New research connects air quality to human experience in more than 1,000 different ways.

Article

Air Quality and Ecosystem Services

Photo by Martin Hutten

Ecosystem Services

National parks preserve some of the United States’ most treasured natural areas, from alpine lakes and breathtaking views to pristine meadows and natural sounds. We preserve these spaces to inspire current and future generations, and we call the benefits that people gain from natural systems "ecosystem services." These benefits range from inspiration for artists, fish for food or recreation, and clean water for future public use.

Human activities affect the quality of our land, air, and water, both directly and indirectly. Understanding how visitors use nature’s benefits both when they are visiting and when they go home, allows us to better understand the range of impacts that occur after a management or policy action, or when an external threat damages park resources. As the consequences of these developments are becoming clearer, land managers, policy makers, and researchers work together to balance the impacts with societal needs. It allows us to not pit man vs nature, but collaborate on decisions that allow for growth and conservation to take place simultaneously. This allows us to make more informed choices about our actions by balancing the tradeoffs of our decisions.

National Park Service leads the way

The NPS led a multiagency group workgroup to understand how the natural benefits of National Parks and surrounding U.S. Forest Service lands are being impacted by air pollution from human activities. Industrialization and urbanization have led to unprecedented innovation and development. As a society, we’ve enjoyed distinct benefits from these breakthroughs in technology, such as increased energy availability, food supply, and quality of life. At the same time, the major societal shifts have also caused some serious damage to human and ecosystem health: decreased air quality, polluted waterways, and loss of plant and animal species.

For example, rain or snow picks up pollutants from the air and deposits them into local waterways, resulting in acidified lakes and streams which cannot support fish or other sensitive species. Burning fossil fuels increases the amount of nitrogen in the air, which can increase the spread of invasive grasses through inadvertent fertilization. As these examples show, sources of air pollution can occur far outside a park’s boundaries but still travel with the wind and breeze past park entrance stations without paying a fee.

Monitoring a changing environment

The reason that the NPS and other federal agencies are interested in this is that we are witnessing changes occurring to some of our most sensitive resources, but they are not always relatable to the average visitor. By tying these changes to public values, it helps park visitors and others dependent on healthy park ecosystems understand how small changes to the air, water, and wildlife within the park, affect human quality of life directly and indirectly.

Scientists can use the natural laboratory of the National Park System to monitor changes in air quality. Scientists generally rely on biological indicators—plants or animals vulnerable to a specific pollutant—to signal ecosystem conditions are changing. But these biological indicators are usually non-descript or non-charismatic species (think tiny invertebrates rather than majestic bison) that fail to spur public interest or policy consideration. That’s why we developed a new way to show the effects of a changing ecosystem. It’s called STEPS.

