Article

World War II Aleut Relocation Camps in Southeast Alaska - Chapter 3: Funter Bay Mine, pt. 1

Villagers from St. George were housed at the shoreside camp of an old gold mine on Funter Bay (Figure 57). The Admiralty Alaska Gold Mine is a collection of old buildings including a mill, a road and tramway inland, two adits and other workings, and the seasonal homes of Sam Pekovich and Andrew Pekovich. The mill and mining camp are located about one mile from the cannery, on the southeast shore of Funter Bay (Figure 9). The mine is patented land owned by Sam and Andrew Pekovich and the Admiralty Alaska Gold Mining Company, and includes old mineral claims going back to the late 1890s. The land near the coast is gently rolling and steepens inland to become Robert Barron Peak. A thick forest of hemlock and spruce, with some cedar and fir, blankets the landscape (Guard 1958:6).

Early Years

The claims were originally staked by Richard G. Willoughby, a prospector and opportunist who worked his way north along the Pacific Coast in the mid-19th century, arriving in Wrangell by 1875 (DeArmond 1957). Willoughby was a contemporary of Joe Juneau and Richard Harris – the historical discoverers of gold at Juneau in 1880. He subsequently kept a cabin in Juneau on the street eventually named for him, becoming “one of the best known pioneer miners in Alaska”(New York Times 1902). Between July of 1888 and January of 1889 Willoughby and his partner A. Ware staked ten mineral claims on the southeast shore of Funter Bay (Chipperfield 1935). The territorial governor reported in 1891 that the Funter Bay mine “has continued its usual activity” (Knapp1891:30), but the details are unknown. Six years later Willoughby (without his partner) amended the claims, according to Chipperfield (1935), and in 1902 he died while in Seattle (New York Times 1902).

Alaska State Library Winter and Pond collection PCA 87-0394

The Territorial Commissioner of Mines (Maloney 1915:12) reported in 1915 that “the old Funter Bay mine on Admiralty Island has been reopened and “was operated on a profitable basis during the year.” On December 20th or 29th, 1919, Henry Roden, W.S. Pekovich,and other citizens of the Territory of Alaska incorporated the Admiralty Alaska Gold Mining Company with control over Willoughby’s claims, according to documents in the possession of mine investor, officer, and caretaker Andrew Pekovich. By then several owners had come and gone, according to Pekovich – a son of Serbian immigrant W.S. Pekovich. The Admiralty Alaska Gold Mining Company was formed to develop the Funter Bay claims, and the sale of shares funded construction of a waterfront mill and support buildings (Figure 58), plus a rail line to workings including two adits inland at the base of Robert Barron Peak. In July of 1923 the Admiralty Alaska Gold Mining Company amended and recorded Willoughby’s ten claims (Chipperfield 1935).

U.S. Geological Survey geologist A.F. Buddington (1926:46) described the Funter Bay deposits as mostly gold-quartz veins accompanying the Mertie Lode – a mineralized sulphide at about the 2000’ elevation and 6000’ from the mill. By 1929 gold-quartz veins had been mined from four claims: the Tellurium, Uncle Sam, King Bee, and the Heckler Blanket, and three concentrate shipments were sent to the smelter at Tacoma in 1926 and 1927 (Eakin 1929:6-7). W.S. Pekovich left the Board of Officers to serve as General Manager during those years, according to Andrew Pekovich.

The 1930s were generally good years for mine operators, at first because of the Depression’s cheap labor, then inadvertently in 1934 because President Franklin D. Roosevelt made private ownership of gold illegal, forced citizens to sell to the government at $20.67 per ounce, and subsequently revalued it at $35 per ounce (Saleeby 2000:33-34). But the Admiralty Alaska Gold Mine had little if any production during those years. In 1935 the company applied for a patent to the ten Funter Bay claims, prompting the USFS District Ranger’s report (Chipperfield 1935) and leading to legal ownership of the land. Chipperfield described the buildings and workings, and their condition, and opined that the claims had been idle for the three prior years.

