In October 1943 our fifteen planes and crews took off from Whidbey Island, Washington, headed for the Aleutians. A nine month experience of fighting a war against weather and the Japanese lay ahead. We made stops, usually overnight, at Ketchikan, Kodiak, Cold Bay and Adak before arriving at our first Aleutian “home” – Amchitka. Each island seemed to be more desolate.

We carried three 500 pound bombs, putting our total weight, wing tanks and all, at well over the supposed “maximum overload.” Thomas Erickson

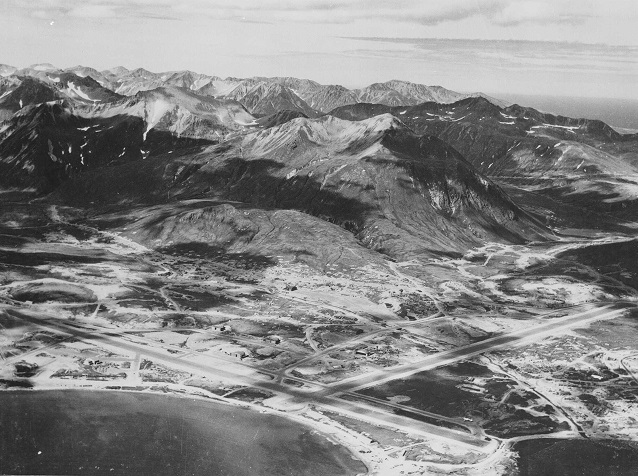

Photo courtesy of Robert H. McGinnis, from the collection of Clifford F. McGinnis, Post Engineer, Amchitka. Dec 1944-Jan 1946.

Life in the Aleutians

Amchitka, like most other Aleutian islands, is not very big, perhaps 20 miles long by a few miles wide, with jagged mountains over most of it and some areas where runways (steel mats) and Quonset huts could be placed. Heating was primitive. We slept on cots – in sleeping bags. Out houses were, well, outhouses. More than once I would trudge through a foot or two of snow on a wild winter’s night to get to one, then have the discomfort of icy blasts of sub-zero Arctic air attack a part of my body that was unaccustomed to such treatment.

There were pluses. The food was passable, though I never could get used to powdered milk. I tried coffee but didn’t like it (and never have). The free time was plentiful – for bridge, poker, reading, writing letters. Some liquor was available. I think a bottle of Three Feathers (indelicately referred to as Old Panther Piss) cost about $2.00. We were grateful we weren’t Army foot-soldiers in Europe or Marine/Army island assault troops in the pacific.

On Amchitka our mission was to fly constant reconnaissance runs in pie-shaped sectors of the Pacific Ocean. We were on the lookout for enemy ships, surfaced submarines or aircraft. We had radar capability. On an average mission – and there weren’t very many of those – we were aloft 4 ½ to 5 hours. Each crew flew about every other day.

Willywaws, snow, and the Aleutian weather

It didn’t take many flights before we realized that our main enemy was the weather. As winter approached we soon moved our base on out the chain to Adak. The norm of rain and high winds turned into sleet, ice and higher winds. Muddy walking areas became snow trails. One wild night, I believe it was on Adak, the wind got so fierce that the six of us in our Quonset house thought that we – and the hut- were going to be blown away. When the hut started rocking a little we all pushed against the windward interior wall. What probably saved us was the snow that built up on the outside of the semi-circular shaped roof-siding. The next morning we had to dig our way out of the hut. The huge snow drift was within a foot or so of covering the flue atop our hut.

Photo courtesy of Don Brydon

Most of our nine month stay in the Aleutians was spent on and about the farthest-out island – Attu – a small level area on one corner, surrounded by precipitous mountains covered by ice and snow. When the wind direction required us to take off from the only runway (steel mat, of course) in one direction we were headed at the nearby mountains, making necessary a rather quit right turn after leaving the ground. Getting too close to the mountains was dangerous because of some wild and unpredictable wind currents called willywaws [sic].

Bad winter weather at Attu could mean anything from huge snow storms with winds that reached over 100 mph to thick cloud cover that could reach down to water level. No, we did not take off during major storms, but if there was almost any visibility and winds less than 50 mph or so we’d go. The reason was quite simple – the worse the weather the more likely Japanese sneak attacks (the invasions?) would be. One nasty day on a patrol plane – not one of our squadron – sent a radio message back that, when decoded, said that a major enemy fleet was headed toward Attu. We were alerted for action. Shortly we were told the report was false – the reporting plane had used the wrong day’s radio code!

