Last updated: July 6, 2020

Article

Alexander Pearson: An Early Pilot of Aviation History

NPS Photo

By Fort Vancouver National Historic Site Volunteer-in-Parks Dr. Robert Staab

Early Years

Alexander Pearson, Jr., was born November 12, 1895, in Sterling, Kansas. At the beginning of World War I, he studied at the University of Oregon. During his senior year, he enlisted into the US Army, and attended Reserve Officer’s Training Camp at the Presidio, San Francisco. He was commissioned as an infantry officer in the Reserve Corps on May13, 1917. He wanted to transfer to the Aviation Section of the Signal Corps, but was denied, so Pearson resigned his commission and enlisted for ground school work in the Signal Corps on June 27, 1917.

Re-examined for flying school, he entered the Air Service in Seattle on November 23, 1917. Pearson was a cadet at the University of California at Berkeley, Camp Dick, Dallas, and Rockwell Field, San Diego. He was commissioned and ordered into active duty as a 2nd Lieutenant at Rockwell Field on July 29, 1918. He was ordered to the US Air Service Armorer School at Wright Field, Dayton, Ohio, on August 9, 1918 and attended school until September 10, 1918.

During and after World War I, he was a flying instructor at various fields: Payne Field, West Point, Mississippi; Carlstrom Field, Arcadia, Florida; Scott Field, Belleville, Illinois. For his last assignment, he was stationed in New York, waiting to go overseas, but the war ended before he could be deployed.

At the end of the war in 1918, he returned to the University of Oregon to complete his degree. He later graduated with a Bachelor of Science degree.

NPS Photo

Flying Exploits: 1919-1920

After the war, most squadron members were separated from the Air Service and returned to civilian life. A small cadre of servicemen, including Pearson, remained on duty, and found time to participate in record-setting aviation competitions.

On October 8, 1919, Lt. Pearson, with his mechanic, Loyal Atkinson of Oregon, took off from Roosevelt Field (near Mineola, New York) on Long Island in the first transcontinental air race. The race was a round trip from New York to Crissy Field (Presidio), San Francisco. A pilot had to be able to fly at least 100 mph. Originally, 100 entrants started the race: fifty started from San Francisco, and fifty started from New York. The route included the following cities and towns across the United States: Mineola, Binghamton, Rochester, and Buffalo, New York; Cleveland and Bryan, Ohio; Chicago and Rock Island, Illinois; De Moines, Iowa; Omaha and St. Paul, (on the return trip Sidney and North Platt) Nebraska; Cheyenne, Wolcott, and Green River, Wyoming; Salt Lake City and Saludro, Utah; Battle Mountain and Reno, Nevada, and Sacramento and San Francisco, California.

Pilots in the race flew DeHaviland-4 aircraft. Entrance in the race was confined to Army pilots only, who were recommended by their commanding officers. The race competition was broken down according to the following categories:

Time Competition – Shortest Time: the flyer, who flew fastest, irrespective of stops. Flying time was the winner.

Speed Competition—One making the fastest flying time.

Handicap Competition—One making the fastest flying time taking the normal speed of the plane into consideration.

Three awards were given out: Lieutenant B.W. Maynard won the total length of the time consumed in making the round trip. Lieutenant J.O. Donaldson was awarded first prize upon test reliability. Lieutenant Pearson won on the “actual flying time consumed in making the flight.” It was a world record at that time. His comments about the race, “Yes, I got there and back!”

Pearson won points for the Speed and Handicap competitions, crossing the continent twice at 40 hours, 14 minutes, and 8 seconds. His prizes for his accomplishments for the race were a Thermos bottle from the Cleveland Flying Club and a leather flying suit from Brooks Brothers. He also received $825 of liberty bonds, but they were not given out at this time, only trophies and prizes.

After the race, in Pearson’s report to the Director of Air Services dated November 3, 1919, he stated that the weather, especially rain, was damaging to the propellers and had to replace two props in his round trip. He also burned out a bearing rod on the motor and had to replace it with Martin Bomber engine half way between Sidney and North Platt, Nebraska. He used a Rand McNally Railroad map as his guide. He flew “practically airline or compass routes.” He complained about the “local weather information, which was lacking, and markings on maps for local airfields, but had little trouble landing and taking off. There was good service and assistance at the various landing sites.”

In the summer of 1919, Pearson was transferred to Scott Field, in southern Illinois. There he was assigned to fly ahead of the Army’s transcontinental Truck Convoy, scouting their route. This truck convoy, intended to test the army’s ability to travel across the continent, included a young officer named Dwight D. Eisenhower, who later served as President of the United States.

Crash in Mexico, February 1921

From January 6, 1919, to November 2, 1922, Pearson was stationed with the 12th Observation Squadron flying out of Douglas, Arizona. First, he was an adjutant, then he was commissioned Regular Army on July 1, 1920.

His duties at Douglas included flying reconnaissance along the U.S.-Mexico border. Post World War I, U.S. Army Border Air Patrol used Air Service squadrons to fly along the border between the United States and Mexico, searching for bandits and cattle rustlers. The pilots reported what they saw from the air to the nearest cavalry post.