The lack of activity noted by the USFS District Ranger in 1935 reflected the Funter Bay mine’s corporate officers’ attention being focused instead on mining to the south at Hawk Inlet. In addition to being an officer for the Funter Bay mine, Henry Roden was also President of the Alaska Empire Gold Mining Company according to a December 12, 1932, letter submitted with a Hawk Inlet mine report by Juneau surveyor Frank A. Metcalf. That company was associated with the Hawk Inlet Gold Mining Company (Alaska State Library 2002). W.S. Pekovich was also General Manager for the Alaska Empire operation and lived at Hawk Inlet with his family for much of the time between about 1932 to 1950, reports Andrew Pekovich, leaving his father’s cousin Rado Pekovich as caretaker at the Funter Bay mine. Connections between the mining companies were strong, with suggestions in the archival record that claims and equipment were shared or exchanged (Stewart 1933:13; Townsend 1941). Together they controlled 200 claims stretching from Funter Bay to Hawk Inlet (Stewart 1933:13).

Strategic material surveys conducted in support of World War II prompted the U.S. Geological Survey to assemble existing mining reports for government review. Geologists A.F. Buddington’s notes and reports of visits to Funter Bay in 1936, 1937, and 1938 were used by geologist John Reed (along with his own visit) to evaluate Funter Bay’s potential wartime mineral contribution in 1942. Of interest was the nickel-copper component of the Mertie Lode higher up the slope of Robert Barron Peak, but Reed’s (1942) report judged the ore grades insufficient to warrant mining.

Alaska State Library Butler/Dale collection PCA306-neg898.187 (Aleuts)

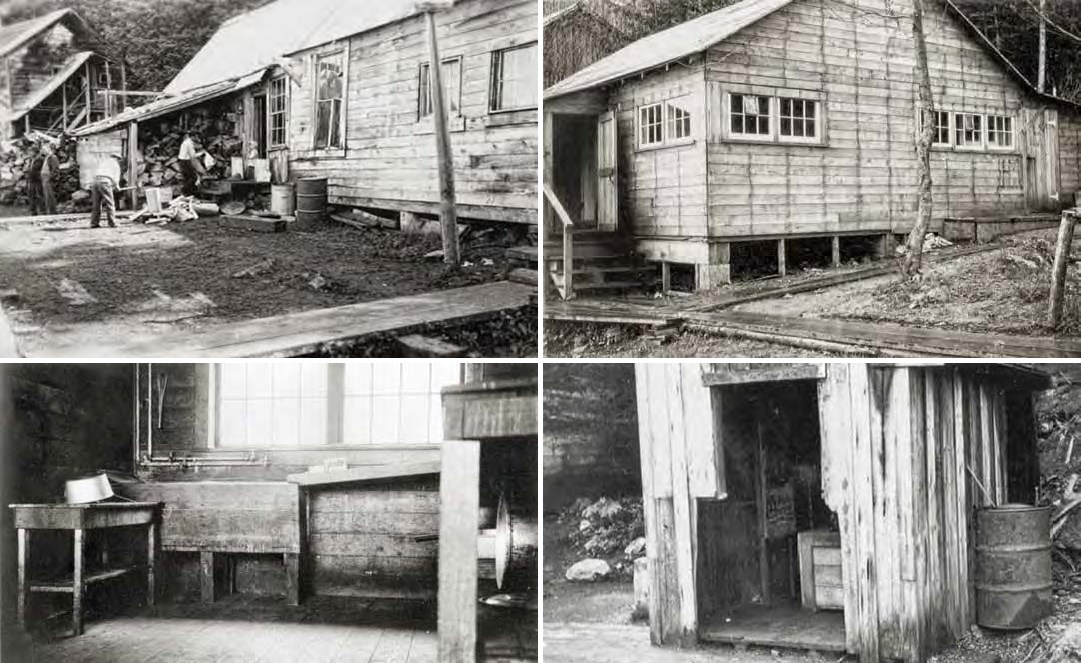

A map made in August of 1942 shows most of the original shoreline buildings described by Chipperfield seven years earlier (Figure 59). All the buildings were of frame construction. Dominating the shoreline was the tall mill building, measuring 40’ x 60’, with its steep, conspicuous roof. A tram track from the upland workings dumped ore from a cart into the top of the mill to begin the processing system. In a typical mill of the period, the ore would fall onto a “grizzly” or grate and be sorted for feeding either directly into a battery of stamps or through a crusher first and then the stamps; from there the finely crushed ore would progress down through the mill across amalgamating plates and on to concentration tables (Sagstetter 1998:56). In 1935 Chipperfield noted that the ten stamps once operating at the mill had been removed. A photograph of a building said to be the assay office incidentally shows a pile of vanner rollers (Figure 60), providing more detail about the ore concentrations and sorting systems. Other major industrial features on the shoreline were a shop and an assay office, plus one and then later two wharfs (Figures 58-59).

