Last updated: January 14, 2026

Article

Anti-Suffrage in Massachusetts

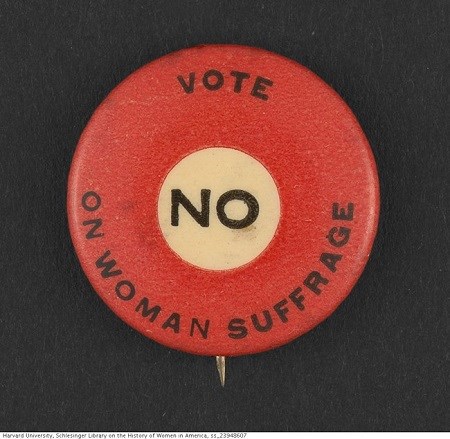

Courtesy of Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University.

The best work that a woman can do for the purifying of politics is by her influence over men, by the wise training of her children, by her intelligent, unselfish counsel to husband, brother, friend, by a thorough knowledge and discussion of the needs of her community…It is the opinion of many of us, that woman’s power is greater without the ballot…

-Clara T. Leonard, 1884[1]

The arguments and opinions voiced by those opposed to granting suffrage to women may appear incomprehensible today. Yet a significant number of women (and men) vehemently believed women’s suffrage would be detrimental to women, their families, and society as a whole. Though outnumbered by suffragists, women anti-suffragists (known as 'remonstrants'[2] in the early decades and sometimes shortened to 'antis') effectively slowed down the success of the suffrage movement by creating significant barriers at the state and national levels. Massachusetts in particular served as the home to one of the largest and longest-running anti-suffrage movements in the country. Its leaders came from old Boston families—wealthy, powerful, connected—and its influence extended far beyond the state borders.

Why did Massachusetts women actively work against what appears to be their own self-interest of gaining political representation? And, how did the anti-suffrage movement manifest itself in Massachusetts, the birthplace of the "American" ideals of liberty and equality?

Arguments Against Women's Suffrage

As suffragists dispersed arguments for women’s rights and suffrage to the American public in the 1800s, many began to consider the place of women in society. Anti-suffragists responded by reinforcing the Biblical argument of the "natural subordination of women" and the prevalent understanding of the "cult of true womanhood," which celebrated the ideals of submission, self-sacrifice, duty, piety, and domestic virtue.[3] Anti-suffrage arguments often derived from these ideals that argued women’s place remained firmly in the domestic sphere and warned of the potential consequences if women contradicted the natural order.

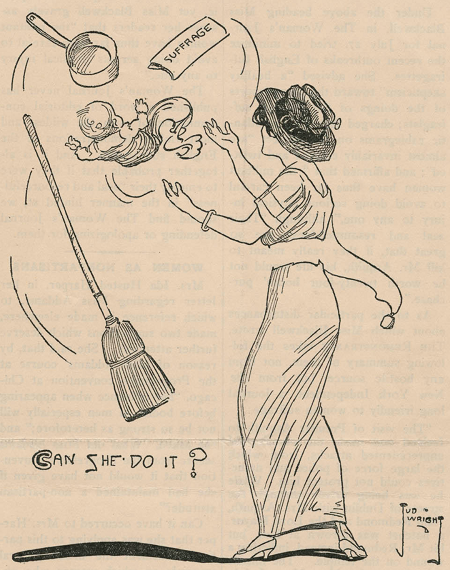

Jud Wright, Massachusetts Historical Society

Anti-suffragists embraced the dominant cultural norms of the time, the "separate spheres" of society. Women’s responsibility lay in the home, not in political affairs. Women anti-suffragists believed they could contribute to society most effectively by raising their children and positively influencing their male family members and friends.[4] The vote served as an unwanted burden for women and a necessary responsibility for men.[5] Representing their families and communities, men served and protected women by acting on women’s behalf when they voted. As remonstrant Clara T. Leonard noted, "What is good in a community for men, is good also for their wives and sisters, daughters and friends."[6]

