World War II and Reclamation in the Post-War Years

The Great Depression paved the way for some of Reclamation’s greatest achievements as New Deal dollars flowed to the Bureau of Reclamation. On the Columbia River in Washington State, work began in 1933 on Grand Coulee Dam, one of the largest concrete structures ever built. Plans called for two hydroelectric powerplants – each to house nine of the largest generators ever constructed at the time. By April 1942, however, with America recently entered into World War II, only three of the eighteen generators were online.

The nation desperately needed Grand Coulee’s generators to help produce the unprecedented amount of electrical power needed to make aluminum, used in the building of warplanes and ships. That same year of 1942, the President had set a goal of 60,000 new planes, a goal that would require 8.5 billion kilowatt hours of electric power. When wartime shortages prevented the delivery of additional generators to Grand Coulee Dam, the Federal government turned to Reclamation’s Shasta Dam , still under construction in northern California. Two of Shasta’s 75,000 kilowatt generators, sitting in storage, were hauled to Washington and installed at Grand Coulee instead. The first unit from Shasta went into service at Grand Coulee Dam on February 25, 1943, followed by the second unit on May 7.

By 1944, Bureau of Reclamation powerplants in the West had quadrupled their hydroelectric power output. By war’s end the following year, Reclamation powerplants had produced 47 billion kilowatt hours of electricity, enough to make 69,000 airplanes, 7 million aircraft bombs, 5,000 ships, 5,000 tanks, 79,000 machine guns, and 31 million shells. Electric power generated at Grand Coulee was so important to the war effort that its power accounted for as much as one-third of the aluminum used in aircraft during World War II. It was power from Grand Coulee, as well, that charged reactors at the nearby, top-secret Hanford Site, which figured prominently in the making of plutonium supplied to Los Alamos for the atomic bomb.

As hundreds of thousands of people moved west in the 1940s to work in the war industries, cities grew, especially in the three Pacific Coast states, where population mushroomed by a third between 1940 and 1945. With the end of the war, surplus electricity from Federal powerplants was put to use in rapidly developing peacetime industries. Industrialist Henry J. Kaiser, for instance, turned a wartime aluminum plant into Kaiser Aluminum’s Trentwood plant, which continues today to employ people in the Spokane Valley of Washington.

The Post-war West

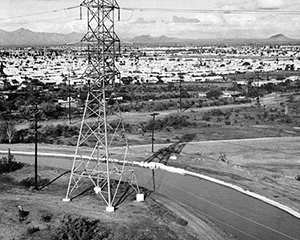

As cities grew and modernization accelerated after World War II, Reclamation’s customers grew increasingly urban and its hydropower services tied more and more to municipalities and industry. Vast new suburbs and low, post-war utility rates created an ever-growing market for electricity in the years 1945 to 1965. Electricity no longer was a mysterious luxury, but something Americans expected at the flip of a switch. To feed the growing demand, 13,000 miles of transmission lines were laid during the Truman presidency alone; this added to the 11,000 miles strung during all previous administrations.

During the Eisenhower years, new powerplants fueled by hydro, steam, coal, and natural gas came online, as well as the world’s first nuclear powerplants. Reclamation embarked on a post-war building boom as Americans embraced new technologies, such as air conditioning, which created an enormous increase in demand for electricity.

Integration of the Public and Private Systems

In the 1960s, private utilities in the American West found it economical to integrate their production and distribution systems with those of the Federal Government. The importance of a better-integrated transmission system was underscored in November 1965 when a single electrical surge toppled the power grid in the Northeast. The blackout, famous for stranding people in New York City elevators and subway cars for hours, left some 30 million people in the dark all across the Northeast and into Canada.

Initial Federal efforts to integrate the West’s transmission system occurred in the 1930s when Reclamation’s Grand Coulee Dam and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers’ Bonneville Dam were being built on the Columbia River. A new Federal bureau, the Bonneville Power Administration, was created to assume responsibility for marketing energy from the two dams, as well as future Federal dams in the Columbia River basin. Because the Pacific Northwest generated excess power and California needed more power to meet peak demands, it was decided to link the public and private systems so power could be shared when it was needed most in a particular place. The idea came to fruition in 1964, when Congress approved what was known as the “Pacific Northwest/Pacific Southwest Intertie,” which in time would integrate the nation’s largest Federal hydroelectric power system (the Bonneville Power Administration), the largest municipal system (the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power), and the largest group of private systems in the West (the California Power Pool, composed of the Pacific Gas and Electric Company, the Southern California Edison Company, and the San Diego Gas and Electric Company).

The intertie, which illustrated successful cooperation between public and private utilities despite their history of friction, also triggered cooperation between the United States and Canada to resolve power oscillation problems that arose when transferring high voltage over long distances. The device designed to remedy the problem became a required fixture on long transmission system generators throughout the world.

Along with the 1965 New York City Blackout, the 1973 oil embargo led to a new direction in U.S. energy policy. America’s domestic oil reserves already were low when Arab members of the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) cut off oil sales to the United States and other countries that supported Israel during the 1973 Arab-Israeli War. The embargo, which lasted from October 1973 to March 1974, posed a major threat to the U.S. economy and marked the end of the era of cheap gasoline.

In the wake of the oil crisis, Congress, in 1977, created the Department of Energy. Policies followed that separated the Federal hydroelectric power industry into two divisions: one to produce hydroelectric power; the other to market and transmit it. Today, Reclamation continues to oversee hydroelectric production at its 53 powerplants (as does the Corps of Engineers at its plants), but the Western Area Power Administration, created in 1977, oversees marketing and transmission in all of the American West except for the Pacific Northwest, still served by the Bonneville Power Administration.

