This bit of recollection and memories, accounts the good, bad, humorous and not so humorous events that transpired aboard the vessel officially named Barge Self Propelled 1923.

As all this unfolded before the eyes, one had to have a feeling of pride to be part of such a mighty effort of men who were to overcome the many pitfalls of this storm and foggy chain of islands.

It has been said at various times, that the U.S. Army had more ships than the U.S. Navy. It may well have been factual. The Army Transport Service (ATS), mainly a civilian operation, did indeed operate large troop transports and supply ships. This story deals with the small coastal and interisland vessels, the Power Barges – Tugs – Freight Passenger ships that were of a support nature, working the waters of Alaska and the Aleutians, supplying equipment and food, and on occasion transporting troops and civilian hires to various work sites.

This bit of recollection and memories, accounts the good, bad, humorous and not so humorous events that transpired aboard the vessel officially named Barge Self Propelled 1923. The crew assembled for the voyage, consisted of seven Army personnel, one of which was the ships mate, another an assistant engineer, a cook, and four deck hands. To offer experience there were two civilians in the employ of ATS. One was denoted skipper (Captain), the other chief (Engineer). The military members had for the most part arrived in Seattle as infantry troops, fresh from basic training in the southeast United States. Due to the retaking of Attu and Kiska and the occupation of other islands we were evidently surplus infantry and shortly after arriving at Fort Lawton near Seattle we became detached to the Harbor Craft Detachment. To this day most members do not truly know whether we were part of the Alaska Defense Command or the Transportation Corp. Later came another area title: The Alaska Department.

Recalling the various shoulder patches worn by the Harbor Craft Members; the Transport Corp wore what would be a motor vehicle wheel with spokes extending beyond the outer edges, evidently to appear as a ship control wheel. The ADC patch pictured a seal with its nose balancing the letter “D” with the letters “A” and “C” appropriately on each side. Though not remembering the colors, it was a most attractive patch. The Transport patch did not find many places on shirts, field jackets, and other apparel. The seal was the thing but it was not officially allowed at that time. Most wore the white polar bear on a blue field with the golden North Star centered above the bear’s head. It was said General Simon Buckner thought the seal should show an animal, and so adopted the Polar Bear patch showing the ferocity and strength of his command, the Alaska Dept.

Courtesy of Betsy Ugalde (daughter) from the collection of Samuel M. McKay

Setting Sail for Alaska

The BSP 1923 was manned in early December 1943, made a trial run from Seattle, through the Puget Sound to Everett and returned. On or about December 21, 1943, we departed Seattle, with a cargo of railroad ties. It appeared our destination was Seward, the ocean port for the Alaska Railroad or perhaps Whittier in Prince William Sound. Either as home port was of satisfaction. The mainland offered bars, restaurants and girls. It would be just like the lower 48. Young men are always optimistic. In two and a half months we would be far from the bright lights of everyday life. The Cruise of BSP 1923 had begun.

Our power barge, though not a ship of beauty, was a very practical work boat, and quite seaworthy in spite of its nearly flat bottom. (A friend, the first mate recently remarked, that to his knowledge not one ever capsized or broke up in open water.) There were various series of power barges with slight differences in length, type of engines and other smaller modifications. Ours, the 1900 series was 85 feet long and powered by two caterpillar engines each developing [blank space] horsepower, with a cruising speed of eight knots per hour. Two rooms approximately eight foot square, housed the crew members, with four men in each, two lower, two upper bunks. The captain had private quarters, but only of modest size. The dining space and galley were one, perhaps 10’ X 12’ in area. Below, on the main cargo deck, and at the stern was the head and a food locker. It was compact, but adequate for our needs.

Leaving Puget Sound in our wake, we entered the Strait of Georgia with the British Columbia mainland to our starboard. Continuing on through Johnstone Strait, we moved out onto the open water of Queen Charlotte Sound in the early evening of December 23. A westerly gale was in full force, piling up heavy swells. This was our first experience in strong seas. We bounced, shook, and rolled to the extent that the skipper turned about and entered the calm waters of the little village of Alert Bay. We remained at the dockside that night and throughout the next day before Christmas.

Photo courtesy of Betsy Ugalde (daughter) from the collection of Samuel M. McKay

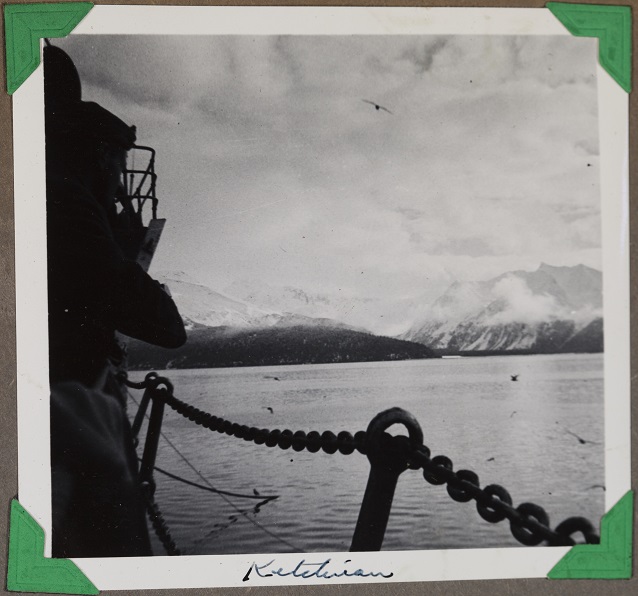

On Christmas Day, with moderating seas, we again moved northward through the sound, and Hecate Strait, and tied up at Ketchikan (all dates beyond December 25 remain vague) some days later. After an overnight stay we continued on, stopping one day at Wrangell and another at Juneau. We had yet to experience sailing in a winter storm in the North Pacific.