Many of the shore buildings mapped in 1942 were for housing. Two buildings on the north end of the alignment were “permanently occupied” – one by Rado L. Pekovich, who was identified as the watchman, and the other by Mrs. S. Pekovich – the first wife of W.S. Pekovich. A two-story 24’ x 50’ bunkhouse on pilings over the intertidal zone, with space for 20 people, was described as unfinished in 1935 by Chipperfield. An older bunkhouse (Building E), identified as 2-story from photographs (Figures 58, 61), measured 20’ x 40’. Three buildings are identified as “living quarters,” with three or four rooms each (Figure 59). Other dwellings consist of one “bungalow” and a couple “shacks.” Two buildings (one 20’ x 40’, the other 24’ x 40’) are listed as “mess house,”each with a secondary function – one had storage rooms, the other was used as a warehouse and office with a dormitory in the loft. The 1942 map doesn’t plot the mess house with storage (Figure 61) because it burned down within a couple months of the Aleut arrival.

Fig. 61: University of Alaska Fairbanks Fredericka Martin collection 91.223.3417

Fig. 62-64: Aleutian Pribilof Islands Association (copy print, source unknown)

Utilities for the mine were simple. Water was piped to a large laundry/toilet/shower building south of the mill –Building T (Figure 62). The source was either a small impoundment box on a creek to the southeast or via the existing large 3’-diameter penstock laid in a ¾ mile-long ditch to serve the milling process. A WW II period photograph of a kitchen interior shows a wood washing basin served by two independent sets of 1” pipe, indicating a hot-water heater (Figure 63). An outhouse serving the southernmost dwelling (Building R – the home of “Smiley” Jukich, the maternal grandmother of Sam and Andrew Pekovich) was perched over a small creek about 30’ from the high tide line. Outhouses serving the remainder of the pre-war mining camp are not identified on the map and may have been attached to one or both wharfs extending into the bay. Two small buildings near the tide line identified as women’s toilet and men’s toilet (Figure 59) were almost certainly constructed for the mine’s new wartime occupants. A wartime photograph shows a third outhouse on land upslope (east) of a shoreline boardwalk (Figure 64).

The Admiralty Alaska Gold Mine had more than one power source, though likely not all were in operation at once. Installed in the mill were two large 100 horsepower Seymour-MacIntosh diesels, accounting for one system. According to Sam Pekovich, another generator was housed in a shed just east across the boardwalk from the bunkhouse (Building L; though the small building isn’t plotted, it shows on WW II photographs). Serving the mine adits and aerial tram was a large onsite Pelton wheel. Archival photographs show poles and overhead electrical lines extending north at least to Building B, and – since the northernmost cabin A was identified as “permanently occupied by Mrs. S. Pekovich” – the line probably extended to her home also.

World War II and the Camp Experience

By June of 1942 the Admiralty Alaska Gold Mine had been out of production for at least 15 years, and no longer was there the need for a large crew of workers or the shoreside facilities to serve them. Rado Pekovich was the mine's onsite caretaker and at least one other related individual lived there, while the W.S. Pekovich family lived (until about 1950) at nearby Hawk Inlet. Negotiations between the federal government and representatives of the mine are evidenced in the archives only by a July 15, 1942, letter sent from USFWS General Superintendent Edward C. Johnston in Seattle to Alaska Indian Service agent Claude M. Hirst in Juneau, implying that initially the President of the mining company (probably still at that time Henry Roden, a well-connected territorial politician) wanted $250 per month to house Aleut evacuees. Ultimately the mine was leased for one dollar per year, according to Pekovich family members.