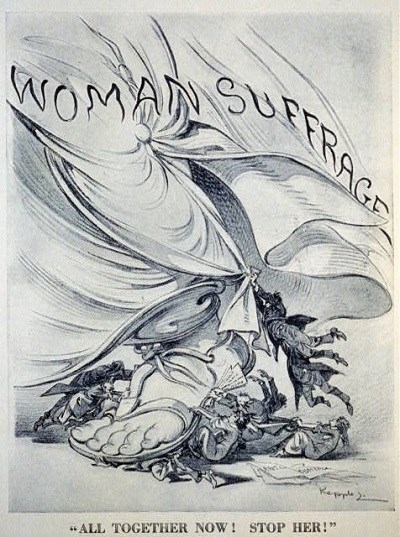

The prospect of women winning the right to vote brought fear of an impending shift in social order—a shift that would result in the destruction of the family, the upheaval of traditional roles and expectations, and the downfall of society. Antis warned, "One sex lives in public, in constant conflict with the world; the other sex must live chiefly in the private and domestic life, or the race will be without homes and generally die out."[7] Anti-suffragists contended that voting would radicalize women and make them unfeminine, and they feared female politicians would succumb to the inherent corruption of politics.

This concern of a shifting social order also brought fears that non-White, uneducated, non-U.S. born, and/or working class women would have as much access to participation in public affairs as upper-class, educated, privileged White women. While not always obviously stated, classist, nativist, and racist tones often underlined anti-suffrage arguments.

Many of these arguments remained critical to the anti-suffrage platform, with others becoming featured more prominently as the movement wore on. Noting the strides women made in the public sphere during the abolitionist movement and other social reform movements, anti-suffragists argued that women's rights had progressed so far that they no longer needed the vote.[8] Similarly, historian Susan Marshall noted how anti-suffragists believed "women’s traditional charitable and civic activities [could] effect more social reforms than…the ballot."[9]

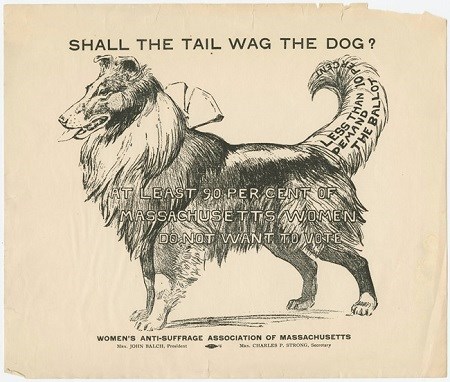

Finally, anti-suffragists argued that many women remained uninterested in voting. Pointing to low levels of women's voter registration and participation in school committee voting and other special elections, anti-suffragists suggested that suffragists were only a loud minority.[10]

These arguments, and others, expressed a general concern regarding the effect voting would have on women and society if women gained the right to vote.

Library of Congress

Committee of Remonstrants

In 1882, a group of Boston women congregated in one of the stately Boston brownstones to form the informal Committee of Remonstrants. This 13-women committee consisted of women from Boston’s upper-class, known as the "Boston Brahmins." They descended from Boston’s "founding families," and their husbands held wealthy and powerful positions, including state representatives, professors, doctors, lawyers, and businessmen.[11]

Organized in response to growing agitation for municipal suffrage, this committee met intermittently to write petitions that male representatives read to legislative committees. State senator George G. Crocker, whose wife Annie and daughter Sarah served as members of the committee, encouraged this, as "petitions in remonstrance were absolutely necessary, or they would wake up one fine morning and discover that the legislature had granted municipal suffrage to women."[12] In addition to petition-writing, the remonstrants circulated pamphlets and articles for newspapers, classifying their work as public education. In this way, remonstrants stayed within their appropriate sphere by allowing male allies to take on the more public roles.[13]

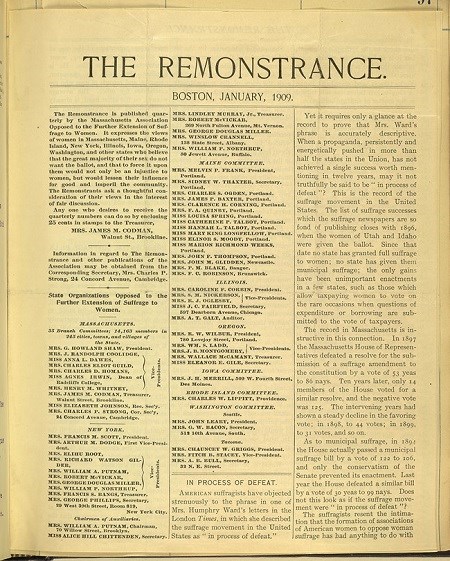

The Committee of Remonstrants founded the publication The Remonstrance in 1890 with members of the Man Suffrage Association (MSA), a short-lived organization that believed "the law of the division of labor and responsibility between the sexes excluded women from politics."[14] Published in Boston from 1890 to 1920, The Remonstrance began as a yearly newsletter before transitioning to a quarterly publication in 1907. The Remonstrance published information about legislative battles across the United States, evidence of societal failures in states where women had won the right to vote, articles explaining popular anti-suffrage arguments, and editorials from anti-suffrage men and women that reinforced traditional values and definitions of womanhood. Throughout its lifetime, this nationally distributed publication continuously responded to pro-suffrage rhetoric and advancements through an educational front.[15]