A few days following New Year’s 1944 we exited Cross Sound and in a few hours were in the grip of a heavy snow storm with winds in the vicinity of 50 to 60 knots. The seas were running with swells of 50 feet. The Skipper remarked that we were taking green water over the pilot house. We were hearing that term for the first time and though not knowing its meaning, I knew it was not good for comfort. We would be at the bottom of a wave looking upward at the spray blowing off the top of the next swell, and as we climbed it, or it passed under us, the ship would vibrate and shudder with both propellers out of water momentarily, as we prepared to slide downwards once again. We did manage the crossing and entered Prince William Sound making another stop at Whittier, then proceeding to Seward. I cannot recall if we unloaded our cargo of rail ties. I cannot recall what other cargo we might have carried westward.

It must be said we were being indoctrinated in the art of sailing and seamanship in a speedy manner. The only problem we truly suffered from was that our cook and the one who was to replace him were both plagued by seasickness quite easy and often. They would take to their bunks at the first sign of choppy water.

Though starvation was never to occur, the crew members had to shift for themselves. One cook named Leo, claimed he was formerly employed at the Palmer House in Chicago. No offense to Leo, but after many of his meals, we quietly questioned to ourselves what his duties were there. Our second cook, a Louisianan called Rabbit, came to us after being transferred from a river boat, assigned to the Kuskokwim River to supply Army posts between Bethel and McGrath. He would often tell of his hellish journey from Wrangell; of being towed across open water in a perfectly flat bottomed boat. Besides being a decent cook, he was also a compulsive gambler, preferring dice to cards. He consistently lost most of his monthly pay, (at that time about $75.00), but always told us that his fortune would change, and reminded us of his big hit (winning) one night at Bethel.

Photo courtesy of Robert and Shirley Johnson

On to the End of the Line

After leaving Seward we sailed nonstop to Dutch Harbor. About this time, we were told our goal would be Attu. I do not recall much conversation about that being our home port but certainly no one looked with good feeling at being at the end of the chain of islands.

Our next port of call was to be Adak. I would estimate that in most instances we never ran much more than five to ten miles off the coastline, and on this occasion we did not do differently. Somewhere north and east of Adak we ran into a severe storm. The seas were not extremely high though and the winds were blowing at a great velocity. They were from a west to south, southwest direction and the islands to portside allowed us to be somewhat in their lee. Our problems were visibility and location. At that time there were no navigational aids beyond Dutch Harbor. Our vessel had no equipment except for a compass and a two-way radio. The Army had given little instruction on whom to call if assistance was needed. For over a day we had moved cautiously south to make visual contact with the shore. (This is hearsay on the civilian skipper’s part but he said during the past night, a Liberty Ship came upon us and asked by light signal if we cared to abandon ship. His reply was negative, but, if the Liberty cared to abandon their vessel he had doubts that we had space for her crew. True or not I cannot say.)

I came into the pilot house in the evening to take my turn at the wheel and prior to my arrival the skipper and others had observed lights from ashore. Quite likely this was Adak, due to the number of lights and it being the largest U.S. Base in the Aleutians. But the question remained – what part of the island were we viewing through the wind swept snow? Through the night we would move inward to where we could see the lights and let the wind carry us back out. We would continue doing this while waiting for the storm to subside and with improving visibility we would find our way into Kuluk Bay. Suddenly, off our port bow two floodlights illuminated us. It was somewhat of a scare until we were to make out that it was a naval minesweeper. Evidently shore radar had picked us up on their screen. By light signal they informed us they would hang a lantern on their stern and we were to follow. I do not know their speed but within 30 minutes we had lost sight of them, but by now we had some knowledge of our position and continued toward Kuluk Bay. At the entrance we again came upon the minesweeper standing by to guide us in. Unknowingly in attempting to pass her on our port side we now found we were hung up on the submarine net protecting the harbor. After some labor and cursing we freed ourselves and found our way to the Army dock and tied up alongside another vessel. Another undesired experience completed.

Adak at this time (January February 1944) was the hub of all activities in the Aleutians. I do not recall air traffic but ashore streets had been laid out, warehouses and Quonset houses had been erected, bulldozers, heavy trucks, and earthmovers were chewing at the soil for installations to house troops and supplies. The harbor was full of naval vessels, freighters, and tugs and power barges like the 1923. We were to remain here for only two days and again sail westward.

