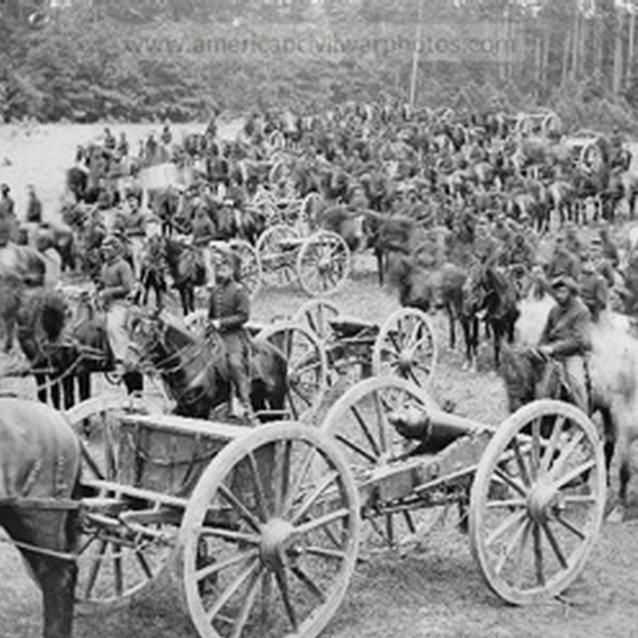

Animals played important roles in the Civil War for a variety of reasons. Horses, mules, and oxen were used for transportation. They pulled supply wagons, ambulances, artillery pieces, and anything else that needed to be moved. Officers directed battle from horseback, messengers on horses made communication more efficient, and cavalrymen lived and fought in the saddle. Acquiring, feeding, and caring for these animals was a massive, but necessary undertaking. The men often developed close bonds to particular horses and mules and were devastated when they were killed.

"A horse for military service is as much a military supply as a barrel of gunpowder or a shotgun or rifle." Union Quartermaster Montgomery C. Meigs

Transportation, Food, Mascots

Library of Congress

Army regulations made no provisions for mascots, but many units adopted them as symbols of loyalty and devotion. Most mascots were dogs, but cats, pigs, and goats also served in that honorable position for units on both sides. One of the most famous mascots of the war was "Old Abe," a bald eagle, who flew over the 8th Wisconsin Volunteers at 36 different battles. He survived the war and lived in the Wisconsin capitol building until he was killed in a fire at the age of 44.

Other mascots included gamecocks, donkeys, and a camel named Douglas, who carried supplies for the 43rd Mississippi. There were also several regiments who kept bears as pets. The 26th Wisconsin, honoring the "Badger State," kept one of those ferocious animals as their mascot.

Not all animals were lucky enough to be treated as heroic mascots or loyal mounts. Many animals, especially cattle, were used as an important food source for both armies. Columns of troops and wagon trains were often followed by huge herds of "beef on the hoof." Chickens, pigs, and cattle were slaughtered and served in camps. Millions more were processed in factories and salted for shipment to hungry soldiers. When the armies didn't have enough, local animals served as meals. Sometimes buying, sometimes just taking, soldiers used private farms and barns to fill their bellies, often decimating local stores and herds.

Feeding an Army

Library of Congress

Napoleon once said, "An army marches on its stomach," meaning to have an effective army, the men must be fed. While corn meal, hardtack, potatoes, beans, salt, sugar, and coffee were all part of a soldier's diet, meat remained the most important source of protein for men marching, working, and fighting on long campaigns. Chickens, hogs, and cattle were all transported with the armies on the march, with larger quantities slaughtered by civilian contractors and shipped to the front. Second only to ammunition, quartermasters worked tirelessly to keep soldiers supplied with food.

During the Maryland Campaign, in fields around Frederick, army butchers took cattle from the large herds moving with the wagon trains and distributed the meat to the men along with salt pork in barrels. When the men felt that these rations were not enough, they sought bigger and better meals on their own. Sometimes they hunted deer and fished in rivers. Packages from relatives and friends also often contained some kind of food. Sutlers, private sellers, also mingled with men in the camps, selling them what the army could not provide. All too often, though, men on the march took what they needed from farms and villages. Confiscating animals and stripping fields of crops helped feed the armies, but depleted the supplies for civilians, often leading to poverty and famine.

The Mules of War

Library of Congress

Mules powered C&O Canal boats. Teams of four animals, two pulling while two rested in the boat mule barn, pulled the boats laden with up to 130 tons of coal or other cargo. At its peak, over 500 boats traveled the canal, bringing the total number of mules on the 184.5 mile towpath to over 2,000.

During the Civil War mules also pulled wagons and guns in the Confederate and the Union supply trains. During the Maryland Campaign the Union Army used over 10,000 mules to help transport their supplies. During the war, canal workers feared their mules may be confiscated by troops or raiders, leaving the canal boats without their source of power.

As Confederate troops passed through the Antietam area, canal worker Jacob McGraw noted, "Stragglers were running around robbing the houses of people who'd gone away, and they got in my house and just took everything... Besides, they took five mules of mine out of a field where I kept `em. Them were mules that did my towing on the canal."

Part of a series of articles titled The Burden of Beasts.

Next: Fast and Flexible

Tags

Last updated: February 3, 2015