The patrol bases were hurriedly created. One of the young lieutenants, who flew from Marfa Field in Texas in the summer of 1919 remembered the flying field as a pasture at the eastern edge of town. Its five hangars were made from canvas. A double row of ten or twelve tents served as quarters for officers and enlisted men, and sheltered flight headquarters and supply. The lieutenant, Stacy C. Hinkle, recalled his tour of duty on the border as “a life of hardship, possible death, starvation pay, and a lonely life without social contacts, in hot, barren desert wastes, tortured by sun, wind, and sand.” The boredom was as bad as the physical hardship and discomfort. Even so, Hinkle thought that the airmen were better off than the poor fellows at cavalry outposts up and down the border.

Preparations for the Flight from Florida to California

On December 28, 1920, Pearson began preparation for a transcontinental flight from Pablo Beach, near Jacksonville, Florida, to Rockwell Field, in San Diego, California. The trip would be made in a De Havilland 4-B plane (a new motor was installed and the plane recently painted), with extra gas tanks (the extra gas tanks held 82 and half gallons) and oil tanks.

The flight was to take place on February 22, 1921. It was to include two stops: one at Ellington Field, Houston, 804 miles away, and one at El Paso (Fort Bliss), 660 miles, and finishing at Rockwell Field, a total distance of 2,079 miles, establishing a new transcontinental record.

Pearson was quoted as saying, “I am sure that I can make the trip in 24 hours and in probably less time.… I am counting on two stops between the two coasts. On the trip I will land in Houston and then El Paso, then on to San Diego. The flight from Pablo Beach to Houston can be made in eight hours, from Houston to El Paso in less than eight hours, and El Paso to San Diego in the same time. I need to average 95 mph to cover the distance in 24 hours. … I expect to do better than that.”

Lieutenant W.B. Coney was to accompany him from Florida to San Diego.

A Breakdown and a Forced Landing

In a memo written by Pearson on February 19, 1921, to the Chief of Air Service, Washington DC, regarding the transcontinental flight, he noted the changes to the gas tanks, oil tanks, and water for cooling the motor. He also described the changes in the cockpit moving from the front seat to back seat with all necessary controls, and placing the gas tanks in the front. Additional changes were made to the ignition and rigging. A new Lincoln Liberty motor was installed first, then after the malfunctioning outside of Columbus, New Mexico, they installed another, a Ford Liberty motor.

First, though, Pearson had to get from his duty station in Douglas, Arizona, to Florida, where the transcontinental flight would start. He took off from Camp Harry J. Jones in Douglas, towards Florida on Tuesday, February 7, at 10:30 am. Past Columbus, New Mexico, he developed engine trouble and forced him to land about 13 miles east of Columbus, on the US-Mexico border. Army officials rushed a new engine from Douglas, and thought the trouble was fixed. On February 8th, in the afternoon, he was able to fly to Fort Bliss, El Paso, to spend the night.

The next day he left Fort Bliss at 10:45 am, en route to Pablo Beach, stopping over at San Antonio, along the way. Flying at 4,000 feet, his flight path was 60 miles from any railroad lines. He skirted the Big Bend territory, a very desolate area, and far from any modes of communication.

After two and half hours of flying, he noticed the motor vibrating slightly, his oil pressure dropped significantly; he then began to look for a landing spot. By this time, Pearson was south of Sanderson, Texas, flying over the Rio Grande River, making large spirals to loose altitude, seeing if he could regain his oil pressure. Soon the engine bearing burned out completely and began to disintegrate. It threw a rod, blowing out bearings, and he lost all power. His crankshaft stopped. He was 8,600 feet altitude. Over the river, he started spiraling downward.

Despite seeing the Rio Grande River and trying to land in the United States, he could not find a suitable landing site near the river. The area was filled with tall cacti and mesquite brush, but few rocks. He eventually landed about five miles south of the river, where he claims he made a perfect landing in a small space; one of the plane’s tires exploded, and the brush bordering the open space tore the tip of one of his wings. But the brush did act as a brake for his plane, because the plane was still intact; however, the engine was ruined. He still had oil in the engine, but it was the major reason for his crash.

He landed, probably 100 miles southwest of Sanderson, Texas, and 7 miles west of Reagan Canyon, near Boquillas, Mexico, 250 miles southeast of El Paso. He crashed three hours after he left Fort Bliss.

He had landed about 1:30 pm. He waited until the engine water cooled, so he would have water to drink. He did not know where he had landed, but it was in a wild desert country, without much vegetation. He started in the wrong direction, being a bit confused after his spiraled landing and the direction of the river. As soon as he landed he headed south and hiked the whole day and Thursday night. He hiked all day Friday and Friday night with only water from the plane’s radiator.

He did not see any human or animal life. Soon, he got his directions correct. He wandered in search of a town or settlement, surviving dust storms, and drinking only radiator water. He went up and down very rocky terrain, paralleling the Rio Grande River. Water from the radiator provided some relief, but fresh water was nonexistent.