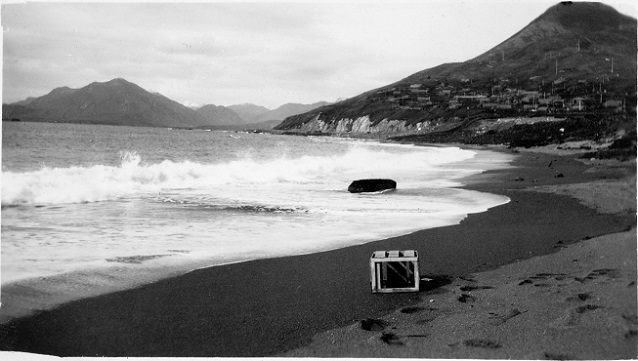

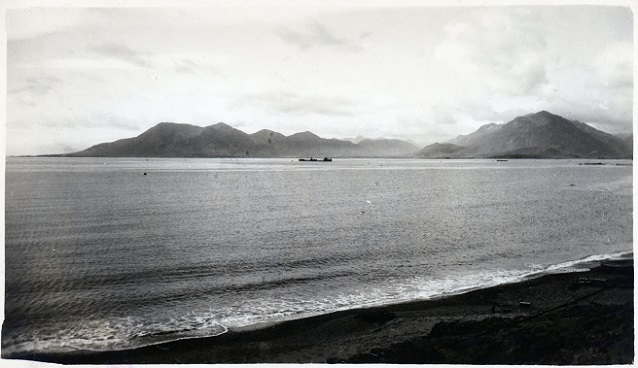

Photo courtesy of Walter Dalegowski

The weather proved reasonably good and we set our course directly for Attu. We arrived in mid February, working our way despite a storm and poor visibility into Massacre Bay. The storm was strong enough that there was no moving water traffic. With the exception of two freighters at the Army’s docks, all small vessels were either anchored or hanging to mooring buoys. Boredom got to Charlie our mate and the civilian chief and they decided to take our skiff with outboard motor and go into the beach. When they got at dockside the next day, they returned, and remarked that the shoreside people told them how foolish they were to have attempted running the bay in bad weather. Another sobering sight observed was what remained of the large barge high aground on a rocky reef, separated from shore at low tide. Seeing it sitting high and dry, one had to use imagination to picture in his mind the height and force of waves that could totally pick up this vessel and implant it above water. It gives you, the reader, a mind illustration of how much protection Massacre Bay did offer. We were also told of an ST (Small Tug) dragging anchor and beaching in the surf some distance from shore. The consequence was that all crew members were not able to make shoreside. There was a loss of life. As I recall hearing the engineer and one other were drowned.

Attu-Shemya Supply Line Ferrying Service

Attu, in February of 1944, was a well developed Army and Naval Base. In the nine months since the retaking of the island, many miles of roads had been built, fanning out from Massacre Bay, into the hills and along the beach. The main air strip was on the westerly side of the bay, along with naval installations, including two piers and a floating dry dock, which could offer repairs to their ships and on occasions Army vessels. As mentioned earlier the Army’s two docks were at the very head of the bay. On the southeasterly side entering the bay, the long sandspit called Alexi Point was the facility housing an Air Force P-38 group. At this time the Army was attempting to build a marine railway for hauling our Harbor Craft vessels ashore for repairs. Some how our crew lost count of how many times the project would be near to 50-60 percent complete, before a storm with high winds would topple it. Eventually, the task was abandoned.

Within a week following our arrival we began our basic job, joining the other power barges to supply Shemya which was intended to be a B-29 base to bombard Japan from the north. On our first trip we had aboard the former skipper of the BSP 873. He was to offer us his experience as having made the journey earlier, though how great his knowledge, is in question, as the belief is he probably only made one voyage before going aground. None the less, he knew more than we. Shemya lies about 25 miles east of Attu. It is one of a group of three islands, the others being Nizki and Alaid. The running time to Shemya was about 3 ½ hours. About half an hour after leaving Massacre Bay, Alaid, the most westerly of the island with a high rock promontory would come into view and directly behind it was Nizki and separated by a narrow channel lies Shemya. Our arrival brought us to another new experience. The island had no harbor or bay for protection. The dock to be sturdy enough to face the direct force of its northern exposure had pilings driven side by side. As you approach for mooring the common custom is to pass your main lines to the attendants ashore – not so in this operation. Light heaving lines were tossed aboard which after hauling in were attached to a steel cable, the cables in turn were hooked firmly to power winches on two bulldozers, one at our bow end, the other the stern. They proceeded to draw us in against the dock side (only one side was useable). Perhaps the only positive thing was that under us was a sand bottom. As we continually bounced off the bottom, a large force of port battalion workers would come aboard and rapidly unload our cargo. I do not believe that while these conditions existed, we ever spent more than 45 minutes tied up at Shemya. After the cargo was removed, the workers scrambled ashore, we would cast the cables off and stern first push our way to deeper water and head back for Attu. Weather permitting we would return tomorrow. The power barge fleet of perhaps fifteen were a never ending freight ferrying service.

