Last updated: March 2, 2022

Article

A Community Speaks, and the National Park Service Listens

It’s about listening.

Before Katahdin Woods and Waters National Monument in Maine was created in 2016, its 87,500 acres of dense forest were all in private hands. Generations of local people had made their living and spent their lives in these north woods; logging, working in the mills, hunting and fishing.

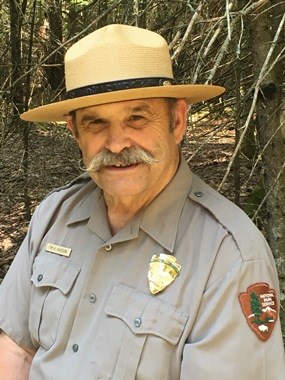

On the eve of the National Park Service’s centennial, President Barack Obama proclaimed the Katahdin Woods and Waters National Monument. Working with Superintendent Tim Hudson, the National Park Service’s Rivers, Trails and Conservation Assistance Program stepped up to help the new monument become a part of the community from the very beginning. Julie Isbill and Burnham Martin, Park Service project specialists out of Brunswick, Maine, came on board.

Building Trust and Connections

Isbill helped launch the Katahdin Learning Project, a place-based initiative that supports two local teachers by involving students in hands-on projects in the community and in the monument.

“We realized what we needed was teachers on the ground to help us do this,” Isbill said. “To build trust and connections. We wanted people who were right there, living there.”

“What we wanted to find out is how people use the land, what they saw as their favorite spots, how they access it, and how to blend that in to protect the resource but have the most diverse operation that you can get.” – Superintendent Tim Hudson

With community partners, the Katahdin Learning Project has sponsored cross-country ski outings to the monument, trail clearing, and other place-based learning activities, where students get out of the classroom.

Building Bridges

“We live in a very rural area but we don’t always take advantage of what’s in our backyard,” said Scarlet McAvoy, an elementary school teacher who participated. “The cross-country skiing was fantastic. It gave the kids a taste of something they may not have experienced.”

“Not many students had been in the monument,” said Kala Rush, a high school teacher. “Their parents and grandparents, maybe, had grown up in that area; fishing, hunting, ATVs, snowmobiling. These kids really didn’t know where they stood with the monument but this provided the connection. They actually felt like they were getting out and learning about their community and their area.”

The implementation of the Katahdin Learning Project is now led by the Friends of Katahdin Woods and Waters, a citizen conservation nonprofit organization. That is typical of how the National Park Service – Rivers, Trails and Conservation Assistance Program works. It builds partnerships and helps coordinate community conservation projects, then steps back to let others take over.

Empowering a Community

Andy Bossie, executive director of the Friends of Katahdin Woods and Waters, grew up an hour north of the monument; hunting, fishing, and snowmobiling in Maine’s wilderness.

The mission of Friends of Katahdin Woods and Waters is to preserve and protect the outstanding natural beauty, ecological vitality and distinctive cultural resources of Katahdin Woods and Waters National Monument and surrounding communities for the inspiration and enjoyment of all generations.

“Not only does our mission include the monument, but supporting and uplifting the community, the Katahdin region,” Bossie said. “We’ve got a better tomorrow to make. The monument is here. I think people are interested in how that is going to better their tomorrow.”

An oral history project was another bridge to the community. The National Park Service co-leads the Katahdin Story Booth with the Millinocket Memorial Library and the Maine Folklife Center.

The project began when Matt DeLaney, director of the library, met Isbill at a community meeting and realized they were both independently thinking of an oral history project.

“I’d never heard of the Rivers, Trails and Conservation Assistance Program,” DeLaney said. “I had no idea what they did. Julie [Isbill] was amazing to work with. Without her, this project would not have happened. They were just making sure it all moved forward. Navigating political issues, communicating, she was great.”

Telling the Stories

For the oral history project to succeed, it quickly became clear that they needed to broaden the focus and not make it solely about the new monument.

“Our community is going through a pretty radical transition from an old industrial-based economy to something a little less certain going forward,” said DeLaney. “We asked people to tell us their personal stories.”

Many of the interviews took place at the library, an inviting space that lends itself to telling stories and sharing memories.

“Each interview is unique,” said Isbill. “Talk about yourself and your relationship to this region, whatever that may be. What does the greater Katahdin Region mean to you?”

The Maine Folklife Center has a 60-year history of doing oral-history research. They provided technical expertise, some training and funding.

Ettenger built a mobile recording studio in an R.V. to take the project further. Under his direction, 10 students from the university have created short podcasts from some of the material collected.