The Search for Pearson

A telegram, dated February 15, 1921, five days after the crash, indicates the efforts being waged in his search. “Search being continued and airplanes being concentrated at Sanderson and Marfa, Texas. Major Leo J. Heffernan was ordered to Sanderson to assumed charge of the search.”

There were doubts that he survived the crash, but the Army Air Service believed that he was alive and had survived the crash. Sixty-five planes were involved in the search from Kelly Air Field in San Antonio, Fort Bliss, Del Rio, Sanderson, McAllen, Marfa, and from the Border Patrol.

Newspaper headlines feared that he had died in the crash, with one stating “AVIATOR BURNED TO DEATH, FORT BLISS OFFICIERS FEAR AS FIVE-DAY SEARCH ENDS.”

A giant Caproni photographic plane, carrying sufficient gasoline for a nine hour flight, with four observers, plus the two pilots was used in the search. Flying at 10,000 feet they scanned the Pecos River Valley. This plane was capable of photographing 100 square miles. Its enlarged photographs were processed and studied at Kelly Air Field, in San Antonio.

The search planes were ordered to fly as close to the ground as they could, with powerful binoculars. They flew in pairs and dropped flyers from the air, stating “WAR DEPARTMENT IMPORTANT NOTICE– Did you see an Airplane on Thursday February 10th, 1:00 – 3:00 pm? If you did, wave…point in the direction of the plane…Telephone all information to Sanderson, Texas.” In addition to the air search, cavalry units, cowboys, and rangers were enlisted to do a ground search in the Crockett County area, west of Sanderson.

Headlines stated the obvious: “Aviators Find No Trace of Pearson in the Desert, Desert Holds Mystery of Pearson’s Fate.”

In the midst of the search, another fear arose: that he had flown into Mexico and was being held by Mexican authorities. This was not uncommon for pilots to lose their directions, crash, and end up in Mexico. Headlines talked of his heroism in somber-yet-glowing terms.

NPS Photo

Help From a Skunk

About 2 to 3 am in the morning on Saturday, Februrary 11, 1921, Pearson smelled the violent odor of a “polecat” (skunk), and heard the croaking of bull frogs. He knew water was near; it was the Rio Grande River. It was five o’clock in the morning, when he reached the banks of the river.

He tried to drink the water from the river; however, he became ill and vomited. He rested until daylight. He noted that the river's current was flowing left to right, which indicated that he was in Mexico. He walked downstream and found a raft. Some sources say that this raft was made from abandoned wash tubs, others say that he made it from logs and branches he found at the river’s edge. Whatever the case, using an old broom handle and some tin, he made a paddle, which provided steerage through rapids and rocks. He also found a tin pan to boil water.

He drifted until 9 am Sunday morning, when he spotted two trappers, who told him he was in Reagan Canyon of the Big Bend country. These men – beaver trappers— Amos and Roy Rutledge, gave him “bread, gravy and coffee.” This was his first food in three days, and they insisted that he eat slowly. Then he accompanied them to their camp and stayed Sunday and Monday and rested. On Tuesday morning, they gave him a burro, and with Amos, they rode downstream 4-5 miles, to the old Candelaria wax factory. Here they exchanged burros for horses and they headed towards Sanderson. The ride out of Reagan Canyon was very rocky and perilous for the horses. Over very rough terrain, they rode to Young’s Ranch, where they stayed Tuesday night. Then they went on to Elder’s ranch, 15 miles from Sanderson. Amos returned with his horses back to Young’s ranch. The next morning two of the Elder’s boys took him to Sanderson, arriving that evening.

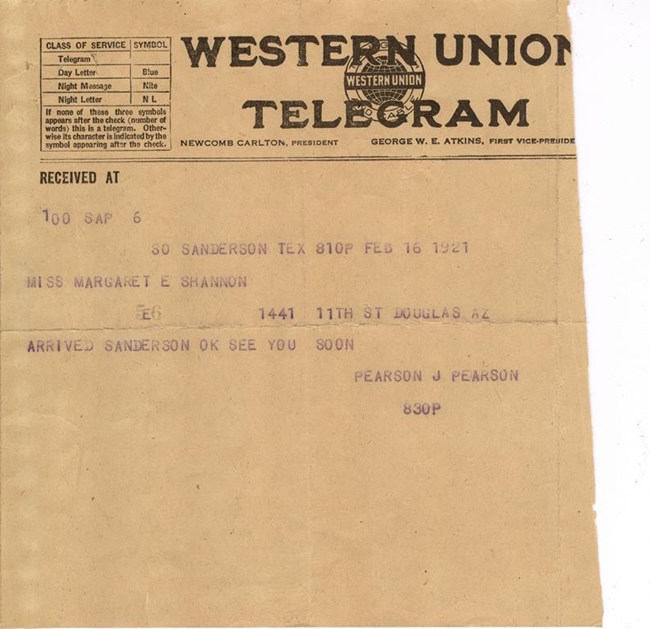

Arrival in Sanderson

“Lt. Woodruff was the first one in Sanderson that I knew. His jaw dropped about a foot, when he saw sight of me, I think,” Pearson was quoted in one newspaper.