Sometime in early April, while at dockside at Shemya we saw a freighter anchored offshore, a distance of approximately two miles, and as each power barge was offloaded it was instructed not to return to Attu but to prepare, each in its turn, to come alongside the freighter and carry its cargo to shore. This would save the time of a round trip to Attu and back. Early April is not truly spring in the Aleutians and storms are common occurrences, but never the less, with heavy seas running, two barges, one tied to each side of the freighter, we began the task. With bow and stern lines as thick as 3 inches and slightly smaller spring lines we attempted to hang on. At times a wave would carry us apart by maybe a distance of 10 feet, and the next would pick us up and pound us against the freighters side. Other times the heavy lines would suddenly part in a manner similar to breaking a piece of thread in your hands. This was a 24 hour operation, and at this time we still had our civilian skipper aboard, and each time we were to make the run from ship to the dock and vice versa he would awaken all hands. In a period of three days I do not believe anyone got more than one hours sleep at a time. Fortunately, he along with the civilian engineer returned to the states a week or so later. As time went on we used only four people per eight hour period and all aboard got a decent amount of rest. Proper sleeping ours on a ship can be dictated by the weather, and if caught on the sea in a storm, one would try to curl his toes under his mattress and at the other end grasp whatever was at hand. If you slept in an upper bunk you became more proficient than the fellow below you. This proficiency was gained in the knowledge you had four more feet to fall and it was simply a matter of hanging on extra tight.

Before the freighters[sic] unloading was completed a storm accompanied with snow came blowing out of the north. The initial response was to move out into deeper water, and then realizing there would be no abatement, head back to Attu and seek whatever protection Massacre Bay could offer. Simply speaking it was never that easy. There was little visibility in daylight and in darkness none at all. To get into Massacre Bay required seamanship of the first order and a great deal of good luck. Most barges and the freighter chose to keep away from any shore.

The BSP 1919 skippered by Sgt. Vincent Schoffmeister was low on fuel and had no choice but to return to Attu. For the first time radio contact came into being. The Shore Station US 3 phonetically called – Uncle Sugar Three – kept contact throughout that night with the BSP 1919 and as I remember Schoffmeister’s voice, he never sounded anything but calm and calculating. He somehow in that dark snowy night got past the rocky outcroppings at the mouth of the bay, through the sub net, and then once inside suffered the indignity of running around. All crew members got ashore safely, a credit to their efforts that night. The other ships were contacted, and the following day found them scattered about all points of the compass. The freighter was somewhere west of the waters between Attu and Agattu. We were north of Shemya. The BSP 1917 was off Chirikof Point on the north east side of Attu. I cannot recall the position of others, but with the storms passing, all found their way back to home port.

As spring progressed and early summer came on, the other freighters laid offshore of Shemya, sometimes two at once. The barge fleet working around the clock carried all kinds of supplies and equipment dockside. Bulldozers, Earthmovers, power shovels, pile drivers and Euclid trucks all were broken down into parts, carried ashore and reassembled. Soon the piledrivers were working to build two long docks (gossip said they would be the longest in the Alaska-Aleutians). As that work continued the shovels and bulldozers were hacking away at a high rock promontory and the Euclids carried the huge stones to two points to start the building of a breakwater that would offer the facility to bring these large freighters to shoreside docking, and the safety and protection, from the open seas.

Salvage Mission

About the middle of June we were selected to go to the South side of Agattu to salvage what remained of an FP Boat (Freight Passenger) that had run upon rocks while servicing a radar sight on the island. We took aboard two civilian divers and a on a rare blue sky day left Attu, rounded the west end of Agattu, cruised parallel with the south shore and entered a deeply indented unnamed cove with sheer cliffs, perhaps 150 feet high to port and starboard. At the end of the cove these walls gave way to a gravelly beach, and for guidance if you were to run your bow ashore for off loading, stood one solitary utility pole. As a reader you must at this time understand that the protection of wildlife did not seem as important as it does today and therefore, do not look upon us with bad feeling, as to some of the things we did. The left side wall of the cove was solid stone with many little shelves and ledges, and flying about it were a good number of sea birds, mostly puffins or as we called them sea parrots. Some one thought we might stimulate the birds by firing our ships one piece of armament – a 50 caliber machine gun- at the rock face. Little did we know that this was a nesting place and as the shot exploded on the cliff, hundreds of birds took to their wings. For all the noise and confusion, I doubt we did little damage, and they quietly settled back into their nesting routine. That evening, just before dark, silhouetted on the crest of the opposite wall of the cove I observed eight to twelve figures. They appeared to be persons standing. With binoculars I could identify them as eagles and in following days one would come and alight on the utility pole and observe use. He became fair game and often he was shot at, and one day he was killed while flying away from his perch on the pole. It seemed nothing at that time but we were contributing to the near extinction of the eagle in the western Aleutians.