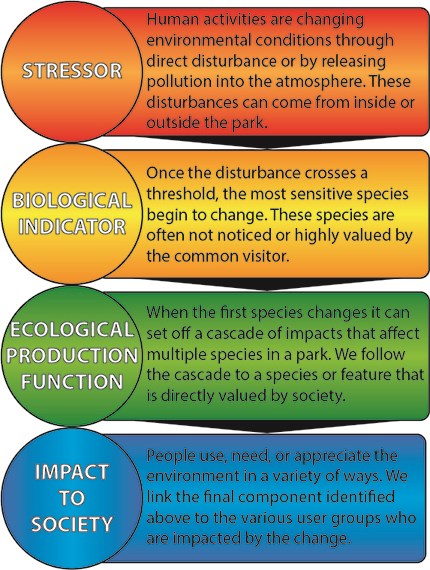

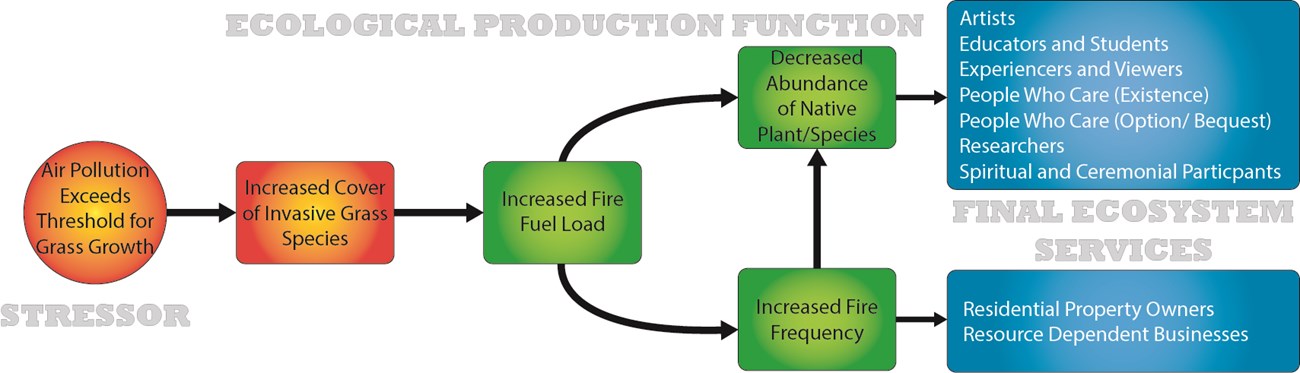

The STEPS (STressor – Ecological Production function – final ecosystem Services) Framework (Bell et al. 2017) links the indirect effects of human activities (i.e. excessive fertilizer) to direct effects on society (i.e. higher risk of wildfire) through a series of closely related steps. These “chains” follow the chemical and biological pathways from a change in a biological indicator to an ecosystem component that is directly used, appreciated, or valued by humans. Then, we can link the last link in the chain (or ecological endpoint) to its direct users, who are best equipped to evaluate potential changes.

For example, nitrogen pollution blowing in from Los Angeles acts like fertilizer raining down out of the sky in Joshua Tree National Park. In your lawn and garden, fertilizer causes plants to grow lush and green. In this desert ecosystem, nitrogen can cause invasive grasses such as Mediterranean split grass and red brome populations to increase exponentially in what were previously pristine wildflower displays. When invasive grasses grow dense, they not only outcompete native wildflowers, but also can now carry fire across some parts of the landscape which can perpetuate the cycle and make fires a common occurrence in these areas where they used to be rare. Not only does this impact park wildlife, visitors looking for flowers, local businesses dependent on tourists, but also homeowners outside of the park, as fires can spread far across the landscape.

Benefits of STEPS

This framework transforms complex environmental relationships into an easy-to-follow chain of events for public understanding and education. People become more aware of the true impacts of human actions on natural areas, and STEPS provides a framework to show different groups how they may be affected. Additionally, this process groups different stakeholders together who are affected by certain changes. The framework also lumps changes that a particular stakeholder should be interested in, giving that individual or group a comprehensive list of potential concerns. This inclusive list can guide decision-making, future research, management actions, and/or valuation. In addition, STEPS identifies stakeholders who may have previously been left out of a decision-making process because their interests aren’t directly affected by a change. The process helps show how many groups are tied together by otherwise unseen changes to the world.

STEPS in action

So far, we’ve used the framework to evaluate four different responses to air pollution via 1104 different chains or pathways:

- effects of nutrient enrichment on terrestrial systems (Clark et al. 2017)

- effects of nutrient enrichment on aquatic systems (Rhodes et al. 2017)

- effects of acidification on terrestrial systems (Irvine et al. 2017)

- effects of acidification on aquatic systems (O’Dea et al. 2017)

Each of these four analyses shows how the multiple benefits that people get from nature can be impacted when air pollution enters the picture. Sensitive ecosystem components are living things often overlooked by the average visitor (diatoms in lakes, invasive grasses, invertebrates in streams) but linked to desirable experiences for visitors in parks, such as clear water in lakes, wildflowers, and trout on the end of their fishing poles, and beyond parks, such as clean water flowing from parks into cities, and revenue from tourism. Showing a direct route from a preventable cause to an undesirable outcome highlights the interdependence between humans and services that nature provides for free; for visitors to parks, for people connected to the natural condition of resources in parks, and for future generations.

Download the NPS Resource Brief on Air Quality and Ecosystem Services.

Contact the NPS Air Resources Division for more information.

Last updated: October 23, 2017