When he arrived in Sanderson, Pearson said he was too tired and excited to immediately relate much of his experiences. “I have been through considerable since I left El Paso last Thursday morning,” he said. “Please don’t ask me about it tonight. Just send these messages and I’ll retell you all about it when I get some sleep.”

He sent a telegram immediately to his fiancé, Margaret Shannon, in Douglas, on February 16 (15), 1921. He also sent messages to his parents, and to Fort Bliss. He then rested in a hotel, with Army guards posted to protect his privacy.

A poem posted in local daily newspaper summarizes his ordeal well:

“Lt. Pearson skyward went,

To cross the well-known continent,

He landed in Texas scrub,

Far from companionship and grub,

Though proud to fly, he was no fool,

And gladly came home on a mule.”

Despite his ordeal, Pearson claimed “to have reached Sanderson in better condition physically than he was when he left Douglas on February 7.” He flew off for Douglas the next day.

His plane in Mexico was eventually found and repaired under the supervision then-Lieutenant Jimmy Doolittle, who would later become famous for his exploits during World War II. After two weeks of repairs and building a runway through brush and rocks, Doolittle took off and flew the craft back to San Antonio for further refurbishing the following May.

NPS Photo

Survey of the Grand Canyon

On May 26, 1921, orders were sent to Pearson to begin to prepare for the study of the Grand Canyon with the end goal of establishing an airline passenger and mail service through the canyon.

“The possibility of opening up an aerial passenger service through the Grand Canyon is being planned by the War Department…. Lt. Alexander Pearson, transcontinental flyer, has been ordered to see if he can locate landing fields and then make an aerial observation trip to ascertain air conditions at various times a day and note emergency landing fields.”

The survey was made at the insistence of the Department of the Interior to ascertain the air conditions and possible landing places between Union Pacific Railroad in Utah and the Santa Fe Railroad in Arizona in preparation for mail and passenger services between the two lines.

Pearson was showered with tales of the dangers in the Canyon with its temperamental clouds, storms, and air currents; as he expressed it, he was “almost scared to death of the job that had been assigned to him.”

At this time, Pearson was stationed at Nogales, Arizona. He was on Forest Duty when he received his orders regarding the Grand Canyon. He was accompanied by Sergeant Arthur Juengling, “who he could not get along without and called him a ‘mechanician’.”

He left Nogales on May 31st for the Grand Canyon, making stops at Phoenix, Prescott, Ash Fork, and Williams. From various sources noted, it appears one of Pearson’s duties was to determine the viability of landing fields at various towns in Arizona. Several times he wrote in his reports about the possibility and the costs of constructing landing fields in the areas where he stopped.

Pearson arrived on June 4th at Grand Canyon National Park and the day was spent in conference with the national park's superintendent. They drove around the park looking for suitable landing sites. No site closer than eleven miles was found, due to the dense forest surrounding the park. Fairly good emergency fields were found to the north, west and east of Anita, today a ghost town on the railroad line between Williams and the Grand Canyon. His recommendations for a landing site is around Anita because of the railroad, and the transportation via the railroad and cars to the park.

He traveled on June 5th again to the park in the company of the chief ranger to look over the plateau (possibly on the canyon's South Rim), which was determined to be fairly level, rough, and full of small rolls and hollows. In his notes, Pearson described the costs of leveling and building a suitable field on the plateau.

On June 6th, he flew back to Nogales. On June 9th, he flew from Nogales back to Williams, which was to be used as his base for the Grand Canyon survey. Williams’ air field contained gas and oil products (Mobile-B). No other site was as good between Williams and the park. He left Nogales at 4:10 pm and arrived in Williams at 7:15 pm, and reported a good flying time and weather. Total mileage was 276 miles in his DeHaviland-4.

Flying his DH-4 from Williams, Lieutenant Pearson and Sergent Juengling flew in and around the Grand Canyon for two hours and forty minutes on June 10th, inspecting the Canyon, Cataract Canyon, and west as far as Seligman (West of Williams). At times he flew over Flagstaff, circled around the San Francisco Peaks, then flew north over the Grand Canyon. Afterwards, they flew back to Williams. Lumbermen working in the nearby forest remember seeing his plane.

Pearson reported that the “Air was quite calm except for the ‘heat swells.’ Slight east wind blowing and it was very warm. It was smooth over and in the canyon, except for the strip along the canyon walls. Here very rough region of ¼ and ½ mile along the walls; it was caused by the uprising currents of air heated by the canyon walls.”

He went on to say, “I flew over the canyon for one hour experiencing no difficulty, except motor heating, when I was down in the canyon, due to the hot air conditions there.”

On crossing the Grand Canyon, he noted “… pay no attention at all of the talk we have heard about cross currents, air pockets, etc. making the air above it impossible to navigate. I flew around at various altitudes above and below the rim as I pleased.”

Pearson flew into the canyon, landed and took off again at an altitude of 9,000 feet. (The north rim of the Canyon is 8,297 feet.) Afterwards, he said “… he believed this was the first time either of these feats have been accomplished.”

