When Abraham Lincoln was inaugurated as President of the United States on March 4, 1861, secession was an accomplished fact. The lower South had withdrawn from the Union and set up a rival government. The guns roared first at Fort Sumter, turning back Lincoln's relief expedition. Both sides called for troops, more Southern states seceded, and the nation plunged headlong into civil war.

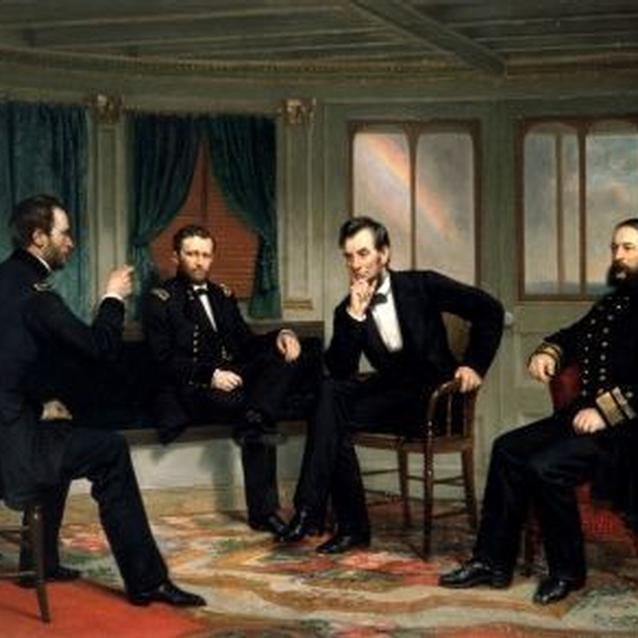

Library of Congress

The war went badly at first for the North. Plagued by poor generalship, the Federal army in the Eastern Theater was soundly trounced in 1861 and through most of 1862. George B. McClellan's repulse of Robert E. Lee at Antietam Creek was the solitary bright spot. After Antietam, President Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation, declaring all slaves in rebel territory free, but words could not substitute for victories. In December of 1862 the North suffered a crushing defeat at Fredericksburg, and in May of 1863 the Army of the Potomac became desperately unnerved at Chancellorsville. Lee now felt it appropriate to once again advance into the North in an attempt to destroy Lincoln's army on Northern soil.

In July the armies clashed at Gettysburg, and Lee was forced to retreat with bloody losses. As the North rejoiced, more good news came from the West. Stubby, soft-spoken Ulysses S. Grant had captured the strategic citadel of Vicksburg, splitting the Confederacy in two along the Mississippi River. Grant then proceeded to break the Siege of Chattanooga two months later, and a grateful Lincoln brought him east to command all the Union armies.

In May 1864, Grant ordered William T. Sherman and his force to set out across Georgia, while he himself advanced southward with the Army of the Potomac. Grant's plan was to consistently hammer away at Lee's army, for he understood that while the North could replenish the casualties with new troops, the South did not have the manpower to do so. Yet Lee fought desperately in the Wilderness and at Spotsylvania, and the casualties mounted. Suddenly Grant's aspirations for quick victory seemed as far away as ever. The two armies eventually settled into siege lines around the rail hub of Petersburg, Virginia.

White House Historical Association

The summer of 1864 was one of Lincoln's most difficult. Peace negotiations were begun, but had fallen through. With Grant stalemated around Petersburg, and no word from Sherman in Georgia, Lincoln soon came to believe that he had no chance of winning reelection. Yet the tide was slowly turning in Lincoln's favor. Two days after the Democrats nominated George B. McClellan for the presidency, Atlanta fell to Sherman and Northern morale soared. Lincoln won the November election easily, carrying 22 of the 25 participating States. The war was fast drawing to a close as Lincoln began his second term.

Lincoln's main concern now was the reconciliation of the country. In his inaugural address he described the war as a visitation from God and, mellowed and deepened by the ordeal, he pleaded for peace without malice. On April 9 Lee surrendered to Grant at Appomattox Court House. Two nights later a torchlight procession called at the White House.

Instead of a victory speech, Lincoln gave them his moderate views on reconstruction. It was the last public address of a compassionate man. On April 14 he and Mrs. Lincoln went to the theater. During the third act an assassin slipped into the Lincoln's box, shot the President in the head, leaped onto the stage before a startled audience, and fled into the darkness. Soldiers carried the slumped figure across the street to a boardinghouse and laid him across a bed. Surgeons worked over Lincoln all night, but he never regained consciousness. The next morning death came to the man whom power had ennobled.

Tags

- antietam national battlefield

- appomattox court house national historical park

- ford's theatre national historic site

- fredericksburg & spotsylvania national military park

- gettysburg national military park

- lincoln home national historic site

- petersburg national battlefield

- vicksburg national military park

- military

Last updated: February 4, 2015