Power and the Environment

The impact that growth and development had on the nation’s lands and its fish and wildlife was a matter of concern long before there was a U.S. Reclamation Service. As early as 1844, the New York Sportsmen’s Club drafted model laws to limit the hunting season for woodcock, quail, and deer, and the fishing season for trout. The nation’s first national park, Yellowstone, was established in 1872, and in the early twentieth century, during the administration of the conservation-minded Theodore Roosevelt, millions of acres were set aside as public parks, forests, and wildlife refuges – some made possible by Reclamation’s dams and reservoirs. In Idaho, for example, Roosevelt established the Minidoka National Wildlife Refuge in 1909. The refuge encompassed the area in and around Lake Walcott, created by construction of Minidoka Dam.

By 1910, every state had some sort of commission for the protection of wild game and fisheries. The concept of wildlife management, led by Aldo Leopold, began in the United States in the 1930s and included passage of the Fish and Wildlife Coordination Act. The Act was amended in 1946 to require those working under Federal permit or license to consider the impact on fish and wildlife when they undertook water projects.

The 1960s and 1970s brought deepened environmental awareness as Americans increasingly recognized that the water and electricity provided by Federal dams came at significant environmental cost, including lost habitat for fish and wildlife. Grand Coulee Dam, for instance, had forever blocked the natural round of migration of anadramous salmon into the upper Columbia River basin. A Reclamation reservoir also could destroy the landscape and archeological sites, as well as force the removal of entire communities.

As public consciousness and political support for environmental protection grew in the 1960s, Federal oversight intensified with legislation such as the Wilderness Act of 1964 and the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act of 1968, which sought to protect rivers in their natural state, including by excluding them from consideration for dam or hydroelectric power sites. The National Environmental Policy Act, signed into law in 1970, had a tremendous impact on Reclamation’s planning, design and operations because Reclamation, like other Federal agencies, was required to involve the public, assess the impact of its proposed actions on the environment, and seek to avoid or minimize damaging effects.

Since the 1980s, with most of the good spots to locate dams taken, the rate of dam construction in the United States has slowed considerably, and with it the number of new, large powerplants. But still, as the demand for power continues to grow, Reclamation has worked to improve the efficiency and increase the capacity of its existing hydroelectric powerplants through “uprating,” meaning the modernizing and rehabilitation of generators, and “rewinding,” which involves installing new copper-insulated wire in a generator. As of 2014, Reclamation had completed uprating and rewinding at 41 of the 53 powerplants it owns and operates, increasing generating capacity by approximately 20 percent.

The New Melones Powerplant on the Stanislaus River in California was the last of the big plants in Reclamation’s hydroelectric power program. The decade-long battle over construction of the New Melones Dam, which culminated with initial operation in 1979, was a signal that the end of the era of large dam construction had come. The controversy focused on the loss of a popular stretch of recreational white water, inundation of archeological sites, and flooding of the West`s deepest limestone canyon.

Looking to the Future

Harnessing water to produce hydroelectricity has evolved into a sophisticated and complex science since Reclamation’s early use of hydroelectric power on its Salt River and Minidoka projects. Today, Reclamation looks to weather satellites to predict rainfall and stream flows and uses computers to calculate the release of water from reservoirs, which now must take into account not only irrigation needs, but domestic and recreational needs, flood control, navigation, and fish and wildlife conservation.

Hydroelectric power has many advantages over non-renewable fossil fuels such as coal, oil, and natural gas. Water that produces electric current can be reused downstream for irrigation and other purposes once it has passed through the powerplant. Hydroelectricity also is more economical, costing, by one estimate, $69 per kilowatt to produce compared to $400 for oil-fired power. In addition, because hydroelectric plants start easily and can change power output rapidly, they are ideally suited for meeting times of peak demand, which is a significant and growing portion of hydroelectric use. At the same time, however, the production of hydroelectric power, depending on the scale of the project, requires high investment costs.

Worldwide, hydropower represents 19 percent of total electricity production. About 25 countries depend on hydropower for 90 percent of their electricity needs. In Norway, hydropower supplies virtually all (99.6 percent) of the country’s electricity. Fossil fuels and nuclear power produce most of the electricity used in the United States. Hydroelectric power accounts for only about 7 percent of the nation’s total power, with Bureau of Reclamation plants producing about 15 percent of the hydroelectric power. States such as Washington, Oregon, and Idaho rely upon hydroelectricity as their main power source, with much of that produced at Reclamation and Corps of Engineers powerplants. Washington State, the largest producer of hydropower in the nation, relied on hydro for about 75 percent of its power supply in 2007.

As the Bureau of Reclamation looks to the future as an important manager of water in the West, it is partnering with the private and non-federal sector to facilitate the development of power on Reclamation dams and canals that don’t currently generate power. Reclamation is also supporting the development of innovative hydropower technologies as it works to increase sustainable hydropower generation at sites not previously considered practical. For instance, Reclamation is testing a hydrokinetic unit on its Roza Canal near Yakima, Washington. Because the unit is hydrokinetic, it produces electricity in a free-flow environment with no need for a dam or canal drop. Hydrokinetic units, which usually generate electric power on small ponds, creeks, and waterfalls, are small in terms of electrical generation capacity, but they can generate enough electricity for an isolated family, small community, or rural industry.

In effect, as Reclamation and others interested in renewable energy strive for sustainability, the story of hydroelectric power is returning to its roots in the American West, where little dams on mountain streams powered plants like Ames, which operated on a small scale for a local purpose – to run the stamp mill at Colorado’s Gold King Mine.

Visit the National Park Service Travel Bureau of Reclamation's Historic Water Projects to learn more about dams and powerplants.

Last updated: January 18, 2017