On June 11th, Pearson left Williams 8:25 am, flying by way of Flagstaff, San Francisco Peaks, Little Colorado River, Painted Deserts, Marble Canyon, and Kaibab Plateau, noting, “Land after the Peaks is very rough sandy desert that would surely cause a crash.” The Kaibab Plateau is a high rolling plateau heavily covered in timber. He discovered a unique spot in the plateau called “Big Park,” which is bare, approximately ½ mile wide and 5-6 miles long, with a north-south alignment. He landed here and took off without any issues. He landed at 10:20 am. He reported that “It is a good field, with elevations 8,800 ft., no preparation for field necessary. Took off at 10:35 am without difficulty, flew around the Grand Canyon.”

“There was a slight west wind. I crossed the canyon at 4,000 feet (above the rim), and then crossed back at 1,000 feet (above the rim). Air currents were fairly smooth, so I descended to 3,500 feet below the south rim and 4,500 feet below the north rim.” He descended 200 feet into the lower and narrower portion known as the gorge. “No difficulty was experienced except that the motor became very hot due to the hot air in the bottom of the Grand Canyon.”

After landing back at Williams, Pearson telegrammed Margaret Shannon about that day saying “…nothing new today, landing over the north rim at 9,000 feet altitude. Sorry you can’t come to see the canyon. Visit Prescott tomorrow. Fine luck so far. Best regards, Pearson.”

He then flew to Prescott to inspect local landing fields. Again, as part of his assignment, he was visiting all possible landing fields between the border (Nogales) and the Grand Canyon.

While in Prescott, a newspaper reporter from the Prescott Journal-Miner interviewed Pearson about his flights over the Grand Canyon. Pearson was “surprised how easy it was to land and take off at 9,000 feet. Before this flight, the highest he had attempted was in Rawlings, Wyoming at 6,750 feet.”

Between June 13th and 17th, Pearson and Juengling flew several times in and around the Canyon. Pearson continued to study air currents in and over the canyon and locate landing fields. Up until this study, it was deemed impossible “to fly across the canyon because of tempestuous air currents tumbling into and out of the canyon. To fly through the canyon, below its rim, for the same reasons plus the danger of being dashed against the upstanding pillars and peaks of the canyon. It was impossible to take off from a landing of 9,000 feet above sea level because of the rarity of the atmosphere.” He proved all was possible.

On June 17th, “In spite of the fact that the upper part of the Grand Canyon is 13 miles from rim to rim and lower part at the gorge is eight miles wide …I felt cramped for room when I was descending in to the chasm. I seemed every moment to be flying right slap into some cliff. This was an illusion, of course, due to the unusual situation of an airplane seemingly flying below ground.”

Upon the completion of his assignment, Pearson wrote a report on his Grand Canyon assignment, sent on June 24, 1921, to Air Officer, Eight Corps Area, Fort Sam Houston, Texas. In his final report, he reported that “total flights of 14, flying time of 22 hours, 5 minutes, were made. From June 9th to June 22nd." In the four days that Pearson flew into the Grand Canyon, he used 430 gallons of gas, and 50 gallons of oil. “I believe that commercial flying across the Grand Canyon and its vicinity is entirely feasible and practicable," he wrote. Pearson advised that a plane must be able to climb at least at a rate of 400 feet per minute at 7,000 feet and a 17,000 foot coiling be required of the operating company in order to assure the safety of the passengers. No plane should fly less than 11,500 above sea level over the canyon. He further described the types of landing fields and their locations that need to be built around the canyon. Finally, he also recommended that air fields be at least two miles from the rim due to turbulence caused by air currents near the canyon.

He also suggested “truck cars” might be used to haul passengers from Anita to the Grand Canyon and “Auto Stages” could be used to connect Big Park with the railroad at Marysvale, Utah. “I believe that commercial flying in this vicinity has great possibilities both as for ferrying and sightseeing propositions.”

The technical material related to this portion of his life was taken from the report that was written on June 24, 1921, to the Air Officer, Eight Corps Area, Fort Sam Houston.

NPS Photo

Wedding, December 26, 1921

Alexander Pearson married Margaret E. Shannon on December 26, 1921 at the home of her parents in Douglas, Arizona. She was a bookkeeper at the Douglas Investment Co. and was the granddaughter of the former governor of New Mexico. Pearson was stationed at Camp Jones for several months in Douglas, where they met. The ceremony took place for a few close friends and family. They were to honeymoon for three weeks at the Grand Canyon, via an automobile, but snow and bad roads force them to take the train. They made their home in El Paso, near Fort Bliss, where Pearson was to be stationed.

NPS Photo

Transcontinental Trips and Crashes, 1922

On July 2, 1922, Pearson flew from Fort Bliss to Portland, Oregon. He flew in one day in an effort to see how fast an Army plane could fly to the West Coast to defend against a theoretical military attack. Flying a DH-4, he left Fort Bliss, at 4:15 am. He flew from El Paso to Douglas, Riverside, and then to Sacramento. He landed at Sacramento at 3:10 pm. He spent the night in Sacramento to visit with some of the “boys.” The next day, he set out for Portland, flying between 7,000- 8,000 feet. During the flight, forest fires in the Pacific Northwest caused low visibility. Over Eugene, Pearson and his co-pilot, Sargent E. F. Nendell of Woodburn, Oregon, encountered heavy smoke. When they arrived over Lebanon, Oregon, they had to fly at an altitude of about 200 feet and follow the railroad tracks to Portland. Before they landed at Lieutenant V. U. Ayres Field in Portland, a few cows had to be driven off the field. They landed at 8:58 am, two minutes ahead of schedule. Total flying time from El Paso to Portland was 29 hours, 1543 miles.