Our Quonsets were near Murder Point, the next to Massacre Bay, names that remained from the days decades before when the Russians slaughtered the native Aleuts on Attu – for unhindered fishing “rights,” I was told. We saw some of the simple graves of those Americans who, just a few months before we got there, took Attu from the Japs in one bloody battle after another. One Japanese soldier had somehow survived in the mountain wilds, but he apparently could not resist trying to get some food from us. He was caught standing in our chow line. I don’t know what happened to him, but it was probably much better than what happened to many American prisoners of the Japanese.

A few times we could not land on Attu after a recon flight because of zero visibility. I remember one time when we luckily found a hole in the overcast and made it into Shemya, a tiny, flat island not too far from Attu. There was a landing strip plus a few Quonset houses and almost no personnel. Its only purpose was as an emergency landing field – for planes such as ours. We slept on the floor in a circle around an oil heater, grateful that we always took along our sleeping bags for just such needs.

A brush with celebrity leads to a broken promise

One of the huts was nothing but the shell aground a long string of toilets – wooden seats on holes in the ground. Of the fifteen or so such “thrones” I was the only occupant when a tall balding man in civilian clothes came in, nodded a greeting to me, sat down on a seat next to me, performed noisily a necessary bodily function, then smiled, turned to me and uttered his first words – “That’s the first good s--- I’ve had in three days.” (Sorry, old ladies!) It was my introduction to Errol Flynn.

We talked for quite a while. He told me he was on a USO tour with a young starlet named Martha O’Driscoll and would be giving a show or two on Attu “if we ever get to that g.d. island.” Mainly he was complaining – about everything – but he did ask if he could do anything for me (contact my wife, parents or whoever). I said that, as a matter of fact there was something – take a live blue fox back with him and deliver it to Mario at the Blue Fox café in San Francisco with the compliments of Navy squadron VB-139. I told him the background and that just a few days earlier my squadron mates Al Daniel and Brad Bradbury had led a small hunting group on Attu in search of a blue fox – and were successful. The CB’s built a cage for it, and our only problem was that we were told we could not take it with us when we returned later.

Flynn said yes, enthusiastically, then gave me a long profane commentary on his need for some good publicity.

His plane and ours got back to Attu the next day. His show, for the Army, Navy and Marine personnel on the island, was informal, funny, a great diversion from our truly barren lives up there, BUT, believe it or not, it was too off-color. And be assured they were not performing for a bunch of prudes!

We turned the blue fox over to him at departure time and asked him to give Mario our best. Al Daniel gave him a large box of “fox food.” I have no idea what was in that box.

The Spokesman-Review, Friday, December 31, 1943

About three weeks later a Northwest Airline plane came into Attu with mail, newspapers and supplies. One week-old Los Angeles Times paper had a Hollywood gossip column in it by Hedda Hopper with a paragraph that went something like this…”Errol Flynn is back in town after a triumphant USO tour of the Aleutian Islands, and guess what he’s inviting the girls up to see – a live blue fox!”

Many months later when we returned to the States we called Mario and were told that he never heard from Flynn. Nor had any of us. I now have an ugly habit of muttering profanities when I look at Errol Flynn reruns.

Aerial Bombing

Back to Attu…Some higher-ups decided that any kind of aerial bombing of north Japan might induce the enemy to bring additional defenses up there to thwart any invasion efforts by the U.S. More northern defense would mean less defense in the south. Since the 1500+ mile round trip between Attu and Paramushiru was beyond the PV’s limits some geniuses found a way to install a gas drop tank under each wing, giving us the additional fuel we needed for the long trip. One minor irritant was that there were no gauges for these tanks. Since we wanted, of course, to use every drop of gas we could from these tanks before switching over to our main supply, the only way we had of knowing when a tank was empty was when an engine started sputtering. The co-pilot’s job (mine) was to switch at the first sputter. Just another hazard at 10,000 feet over the middle of the North pacific Ocean in a pitch-black winter’s night with icy precipitation and no visibility sometimes.

Formation flying was impossible in that weather, so we went one at a time, three or four per night when take-off weather permitted. Usually we took off around midnight to put us on target by dawn. We carried three 500 pound bombs, putting our total weight, wing tanks and all, at well over the supposed “maximum overload.” Our bombing technique was as primitive as you can get – fly over at around 10,000 feet, try to arrive at dawn, watch out for “Charlie” (an old Japanese trainer plane that would fly around and radio back our altitude to anti-aircraft gunnery positions), swing lower to 1000 or so, then by visual or any other means drop the bombs on or near any area with buildings, lights, gunfire or whatever – then get the hell out of there. Anything down there was military, we presumed. The main point was to let the Japanese know that we could and would get bombers to them up north.