1895 Mock Referendum & Formation of MAOFESW

In 1895, the Massachusetts State Legislature passed the Wellman Bill, which granted a nonbinding state referendum regarding women’s municipal suffrage.[16] While pro and anti-suffragists believed the referendum was nothing more than a political stunt, both sides campaigned fiercely for their desired outcome. Remonstrants in particular argued for women not to vote: "We declare that the silence of our sex at the poles will not mean consent, but opposition or indifference."[17] In response to the referendum, The Committee of Remonstrants formally organized into the Massachusetts Association Opposed to the Further Extension of Suffrage to Women, known as MAOFESW, in May 1895. In organizing, MAOFESW declared:

The suffragists…continue to demand this undesirable and undesired privilege. While they remain active and aggressive, it is important that women opposed to female suffrage should also testify to their opinion.[18]

The transition to a formal, public organization marked a shift in the anti-suffrage movement, as women anti-suffragists now publicly acknowledged their participation in this counter-movement. However, MAOFESW members maintained their traditional role as educators, working with the Man Suffrage Association to send pamphlets and flyers. MSA members served the more public role, using their status as respected members of the community to solidify support.[19]

The results of the referendum swayed in favor of the anti-suffragists. Men voted down the referendum by a margin of two to one, and while women who voted overwhelmingly supported the measure, only a small number of those eligible participated in the referendum. Historian Susan Marshall recognizes how anti-suffragists "emphasized women’s lower voter turnout as proof of its argument that the majority [of women] was uninterested in the vote."[20]

Due to its success in blocking the referendum, MAOFESW soon became one of the largest and most influential anti-suffrage organizations in the United States. MAOFESW helped to found other state associations, directed referenda campaigns across the country, published the afore-mentioned publication The Remonstrance, and distributed thousands of leaflets and pamphlets. While both membership and leadership remained overwhelmingly female, MAOFESW still sought the support of male allies. In 1906, MAOFESW organized a "men’s advisory committee" to continue to advise on traditionally male responsibilities, including legal and financial assistance.[21]

Massachusetts Historical Society

Changes in the 20th Century & the 1915 Campaign

As suffragists embraced new tactics in the early 1900s, anti-suffragists also campaigned more actively. In 1901, MAOFESW began to recruit potential supporters of their cause, including "clubwomen, those with influential spouses, or the few professional women, mostly in education."[22] While Brookline and Cambridge served as the hubs of anti-suffrage leadership, antis tried to expand their reach to more diverse audiences, including geographic, religious, and racial and ethnic diversities. While Unitarian, Universalist, and Methodist clergies largely supported women’s suffrage, some Episcopalians and Roman Catholics expressed disapproval.[23]

Dissenters of women's suffrage could be found within any community; local Boston newspapers even mentioned the formation of an African American anti-suffrage organization in 1913.[24] Each group's reasonings for working against women’s suffrage differed. For example, while some African American women may have supported the notion of the traditional spheres for men and women, others expressed the inherent racism in the vote as their reason for objections, knowing that the vote would likely exclude them.

Expanding their influence also meant women anti-suffragists had to step more definitively into public roles, navigating the fine line between "public education" and public activism. Before 1902, anti-suffragists largely hired male speakers to appear before state legislatures. However, there became a growing need for women anti-suffragists to speak on their own behalf, so antis reluctantly responded to the call. They began appearing before state legislative hearings, and even began holding public meetings throughout Boston, including at Faneuil Hall.[25] In a speech before the Massachusetts State Legislative Committee, anti-suffragist Kate Gannett Wells expressed anti-suffragists' reluctance to speak:

The anti suffrage women are women so busy in their own homes, so occupied in charities and plans for the poor and ignorant, that they never have had time, more than that, they never have had the wish to come before the public, even in this Green Room. More than that, they do not think it is in woman’s place to argue or to refute statements in the arena of politics.[26]