Pearson had wanted to take his wife, Margaret, on the trip, but the “Army did not allow brides to fly in government planes.” His parents, who lived in Oregon, were disappointed that he did not bring with him their new daughter-in-law.

Returning to El Paso on July 8, 1922, Pearson flew from Portland to San Francisco. He stopped off in San Francisco to see sights and friends. He then flew to San Diego for gas, then onto El Paso. He stated “…he has just enough gasoline from San Diego to El Paso for 600 miles, the trip though is 612 miles.”

Pearson the "Barnstormer"

For pilots at this time in aviation history, crashes or crash landings were not uncommon. Many flyers encountered death defying accidents many times in their careers, and Pearson was no exception. For instance, on September 8, 1922, Pearson sent a telegram to the Commanding Officer of the12th Observation Squadron at Fort Bliss: “Carburetor trouble, Gas Line seized up. Send mechanic and tools. Land on Polo Field north of Roswell, New Mexico. Phone home. Pearson.”

In another example, Lieutenants Pearson and Paul Event crashed two miles north of Fort Bliss. Their propeller malfunctioned. They replaced the propeller, but the plane stalled, and at a 2,000 foot elevation, the plane volplaned (glided) towards the state highway, near Newman. They tried to land on the highway, but an automobile blocked the landing, so they set it down off the highway; the wheels caught, the plane’s wings crumbled, and engine motor cracked. But the straps in the cockpit held the pilots in place.

Later in 1922, Pearson was forced down near Afton, New Mexico, 38 miles west of El Paso. A windstorm caused the aviator to a forced landing. The plane suffered considerable damage, but Pearson escaped injuries. He climbed out of the plane and walked two miles to Afton.

In all of the stunt flying that Pearson and others flew at that time, crashes were common and yet, these daring young men continued to awe communities across the nation. One time, Pearson intentionally flew down a city's Main Street (location not noted) very low, over buildings.

Throughout the Midwest, west Texas and Arizona Pearson was asked to attend openings at fairs, or state holidays, to show off his plane and stunt flying abilities. In Waterville, Kansas, in the midst of a flight from Hutchinson to Fort Riley, Kansas, in honor of returning veterans from Europe, Pearson crashed again.

A brochure announced that at an air show at Scott Field, Illinois, “the latest types of planes, daring pilots, parachute jumpers, and sky writers …sky writing at 10,000 feet. Lieutenant Pearson will take the air in speed ship.” On November 10, 1921, he performed a night flight, with the plane lit by search lights from the ground, where a crowd of onlookers watched. In a display over Union Station in Kansas City, Missouri, Pearson performed loops and maneuvers like the "falling leaf." Though dangerous, these displays were a powerful, public display of Army aviation skill, and an effective recruiting method.

Soon Pearson’s fate of being an entertaining “barnstormer” of the Air Service would change. On October 23, 1922, he received orders that transferred him to McCook Field at Dayton, Ohio. From then until his death in 1924, Pearson would be stationed at McCook Airfield, where he attended the Air Service Engineering School. Upon finishing the school, he was listed on active duty and became a test pilot for the Army Air Service where he flew all types of aircrafts—standard to experimental, flying a total of 1830 hours.

NPS Photo

Air Races, McCook Field, Dayton, Ohio, 1923-24

During these years, the Army and Navy vied for the improvement of military aviation capabilities. World War I proved the value of the airplane in battle. Since that time, the military attempted to make faster and bigger planes to include in its arsenal. Pearson and other test pilots were part of this drive and at any race the military, either Army, Navy, or both, had a presence, along with their newest planes. Further, individual attempts at record speeds were common occurrences, especially in competition with France, which was one of the more competitive countries in this growing technology.

Breaking the World Speed Record

In January 1923, Lieutenant Pearson and a civilian from McCook Field, Bradley Jones, broke the world speed records. The route was from McCook Field to Mitchell Field near Mineola, New York. The previous record was four hours and thirty minutes, held by Lucian Boussotrot of France.

Pearson’s record was for 4 hours and 3 minutes. He left McCook at 11:30 am, in a DH-4 plane (12 cylinder 420 horse power, average altitude was 3,000 feet, varying from 2,500 to 4,000 feet). He flew with a very favorable tail wind, 100 miles per hour. He landed at 4:29 pm, distance of 592 miles average speed of 150 mph. A train would have taken 16 hours at that time.

Pearson’s route from Dayton was to Springfield, Columbus, Zanesville, Moundsville, OH; Pottsville, Harrisburg, Reading, and Philadelphia, PA, and Trenton, NJ, to New York.