“If the story of this region is to be told, or the story of the monument, it should be told by the people who live there,” said Ettenger.

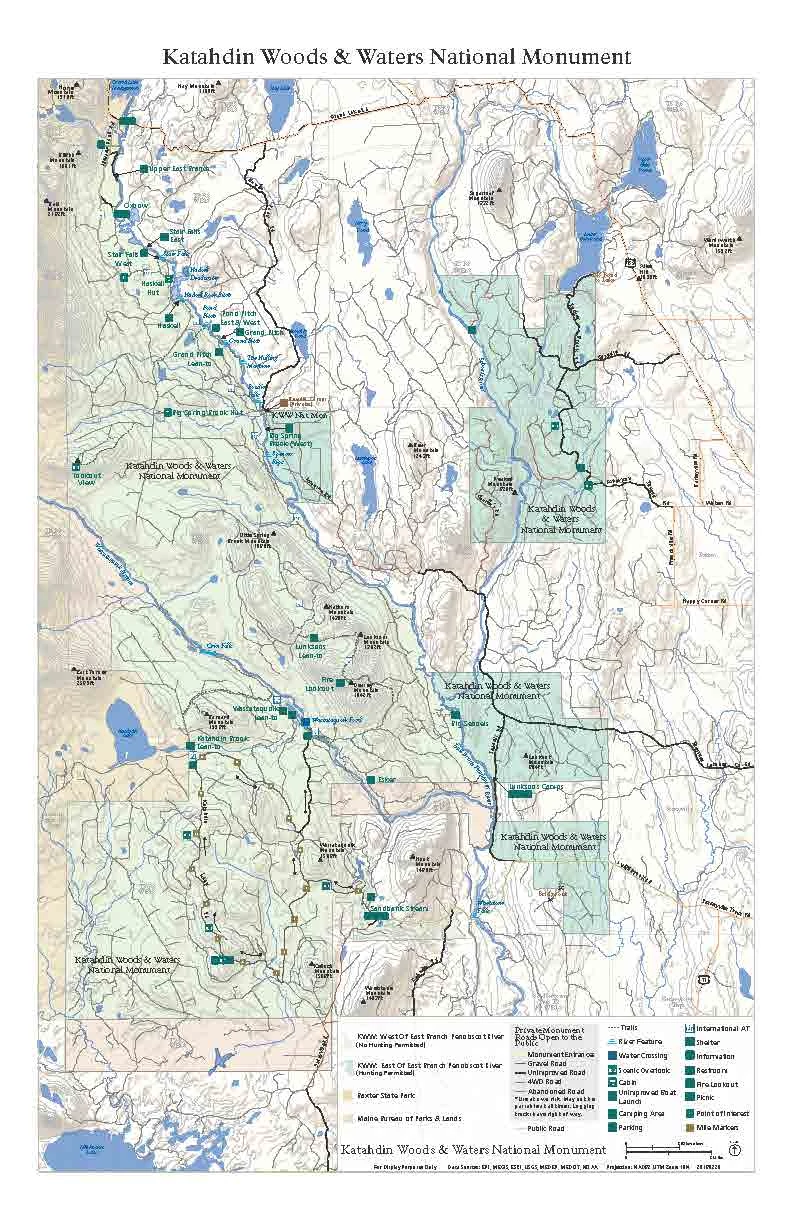

Establishing Access to the National Monument

Inside the monument boundaries, the National Park Service was active on other projects. Working with monument staff and volunteers, Burnham Martin helped create a wayfinding sign plan and field map, conducted a trails inventory, and mapped several potential new trails in the monument.

“The woods there are laced with old timber roads and skid roads,” said Martin. “It was very confusing. We needed to inventory the road system and look for places where people might get lost.”

Martin attended the listening sessions early on and said that building relationships was key.

“We innately see the value of these connections between nonprofits and communities and the monument,” Martin said. “It’s in our blood to facilitate and improve those connections. I would add that Tim [Hudson] really seems to get that. I’ve had the pleasure of driving around with him to go and do something on the monument and it takes twice as long because he keeps stopping to check in with local people. He goes to check on one thing and ends up having a long conversation, and that’s how you build relationships in a rural place.”

The superintendent, whose career with the National Park Service goes back to the 1960s, considers connecting with the Katahdin community as much a part of his job as putting on his hat.

“You need to go talk to people,” Hudson said. “It’s typical in rural communities. You need to spend the time and get to know ‘em. You learn, you always learn.”

Story by Laura Watt