Recognizing the irony of their public activism, anti-suffragists attempted to justify this shift by viewing it as a necessary obligation in order to prevent women’s full entrance into the political sphere. As an article in The Remonstrance noted, "Women who make their opposition to woman suffrage public do not do so because they crave publicity. It is not pleasure but duty which calls them to appear before legislative committees. They accept a present inconvenience to avert future harm."[27] Anti-suffragists also redefined the "home" by establishing anti-suffrage storefronts and offices as its natural extensions. This allowed women "…to enter a political campaign without leaving the women's 'proper' home sphere."[28]

Massachusetts Historical Society

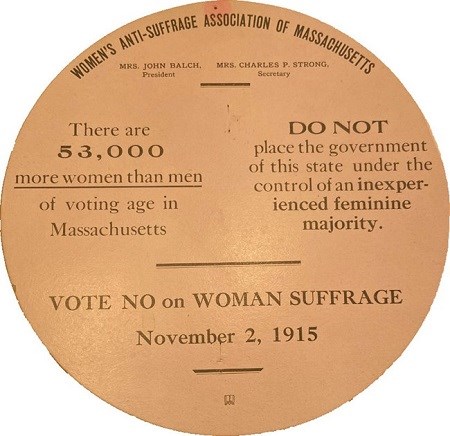

The Massachusetts anti-suffrage movement arguably reached its highest point during the 1915 State Referendum. This referendum questioned whether women should have voting rights in state elections. As suffragists increased their publicity with public rallies, mass meetings, and campaigns, so did anti-suffragists. MAOFESW changed its name to the Women’s Anti-Suffrage Association of Massachusetts for the campaign, and it continued to send pamphlets and flyers, as well as host a variety of public events and meetings. Now grown to over 35,000 members, its efforts reached the entirety of the state.[29]

Although suffragists and anti-suffragists frequently combatted each other in writing and in the State House, one of their largest public confrontations occurred during the 1915 Suffrage Victory Parade. To counter the thousands of suffragists marching in the streets of Boston, anti-suffragists “[decorated] houses along the parade route with red bunting,” banners, and posters. Anti-suffragists sold red roses, the symbol of anti-suffrage, while suffragists sold yellow camelias and roses, yellow being a color associated with the women’s suffrage movement. Newspapers remarked on the clashing visions of yellow and red among the crowd, as parade watchers demonstrated support for their side. Finally, antis held a silent counter-protest by releasing red balloons on Huntington Avenue by Copley Square.[30]

Massachusetts anti-suffragists claimed victory yet again in 1915. Despite decades of work by suffragists, the outcome remained largely the same as the earlier 1895 referendum, with men opposing suffrage by a two to one margin.[31] Massachusetts men had not yet been fully convinced of the need (and benefit) of women’s suffrage.

Library of Congress

While Massachusetts anti-suffragists effectively stemmed the progress of the state and national suffrage movement for decades, they could not stop the eventual victory of women’s suffrage. Although successful in 1915, Massachusetts anti-suffragists soon saw a weakening fervor for their cause, likely due to changing social norms.[32] Their work did not prevent the ratification of the 19th Amendment in August 1920. Resigned to their new responsibility as voters, many former anti-suffragists surprisingly registered to vote. One former anti-suffragist noted on Election Day 1920,

I am casting my first vote. I didn't believe in suffrage, but it's come. I'm simply doing my political duty, as I did my political duty when I fought against the ballot.[33]

Footnotes:

[1] Clara T. Leonard, "Letter from Mrs. Clara T. Leonard, In Opposition to Woman Suffrage," Massachusetts Association Opposed to the Further Extension of Suffrage to Women, 1884. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=bc.ark:/13960/t7xm3g60x&view=1up&seq=1

[2] The term “remonstrant” derives from the word “remonstrance,” meaning “protest.” Remonstrants protested the ongoing movement to enfranchise women.

[3] Susan Marshall, Splintered Sisterhood: Gender and Class in the Campaign against Woman Suffrage (Madison, WI: The University of Wisconsin Press, 1997), 19.

[4] Leonard, "Letter from Mrs. Clara T. Leonard, In Opposition to Woman Suffrage;" Louise Stevenson, “Women Anti-Suffragists in the 1915 Massachusetts Campaign,” The New England Quarterly Vol. 52, no. 1 (March 1979), 85.