McKinney and I made five of these trips, the last one of which was, without any exception, the most harrowing experience of my life.

First, some background.

A special date and a close call

The only females on the island were eleven nurses, who were quartered in a large Quonset hut that was completely enclosed by two concentric circles of barbed wire fencing about ten feet high. (One lieutenant-commander, not in our squadron, had returned from a tough flight, got thoroughly soused and was caught trying to claw his way through or over the inner fence. Getting over the outer fence had made a bloody mess of him.)

One of our pilots, Phil Brady, was badly hurt in a takeoff crash. Fortunately he recovered, thanks in great part to the nurses. When he was well enough to be released the nurses got permission to have a special party for him at the large common room in their quarters. It was a juke-box, dancing, cake and cookies kind of thing (there may have been beer, but I can’t recall). Phil invited ten of us to attend. Eleven guys, eleven nurses. Shortly after this evening party started the nurse with whom I was paired off said she wasn’t feeling well and disappeared. My buddies seemed to be having a good time, and I did too, cutting in on dances and conversations.

Photo courtesy of Clint Goodwin

At one point the door opened and in walked Olivia DeHavilland, having just finished a USO visit to those in the island hospital. Everyone clapped. She of course was spending the night with the nurses, and she accepted the head nurse’s invitation to join the party. I was the only “unattached male,” making me the lucky one to have a date after all – and what a date!

We talked, we danced, we ate cookies and drank lemonade and we smoked! She asked about what our squadron was doing, and when I told her we were scheduled for a flight the next night she stated flatly that she was going along with us. She said “If Joe E. Brown can go on an over-the-hump flight in India I can go on a Navy flight in the Aleutians.” I promised to call her the next morning after I talked with my superiors.

I talked with Grange McKinney, my pilot, about it, and we ended up agreeing that, exciting as it sounded, it was a bad idea for many obvious reasons. I called her the next morning and was immediately greeted with the news that the Army major supervising her trip gave her an emphatic “NO.” It turned out that the last thing we needed on the trip we were about to make was more weight, let alone a female.

We made our bombing pass right after dawn, with a few breaks in the cloud cover giving us some help. When we dropped the bottles and as I watched, a ground search light suddenly went out. I told Grange I felt sure some bottles knocked it out. If so, sheer luck.

We left, climbed to 10,000 feet, saw a Japanese “Betty” bomber not far away, then entered a misty ice-fog. Changing altitudes did not help, but we were glad to have our wing-deicing equipment – rubber leading edges on our wings that, when activated, would pulsate and knock off any ice accumulation. It was smooth flying – an eerie calm with no visibility. Our navigator could only go by earlier estimates of wind direction.

Quite abruptly our air speed indicator went back to zero, the only explanation we could think of being an icing over. Flying any airplane without knowing your airspeed is difficult in good weather, much more so in what we were going through. Knowing our altitude was the key. Fortunately the altimeter worked.

Before long we could see ice slowly building up on the leading edges of the wings. At the same time Grange found he had to apply more power, little by little, to maintain altitude. The rubber wing “boots” could not shake off the ice. To preserve precious gas and in the hopes that lower altitudes would help we slowly descended. For the next 20 to 30 minutes we were both descending and increasing power, going from around 8000 feet altitude to 2000 or so, with no changes.

Then with almost full power on, we suddenly broke free from the ice-mist at less than 1000 foot altitude and just ahead on our left was a huge rocky formation with waves breaking on it. We were supposed to be about half way home with nothing but ocean for 350 or so miles of water ahead and behind us and 150 miles south of the nearest land – the southernmost tip of the Russian Komandorskie Peninsula/Islands.

After a quick huddle with our navigator, Grange and I agreed with him that the only explanation was that we were 150 miles off course, driven by south-to-north winds instead of the reverse. That big rock had to be believed. Quite literally our lives depended on it. We were way north.

As we changed course and as the ice disappeared from our wings we had major decisions still to be made, mainly at what altitude and air speed could we best have enough gas to get us back “home.” We knew it was going to be close.

High on my list of “the most beautiful sights I’ve ever seen” is that first little black spot on the horizon…then the close-up view of that jagged, mountainous rock and ice called Attu.

After 9 ½ hours in the air we landed with enough gas for, we were told, about five more minutes of flying.

Courtesy of USAF, Elmendorf Office of History

Last updated: January 19, 2018