“One of the purposes of the flight was to test instruments: lateral inclinometer, turn indicator, and a pitch indicator, designed to indicate to a pilot his position in the air, even when the pilot was not able to see the ground and make out land marks. By referring to his maps, with the aid of the instruments, he could ascertain where he was and shape his course accordingly.”

In another air show, speed air records would fall. In March 29, 1923, at an “Air Derby” at Wilbur Wright Field, in Dayton, an attempt was made to break 15 speed records in flying. It was first held in the fall of 1922.

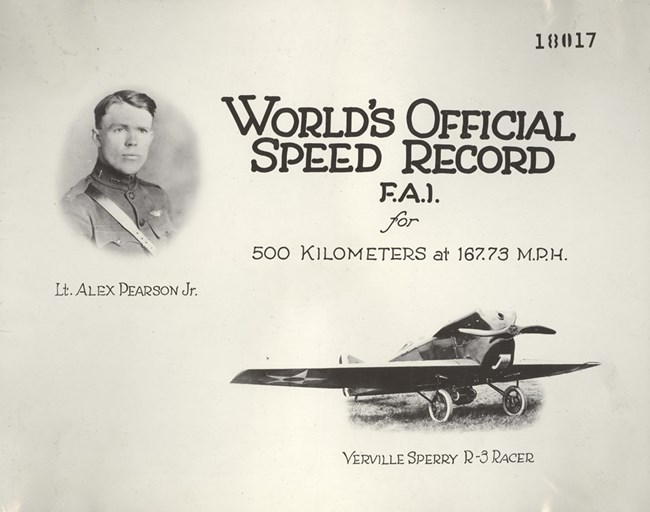

With Orville Wright officially observing from the ground, Lieutenant Pearson set a 500 km. World Speed Record of 167.74 mph (270.06 km/h) over a 10-lap course. He flew the 500 km. course in one hour, 50 minutes, and 12 seconds. This feat broke the records, again, set by Lucian Boussoutrot of France, who had averaged 86 mph, and Lieutenants Balelier and Carrier at Etampes, France, who recorded speeds at 115 mph the same year.

Pearson was flying a Verville-Sperry plane R-39 with a Wright motor. A. F. Verville was a spectator and remarked, “He was pleased in which his plane functioned and that much of the success is due to the splendid abilities of the pilot.”

All in all that day, records were set in the 500 and 1000 km. categories, beating French records for those distances. Pearson almost crashed that day, when at the beginning of the race “taking off last, after a barrel roll nearly made him crash, he steadied the plane himself and soon was going smoothly.”

Pearson the "Army ace"

In a program for September 7, 1923, at the McCook Air carnival, over Labor Day, “… in Lieutenants Wendell H. Brookley, Alexander Pearson, and “Jimmy” Doolittle, the world is promised with a modern version of the "Three Musketeers.'" The three fliers were unmatched in ability as stunt flyers (the triple stunt formation), and earned the nicknames of “The McCook Three Spot.”

At the International Air Show in St Louis, slated for October 1-3, 1923 headlines proclaimed: “With a world record for 500 km. to his credit, Lieutenant A. Pearson looms as the army ace in the speed event. He will oppose the Navy’s new racers with a Verville-Sperry, the only mono-plane entered.”

At the Lambert-St Louis Field, on September 28, 1923, Pearson broke a record of the Pulitzer Racer, which had been made a year earlier by Lieutenant Russell O. Maughan, flying at 205 mph. Pearson flew 230 mph in a trial run. He made his run during a storm, when no other flier dared to go up. Pearson’s Verville-Sperry monoplane with a Curtiss CD 12 motor was numbered 48. His plane’s wheel, after takeoff, folded under the plane to provide less air resistance.

For the Pulitzer Air Race in St Louis, October 1923, the course covered 489 acres, and featured a grandstand for 45,000 attendees, a bleacher for an additional 10,000 spectators, and a concourse holding 30,000. The parking a lot could hold 15,000 cars.

Pearson flew a Verville-Sperry, but he developed engine problem with his propeller and it forced him down. Normally, a pilot was not able to race in the Pulitzer Races every year. But because of his problem of not being able to race, he was notified after the race that “he would be able to compete in 1924, because of the issues with his plane….” in a letter from Chief of Air Service, Mason M. Patrick

Between 1922 through 1923, October to April, American flyers broke 12 world-wide air records. The records which were broken, showed that “every flight made and every record attempted is done to test or prove some scientific fact …they have a predetermined military and commercial value.”

In June 1924, Pearson flew over the tornado damaged towns of Lorain and Sandusky, Ohio. His co-pilot was “Doc” Burka. He flew at an altitude of 200 feet so pictures could be taken in order to assist in the rebuilding of the town. Hundreds of homes and businesses were destroyed; eight deaths were reported in Sandusky.

Continuing his attempts at world speed records, on June 24, 1924, Pearson piloted a Douglas Cruiser. A 50 kilometer course with three turning points was created at Wilbur Wright Field, New Carlisle Field, and McCook Field. These races will deal with “specific loads,” and “loads at certain altitudes.” Attempts were made for altitude, distance, and endurance. Speed for ships carrying the same weight over measured 100 and 200 km. courses.