The divers worked the wreck for perhaps a month and it appeared it was hardly worth the effort for they salvaged little of value and the ship was broken so badly below the water line it could not be raised. A couple of times we ran our bow up on the whore with supplies for the radar operating people and they would come down the hilly slope driving a four wheel drive ton and a half truck. On one occasion, a rare southwesterly storm drove heavy swells into the cove and forced us to leave. Someone suggested we explore by circumnavigating the island. We went eastward along the southshore, turned to port to view the east end and then ran along the Northshore where we were on the lee side of the storm. At one point we observed the double cross ties of the Russian Orthodox Church. We anchored and four of us went ashore. The beach was a gentle slope and a good distance along the shore was quite flat. We went to the cross site and speculated that some one was buried at its foot and further reconnoitering brought us to a true barabara, built mostly below ground. It probably was used up to the time of the war’s starting, as a couple of goose type heads laid on the roughly built table. Who ever occupied the dwelling did not do any housecleaning before he left. We did at one time or another see foxes of a bluish-gray color. To close on our Agattu adventure I would raise the question to someone knowledgeable of the island. As a schoolboy playing marbles, the smaller ones not made of glass were called agates. I do not know if Agat-Tu refers to a mineral or marble but in that unnamed cove the beach edge has millions of nearly round stones of the pale colors of red and blue. As the waves wash ashore they continually roll the stones giving them a polish of sorts, and at the same time the sound of this rolling affect.

Working for the Navy

Some time in July after returning to Attu we were assigned to the Navy. A task force was in the bay and our job was to supply them with rations for the journey to shell the Japanese, Kurile Island. Most often this force comprised of three cruisers and perhaps a dozen destroyers. They certainly had better food than we: fresh fruit and vegetables were unknown to us. We did take the liberty of opening the crates and taking some of this fresh fare, but never in an amount to be missed. I do think the naval lieutenant in charge of the operation suspected us of this, and perhaps the fact that we did not abuse the situation he looked the other way. Also, he was most considerate because on the final trip he would present us with some of these stores. The greatest gift was half a dozen honey dew melons.

During this same period of time the yacht Cavenaugh dropped anchor in Massacre Bay. The Aleutian issue of the Alaska Geographic refers to a soldier going to the Battle of Attu on a ship called the Cavena, which had a gold bath, a rose bath and innumerable luxurious features. It does appear he spelled the name as it sounded but I do believe the Cavenaugh and the Cavena were one and the same. This vessel was operated by a civilian compliment with the exception of a military gun crew and radio operator and was under contract to the Army Engineers. Its main duty was carrying civilian personnel from Seward to the Islands. The radio man aboard was Sgt. Jack Labreck, a high school classmate of mine and recently he passed on his knowledge of this vessel. It was 155 feet long with all the finer appointments of ship building and was constructed in Bath, Maine, probably in the 1930’s, for Henry Sorenson, an executive for Ford Motor Co. It was fitted with the most modern navigational equipment and while on the Aleutian run it added depth charges and a 3.5 millimeter gun on its stern. The gun if fired threw the vessel 90 degrees off course. The vessel had been built for use on the Great Lakes and instead of a keel had wash cocks and it consistently rolled even in perfectly calm seas. It had automatic steering that made constant compensations for steering a properly set course. It had a gyro compass that reacted to atmospheric pressure and was not effected [sic] by magnetism. Returning to the deck gun, it was of World War I vintage. It was fitted to have elevation, but with no control for traverse. On occasions when they had gun drill after releasing the traverse locking pin the barrel would spin around at point blank range be aimed at the pilot house. Labreck said they never loaded it and never fired it and never really knew how. Another experience he relates is that while on one trip a passenger passed away. He was rolled in canvas and lashed outside on the open deck. Some time later they sailed into heavy weather and the body broke loose from its tied position and was sliding up and down the deck. To compound the situation, the depth charges came loose from their ties. It was a harrowing time scrambling on decks awash to secure everything. It appears the explosives were of first concern, the body second.

Photo courtesy of Walter Dalegowski

During this same period of time the yacht Cavenaugh dropped anchor in Massacre Bay. The Aleutian issue of the Alaska Geographic refers to a soldier going to the Battle of Attu on a ship called the Cavena, which had a gold bath, a rose bath and innumerable luxurious features. It does appear he spelled the name as it sounded but I do believe the Cavenaugh and the Cavena were one and the same. This vessel was operated by a civilian compliment with the exception of a military gun crew and radio operator and was under contract to the Army Engineers. Its main duty was carrying civilian personnel from Seward to the Islands. The radio man aboard was Sgt. Jack Labreck, a high school classmate of mine and recently he passed on his knowledge of this vessel. It was 155 feet long with all the finer appointments of ship building and was constructed in Bath, Maine, probably in the 1930’s, for Henry Sorenson, an executive for Ford Motor Co. It was fitted with the most modern navigational equipment and while on the Aleutian run it added depth charges and a 3.5 millimeter gun on its stern. The gun if fired threw the vessel 90 degrees off course. The vessel had been built for use on the Great Lakes and instead of a keel had wash cocks and it consistently rolled even in perfectly calm seas. It had automatic steering that made constant compensations for steering a properly set course. It had a gyro compass that reacted to atmospheric pressure and was not effected [sic] by magnetism. Returning to the deck gun, it was of World War I vintage. It was fitted to have elevation, but with no control for traverse. On occasions when they had gun drill after releasing the traverse locking pin the barrel would spin around at point blank range be aimed at the pilot house. Labreck said they never loaded it and never fired it and never really knew how. Another experience he relates is that while on one trip a passenger passed away. He was rolled in canvas and lashed outside on the open deck. Some time later they sailed into heavy weather and the body broke loose from its tied position and was sliding up and down the deck. To compound the situation, the depth charges came loose from their ties. It was a harrowing time scrambling on decks awash to secure everything. It appears the explosives were of first concern, the body second.

