacked, followed by Gen. Edwin Sumner's men as McClellan's plan broke down into a series of uncoordinated Union advances. Savage, incomparable combat raged across the Cornfield, East Woods, West Woods and the Sunken Road as Lee shifted his men to withstand each of the Union thrusts. After clashing for over eight hours, the Confederates were pushed back but not broken, however over 15,000 soldiers were killed or wounded.

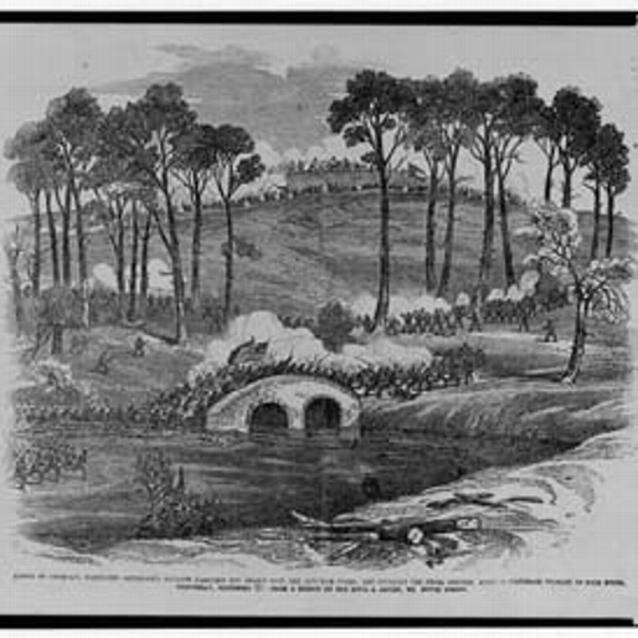

While the Federal assaults were being made on the Sunken Road, a mile-and-a-half farther south Union Gen. Ambrose Burnside opened the attack on the Confederate right. His first task was to cross Antietam Creek, spanned by the bridge that would later bear his name. A small Confederate force, positioned on higher ground, was able to delay Burnside for three hours. After taking the bridge at about 1:00 p.m., Burnside reorganized for two hours before moving forward across the arduous terrain--a necessary and critical delay. Finally the advance started only to be turned back by Confederate General A.P. Hill's reinforcements that arrived in the late afternoon from Harpers Ferry.

Neither flank of the Confederate army collapsed far enough for McClellan to advance his center attack, leaving a sizable Union force held in reserve. Despite over 23,000 casualties of the nearly 100,000 engaged, both armies stubbornly held their ground as the sun set on the devastated landscape.

"Legs, arms, and other parts of human bodies were flying in the air like straw in a whirlwind. The dogs of war were loose, and `havoc' was their cry."

-Soldier in the 4th Texas

The Bloodiest Day in American History

Library of Congress

Seldom had Lee's army fought a battle so strenuous and so long. "The sun," a soldier wrote, "seemed almost to go backwards, and it appeared as if night would never come." From dawn to sunset, the Confederate commander had thrown into battle every organized unit north of the Potomac. Straggling in the days preceding Antietam had reduced Lee's army from 55,000 to 41,000 men. This small force had sustained five major attacks by McClellan's 87,000-man army--three in the West Woods and the Miller Cornfield, and those at the Sunken Road and the Lower Bridge--each time the outcome hanging in the balance.

Surveying the ground the next day, Lee's officers informed him that Federal batteries completely dominated the narrow strip of land over which a counter-attack would be launched. An attempt against the Federal guns would be suicidal. Lee was forced to admit the campaign was lost.

During the afternoon, he announced to his lieutenants his intention of withdrawing that night across the Potomac. At midnight Longstreet led the way across Boteler's Ford and formed a protective line on the south bank. Steadily through the night and early morning, the Confederate columns retreated into Virginia, covered by artillery.

On the afternoon of September 19th, Federals under Gen. Charles Griffin clashed with the Confederate rear guard. Lee, believing he was under heavy pursuit, sent A.P. Hill's division back to the Potomac. The massing Confederates pushed the Union troops back across the river near Shepherdstown on the 20th. His army now safe, Lee escaped to Virginia, battered but not beaten. McClellan went into camp around Sharpsburg. The Maryland Campaign was over.

Part of a series of articles titled A Savage Continual Thunder.

Previous: Harpers Ferry to South Mountain

Last updated: February 4, 2015