NPS Photo

Pearson's Death: September 2, 1924

On September 2, 1924, while preparing for his second Pulitzer Race at Wilbur Wright Field, Lt. Alexander Pearson's died in an aircraft crash at 7:15 pm. At the time of his death, Pearson was making test flights over the race course. He had been in the air for 15 minutes when the crash occurred.

He was flying the Curtiss R-8, a Navy racing plane. He was reportedly flying at over 200 mph. While practicing a diving start, the plane’s wings collapsed (the strut failed as he attempted to recover from a dive) and his plane crashed into the ground from an altitude of 30 feet, at 260 mph.

It was reported that Pearson "came down out of a dive to get added momentum of a fast start and flattened out for a horizontal flight. Just as he started upward again, the ship enveloped into a cloud of black smoke…then took the appearance of a bundle of rags. The crash was heard for about a mile around.” Pearson died instantly.

The cause of the crash was due to the hollow laminated interplane strut, which placed tremendous pressure on the wings. The strut was subject to high-speed flutter. Later, the Army and Navy replaced the planes with solid struts and demanded pilots wear parachutes.

The engine of Pearson’s plane was found embedded three feet into the ground, 10 feet from the plane. The engine struck the concrete abutment of an old war hanger. Pearson was found crushed and bruised, 20 yards away. He either leaped from the plane at the last minute before the crash or the plane threw him. He was not wearing a seat harness.

Pilots Brookley and Skeel, flying with Pearson that day, were in the air when the crash occurred. Brookley saw the accident and landed immediately; Skeel did not hear of the crash until he landed.

Pearson’s wife, Margaret, who witnessed the crash, rushed to the site of the wreckage. Overcome with grief, she had to be put under a physician’s care and was taken to their home in Dayton.

An eyewitness, John Marius, who was playing tennis nearby, saw the crash. The crash was close enough that wood splinters and metal debris stuck the tennis court and Marius.

The night before, Pearson had been practicing flying his plane over Dayton, flying and diving over McCook Field. The powerful motor could be heard for miles around.

His control of the Curtiss R-8 was superior, according to friends, who claimed that “his control of a ship is such that he can make it lie down and say uncle.”

NPS Photo

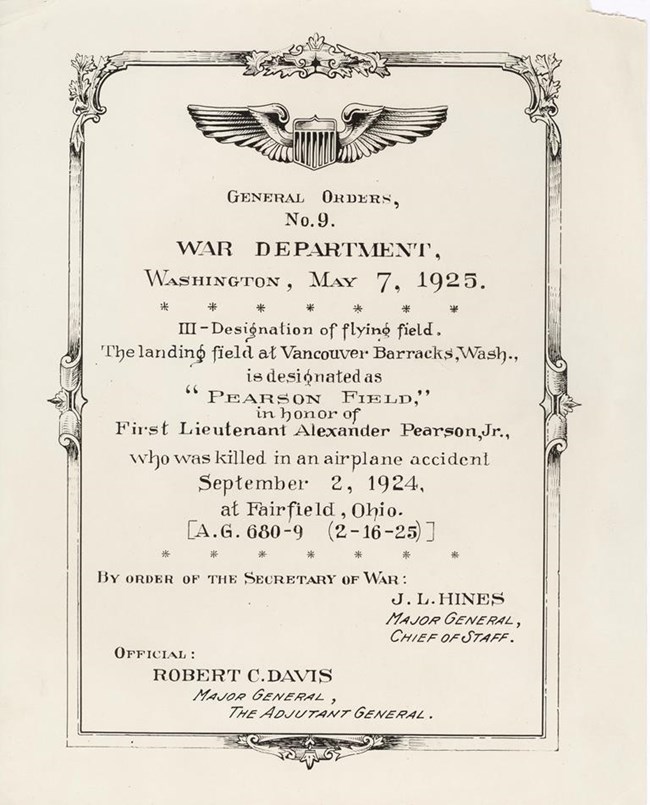

The Dedication of Pearson Field, September 16, 1925

On May 7, 1925, the airfield in Vancouver Washington, formerly known as the Vancouver Barracks Aerodrome, was designated Pearson Field, in honor of Alexander Pearson. That year, on September 16, the field was formally dedicated with a large public event, overseen by Lt. Oakley Kelly, the new commander of the airfield. Margaret Pearson was also in attendance.

The dedication featured an impressive aerial show, with over 52 planes, including DeHaviland and Curtiss airplanes, and commercial airplanes. 20,000 people were in attendance. Despite an array of death-defying performances that included stunt flying, wing walking, and parachute drops, no crashes occurred.

Today, Pearson Field is a municipal airport for the City of Vancouver, and is one of the oldest continuously operating airfields in the United States. Adjacent to the airfield is Pearson Air Museum, also named after Alexander Pearson, a part of Fort Vancouver National Historic Site. This National Park Service museum tells the story of early aviation at Vancouver Barracks and Pearson Field. There, the legacy of Alexander Pearson and the aviation pioneers that flew at the field that bears his name are honored through exhibits, programs, and events.