[5] Elizabeth V. Burt, “The ideology, rhetoric, and organizational structure of a countermovement publication: The Remonstrance, 1890-1920,” Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 75, no. 1 (1998): 74-75; Marshall, Splintered Sisterhood, 98.

[6] Leonard, "Letter from Mrs. Clara T. Leonard, In Opposition to Woman Suffrage.”

[7] Leonard, "Letter from Mrs. Clara T. Leonard, In Opposition to Woman Suffrage.”

[8] Leonard, "Letter from Mrs. Clara T. Leonard, In Opposition to Woman Suffrage;” Marshall, Splintered Sisterhood, 99-100.

[9] Marshall, Splintered Sisterhood, 102.

[10] Marshall, Splintered Sisterhood, 25.

[11] Members included de facto president Mrs. Charles D. Homans (Eliza), Mrs. George G. Crocker (Annie), Mrs. J. Randolph Coolidge (Julia), Mrs. Oliver W. Peabody, Mrs. G. Howland Shaw (Cora), Mrs. Robert C. Winthrop (Adele), Mrs. William B. Swett (Susan), Mrs. James C. Hooker (Elizabeth), Mrs. Henry O. Houghton (Nancy), and Mrs. James C. Fisk (Mary). Marshall, Splintered Sisterhood, 23, 28-31.

[12] Marshall, Splintered Sisterhood, 24, 59.

[13] Marshall, Splintered Sisterhood; Stevenson, “Women Anti-Suffragists in the 1915 Massachusetts Campaign,” 81-82.

[14] James J. Kenneally, “Woman Suffrage and the Massachusetts ‘Referendum’ of 1895,” The Historian 30, no. 4 (1968): 617-633.

[15] Burt, “The ideology, rhetoric, and organizational structure of a countermovement publication;” Marshall, Splintered Sisterhood, 24-25.

[16] Kenneally, “Woman Suffrage and the Massachusetts ‘Referendum’ of 1895,” 620; Marshall, Splintered Sisterhood, 60.

[17] Kenneally, “Woman Suffrage and the Massachusetts ‘Referendum’ of 1895,” 624.

[18] Massachusetts Association Opposed to the Further Extension of Suffrage to Women, “Leaflets” Boston, 1884-1904, 60 nos. [DYW5.9M38 in card catalog, not online], Boston Athenaeum.

[19] Kenneally, “Woman Suffrage and the Massachusetts ‘Referendum’ of 1895,”624; Marshall, Splintered Sisterhood, 65.

[20] Burt, “The ideology, rhetoric, and organizational structure of a countermovement publication,” 76; Marshall, Splintered Sisterhood, 24.

[21] Marshall, Splintered Sisterhood, 15, 71.

[22] Marshall, Splintered Sisterhood, 166.

[23] Marshall, Splintered Sisterhood, 170-175.

[24] "Colored Women Organize Association and Will be Represented at State House Tomorrow," The Boston Globe, February 26, 1913; "Opposes Votes for Women," The Boston Globe, February 28, 1913.

[25] "'Antis' Attack Suffrage in Faneuil Hall," The Boston Herald, April 04, 1914.

[26] Kate Gannett Wells, “An Argument against Woman Suffrage; delivered before a special legislative committee,” Massachusetts Association Opposed to the Further Extension of Suffrage to Women, c. 1900s. https://curiosity.lib.harvard.edu/women-working-1800-1930/catalog/45-990012575990203941

[27] Burt, “The ideology, rhetoric, and organizational structure of a countermovement publication,” 74.

[28] Stevenson, “Women Anti-Suffragists in the 1915 Massachusetts Campaign,” 81-82.

[29] Marshall, Splintered Sisterhood, 172, 195.

[30] Marshall, Splintered Sisterhood, 193; Stevenson, “Women Anti-Suffragists in the 1915 Massachusetts Campaign,” 83-84; "200,000 See the Paraders," The Boston Globe, October 17, 1915; "Suffragists Promise a Record Turnout Today," The Boston Globe, October 16, 1915.

[31] Robert S. Grandfield, “The Massachusetts Suffrage Referendum of 1915.” Historical Journal of Massachusetts 7, no. 1 (1979): 54; Marshall, Splintered Sisterhood, 75.

[32] Burt, “The ideology, rhetoric, and organizational structure of a countermovement publication,” 79-80; Stevenson, “Women Anti-Suffragists in the 1915 Massachusetts Campaign,” 93.

[33] "Women Take the Ballot Seriously," The Boston Globe, September 08, 1920.