Summer- Dangerous Cargo and Pranks

Once again we commenced carrying cargo to Shemya. One load consisted of dynamite and the exploding caps. Maritime Law does not allow a ship to carry both but the Army did not recognize the law of the sea during wartime. We carried a full deck load of canvas covered dynamite with the caps stowed in the food locker. Neither were more than 10 feet apart. It was with a sign of relief when it was removed at Shemya. Another occasion found us carrying an Army light tank. I say light because it was quite small. It was tied down in a manner that seemed secure. But in rolling swells it broke loose abreast of Alaid Island. The brakes were not set and with each pitch and roll of the ship it would run to the lower side of the deck. It would seem that in a matter of time it would smash through the bin board side rails. From our viewing post in the pilot house we were sure at any moment we would lose it, but for all its erratic movement it stayed aboard until we docked at Shemya. Another trip found us with a load of 75 pound bags of cement. Though covered with a canvas tarpaulin many bags became wet and broken and after removal we hosed the deck and side walls of the bin boards to wash it off but a good amount had set and remained encrusted as long as I was aboard.

[p]Summer in the Aleutians is for the most part a period of fog but there were times of blue skies and sunshine. On one such day, we watched about twenty five YMS (Yard Mine Sweepers) ships pass in a single column – all flying the red hammer and sickle flag of Russia. They were American built and part of this country’s lend-lease plan. Whether this was a training mission or a show of force to remind us that they too were operating in the North Pacific, I do not know.

These infrequent beautiful summer days seemed to bring out the best in men. Though a war was still in progress, humor and horse play were not out of order. Flying crews both Army and Navy with visions of aspiring to become the likes of General Doolittle, Chennault or Admiral Nimtz took to the air. Their mission: to scare the hell out of our barge people. One afternoon after arising from my bunk following my night watch (12 am to 8 am) I was taken outside so I might see the effects of a B-25 that buzzed us earlier in the day. It had taken three feet off the top of our mast. This may not appear of any great consequence but the point of impact was probably only thirty five feet above the sea and perhaps ten to twelve feet above the crew members in their pilot house at that time.

Sometime later on another clear afternoon we were about equal distance between Attu and Shemya. In the pilot house sitting on a stool holding the ships wheel was our mate, an Alaskan native Robert (Shorty) Roberts; Tex a deckhand stood in front of an open window and I laid on a chart rack behind them. Off toward Shemya, maybe ten miles away, a PBY was just above water level and as the distance grew shorter there was no doubt of their intentions. They were about to give us the full treatment. It is strange how each person sees another react, but not himself. Shorty at the wheel was rocking on his stool moving the wheel slightly to the left and right. Tex was shouting a few choice GI curses and I jumped off the chart rack and ran to the back of the ship. I recall thinking if he hits us, it’s only twenty five feet from the point of impact, it makes no difference. I dashed back to the pilot house. About now you could see figures in the cockpit. Shorty was still rocking on his stool and I think trying to talk but only a grunting sound came from his mouth. The Texan had opened the pilot house door on the starboard side but his body was only half out. I stood behind Shorty and looked eyeball to eyeball at the PBY. He appeared to just be hanging in front of our bow. I said to Shorty, “He will never be able to pull up in time.” I believe my voice showed total panic. It appeared he just sort of hung in front of us with a slow- oh so slow- uplift carried over. The Texan said he could see their grins as he shook his fist at them. Fortunately, this was our last exposure to summer fun and frivolity.

The Aleutians lying approximately along the 54th degree of latitude makes for long summer evenings with daylight extending into the ten o’clock hour. On the few clear evenings that did occur regardless of war there was a good feeling that is difficult to explain. Perhaps it was due to the calm seas (even with fog) warmer weather and winter still seeming far away. Though still carrying cargo from freighters standing off Shemya, the pace was more relaxed. Each day the heavy trucks dropped more rocking extending the two sea walls that eventually would create a man made harbor. Going ashore one day I watched as asphalt was being laid for hard surfaced runways. A B24 came into land on the original steel matted strip braking as it rolled – its nose nearly touching the ground upon each application of the brakes – the pilots intent not to carry to[sic] far forward onto the hot asphalt.

Everywhere progress was taking place. The easy living allowed time for tying alongside another barge. The deck of cards were taken out and on occasions the poker game went into the weehours[sic] of the morning or more quickly if someone was on a winning streak. On one such evening a group of P 40’s buzzed low, went aloft to loop and roll and then dropped over the ships at a slow speed that appeared to be a crawl, wiggled and dipped their wings. As all this unfolded before the eyes, one had to have a feeling of pride to be part of such a mighty effort of men who were to overcome the many pitfalls of this storm and foggy chain of islands.

Aside from the joy of summer and the massive construction taking place I expect everyone had a sentimental reminiscing time. One afternoon a storm came out of the northwest. Usually at this time of year they lasted but a few hours and this one did likewise, but because of it, we went through a narrow pass between Shemya and Nizki. It was so narrow, one might refer to it as a channel and it had only been in use a short time. I do not know what barge or tug was the first to pass through it but on this occasion we did use it to go to the leeside of Shemya to avoid the storm. By evening the wind had subsided and all that remained was a gently rolling swell and the 1923 rocked easily at anchor. I was the single night watch and in the pilot house, I searched the radio dial for music. From somewhere, Seattle, San Francisco or Hawaii Dinah Shore sang “I Walk Alone.” Sitting there in the dark how easy it was to dream – dreaming of all the happy times if you could be back in Massachusetts.

"Liberating" Sardines and Beer

In the course of ship to shore cartage we often watched the various items being loaded. All boxes were coded by color and we quickly became astute in recognizing PX supplies, various foodstuff and beer. The word liberate refers to the freeing of someone or something. All sorts of boxes liberated a case of Parker 51 Pens, a case of Zippo lighters, wristwatches, coffee and even sardines. I was a party to the sardine theft. Actually, I did not care for them that much, but what desire I did have for them evaporated upon opening the first tin. Much to my horror they were not sardines but anchovies. At that time few, if any, of our crew had eaten them before and after tasting this heavily salted pinkish-brown fish no one wanted any part of them. Eventually, a fellow townsman from Massachusetts serving in a coastal artillery battalion at Attu came by and was asked if he cared for anchovies. His response was “I love them.” Needless to say he walked off the boat overwhelmed by our generosity.

Beer was naturally the biggest prize one could liberate. At that time our ration was one case of beer per man per month. Ashore and on some ships enterprising people were running off some decent high potency flavored alcohol that was started with grape jelly. The Army, for whatever reason, never had any other kind. If you had fifty dollars one could purchase bonafide low price whiskey – Schneley, Fleishmann and Seagrams 7 – from freighters up from the states and other smaller boats that occasionally came from Seward or Kodiak. Under these conditions any barge carrying beer had to take advantage of such good fortunes. I would guess that every power barge serving the Attu-Shemya Islands did at sometime[sic] liberate various amounts of beer. The record haul was 100 cases, taken by one barge. This was a monumental fete at the time. They were loaded from a freighter, no more than two miles offshore of Shemya. After casting of their lines and running at slow speed the time to the dock could reasonably be no more than thirty minutes. With a crew of nine, one man had to be at the ships wheel and the other eight working to remove the beer case by case from the cargo deck to a safe hiding place. You may ask if the authorities were aware of the theft and searched the ship, how could they not find these cases of Rainier and Sick’s Select. American ingenuity surpasses everything. Now the secret can be told. In the engine room were ballast tanks. Sometimes fuel oil was carried in them and sometimes water. Each tank had a bolted cover and gasket. If the bolts were unscrewed and the cover removed a man could crawl through. This was there the booty was stowed and then the tanks were flooded with water. One barge reported that an M.P. (Military Police) search team did loosen a couple of bolts but when water seeped out gave up on that idea. Like everything else all good things must come to an end and when the Catholic Chaplins wine was stolen the higher authorities were really incensed. From that time on an M.P. was aboard for every trip from ship to shore and future piracy was negligible.

Autumn- a Rough Thanksgiving and Some Gambling Luck

The summer season now passed in to Autumn and the Attu-Shemya shuttle moved at a slower pace. At Shemya the breakwaters had been completed and two large piers were in place (it was said at a cost of fifty million dollars). Runways were all hard surfaced, waiting for the arrivals of the new massive B-29’s, which would ultimately bomb Tokyo and the Japanese industrial cities. This never occurred: with the dropping of the two atomic bombs the war came to an end and not a single B-29 bomb squadron ever came to Shemya. At one time in the summer, Tokyo Rose mentioned that a factory of some sort was in operation at Shemya. I could only guess that a Jap submarine laying off shore could see the cloud of smoke and fire blowing out of the stack of the Asphalt plant.

The day before Thanksgiving 1945, we were ordered to carry a group of civilian workers to Shemya. Our skipper informed the commanding officer that under no condition would we leave until the holiday turkey had been brought aboard. How silly it seems now but at the time it was a monumental struggle; one lowly boat crew fighting the higher echelon. At sword’s point and with some earthy GI phases[sic] thrown in little David overcame Goliath. The turkey and fixing came aboard. The civilian workers, approximately sixty, came aboard and off we sailed to Shemya. Shortly after rounding Alexi Point and into open water, we were into a decent storm with some choppy seas running. As we continued on, the winds increased and the seas became heavier, and though our crew could handle the situation, the same was not so for the civilians. Most of them started out standing on the open deck, but in quick time they sought whatever shelter they could find. Our galley-salon was overflowing with most men standing. The available seating had long since been taken. They invaded our sleeping quarters – some were deathly sea sick. One person was in the Ship’s Mate Charlie Hines’ bunk holding a peanut can (a can to catch his innard[sic], which it appeared were about to come out at any moment). Charlie was off watch and told the poor soul to remove himself. In sheer desperation he made a bonafide offer to lease the bunk for the sum of twenty dollars for the duration of the trip. The monetary presention[sic] was turned down, as sorrowful as it was, and he was evicted. After about 2 ½ hours of pitching and tossing we came abreast of the westerly end of the Alaid Island and through the wind driven rain from a distance of perhaps eight miles we saw a light signal coming from Shemya. Though difficult to read, the message was repeated a number of times. We were told to turn about and return to Attu. By now we were in a true Aleutian blow, but without mishap we came dockside at about eight that evening. One must remember, these solid ground people had now been subjected to about six hours of grueling punishment. As we touched the pilings one fellow asked, “Is this Shemya?” The reply was no, we had to turn back to Attu. A question remains, did that fellow take a second trip? By coincidence, a cargo net was hanging off the dock and our passengers pounced upon it with a vengeance and sick as they were, they scrambled ashore, true veterans of Aleutians weather.

The following morning news passed quickly from boat to boat. The storm, the first big one since summer, had devastated Shemya harbor. The two breakwaters had for the most part been washed away. Half the lenghth[sic] of two docks were no more than driftwood in the Bering Sea. What, for all appearances, was to offer shelter from the winter siege of weather, was taken from us in a few short hours. Though conditions at Shemya were not good, they were still better than when we arrived in February of 1944. We were not committed to daily runs as before, perhaps, because of the great supply of stores that landed in the previous summer and maybe it was the capability of more air freight, with paved runways, the installation of landing lights and increasing perfection of radar.

About this time our present cook, George “Rabbit” Daniels, was notified he was to be rotated back to the states. I spoke of him earlier and of his compulsive gambling. He had had poor gambling success in these months but unknowingly lady luck was again to smile upon him. He went ashore at Attu after receiving his pay and proceeded to the monthly big game. Thousands of dollars would change hands that night. He returned in about four hours and the first question asked him was how much he had lost. We should have been a little more observant. He was not to[sic] steady on his feet and had a smirk on his face. It appeared he had celebrated with a few snorts of some ones [sic] tent made fruit flavored alcohol. We assisted him aboard and sitting him down we went through his pockets. After a total count of all denominations, it appeared he had won approximately $1,300.00. The following night, his confidence at the highest, he made ready to go ashore for some more rolling of the ivory cubes. Charlie, the skipper, insisted he only take a small amount of money, perhaps no more than two hundred dollars. Most agreeable, he departed. Within a little more than two hours he shouted for the ladder to be laid to the dock. After crossing and coming inside he put his winning son the table – a tidy sum of approximately seven hundred dollars. Shortly after that he left us and went home on leave. I think the entire crew was happy for him. He must have been overflowing with joy. After serving nearly 2 ½ years in the Alaska-Aleutians he was going home to see his family and the feeling of security with two thousand dollars in his pocket.

Photo courtesy of Walter Dalegowski

Winter Routine & a New Job

The winter passed by seemingly uneventful. Things became quite routine. In early April, I received orders to proceed to Anchorage to attend radio school. This would be my parting as a crew member of the 1923. Though wanting to go, there were still moments of misgiving. Through these months some of us had built up a fellowship akin to brotherhood which continues to this day. It was not especially easy to depart, to lead the much easier life in Anchorage, knowing that there were still hardships they would endure. All the same one could not pass by such an opportunity. Thusly, with Warren Spencer of the BSP 1920 I went ashore. We were quartered in a Quonset hut about five miles up in hills and on three occasions alerted to proceed to the airfield for our flight. Three times we made this trip by truck, only after waiting many hours, to be informed that due to poor weather nothing was flying. After these three dry runs, Spencer and I agreed that the next time we were called to go, that regardless of weather we would remain at the small operation building at the edge of the runway. We had not long to wait as at noon we were ordered to be ready. Throughout the afternoon and evening the snow was falling heavily. We poured ourselves out on the wooden benches and got what sleep a hard surface offered. About two in the morning we were shaken awake. An ATC (Army Transport Command) C-47 had just landed and would shortly be leaving. Picking up our A & B Bags we went outside. The snow storm was still going strong. Visibility was next to nothing. How they got into Attu we could not understand but here they were and we got aboard. The engines roared and we were on our way. Awaking some hours later, we landed at Anchitka[sic], more people came aboard and we were off to Anchorage though we stopped once more for refueling at Naknek.

From Anchorage I made one trip to Adak as a radioman for the FS 243, and then I was assigned as a member of the Shore Radio Station at Seward – call letter WLQF – phonetically William Love Queen Fox, and one day in the fall of 1945 I received the call of the BSP 1923 which had entered Ressurection[sic] Bay and was now tying up in the small boat harbor. Stepping outside and looking over the roof of a warehouse dock was the mast of a vessel, short by three feet. It now housed a civilian crew and they never fully appreciated my relating the episode of the B-25 buzzing on a beautiful summer day in the Aleutians.

General speaking, this ended the cruise of the BSP 1923 from the military standpoint. Many of the tugs, freight passenger boats and barges were eventually sold off as surplus. Most recently I received a photograph of a barge at dockside in Seldovia. No doubt a few such vessels are, after nearly forty years, still in operation and they could each tell of events in the Aleutians long years ago. The Cruise of the BSP 1923 is only one of such stories. There are hundreds more that yet may be told.

Last updated: August 11, 2020