Part of a series of articles titled Grand Canyon Centennial Stories.

Article

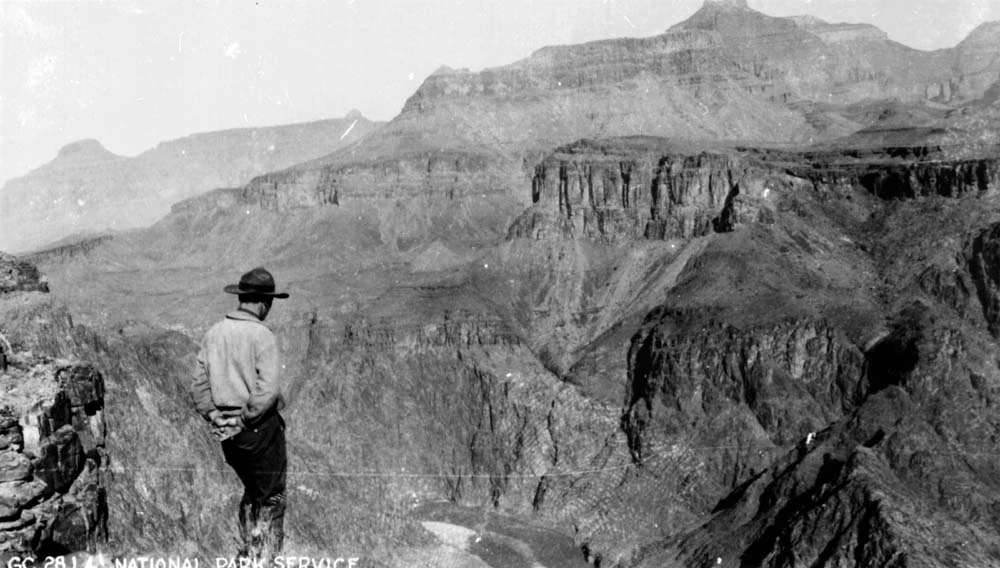

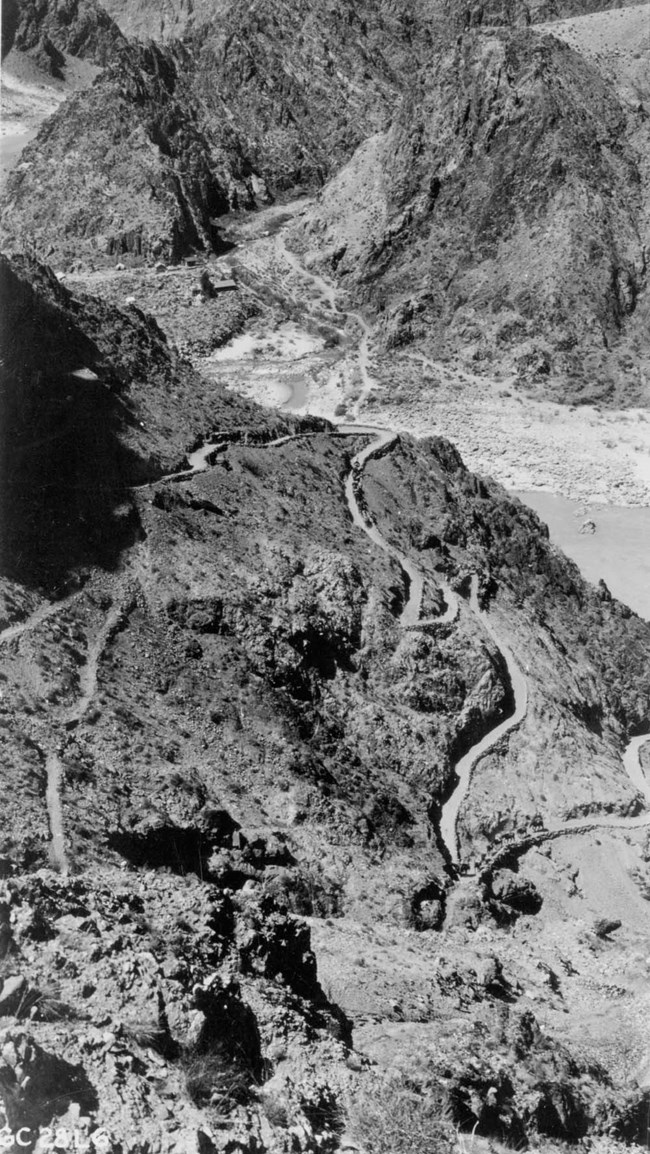

1925 - Building the Kaibab Trail

By Henry Karpinski

~

~

I would rather be on that dusty

windy

path than any place I know.

Open to the sky-

and at the mercy of

myself.

windy

path than any place I know.

Open to the sky-

and at the mercy of

myself.

The Chimney, Ooo-Ahh Point, Windy Ridge, the Red & Whites, the Tip-Off, the TrainWreck..… For those who know and love the Kaibab Trail, the recitation of these names conjures up images that are the stuff of longing, wonder, and enchantment.

The Kaibab Trail, for all its lore and its legions of devotees, is actually a “new” route down into the Grand Canyon, at least when compared with the Grandview, or Bright Angel, or even the Hermit. Built at a time when the National Park Service was struggling to overcome challenges to its then-recent assignation as the authority within the Park, the successful construction of the Yaki Trail (as it was briefly known) was crucial to establishing the National Park Service in a position of power at the Canyon. The relationship between the local population of Northern Arizona, especially around the GC area, and the Federal Government was never very good.A potent distrust existed for any authority that was perceived to limit private interests.When the Park was created, this distrust, resentment, even fear, came to the fore as stewardship of Grand Canyon fell to the National Park Service.Under the leadership of Stephen T. Mather the NPS began a campaign to eliminate private ownership of land within the borders of the new National Park.This confirmed the worst fears of the virulent anti-federalist.

For many years the Cameron (later Bright Angel) Trail was in private hands and those wanting to get down to the Colorado had to pay for the privilege (at least those utilizing any four-legged companions).In 1890 and ’91, along with his brother Niles and their associate, Pete Berry (and several others), Ralph Cameron re-worked an old Havasupai route into the Canyon, widened and improved it as far as Indian Gardens, and began operating the trail as a toll road.They extended it to the Colorado River about 1898.By 1906, after seemingly endless litigation involving Cameron, the Santa Fe Railroad and the United States Forest Service, the trail was under the control of Coconino County.Then came President Wilson’s signature on February 26th 1919 and the founding of Grand Canyon National Park.

One of the top priorities of the NPS was to gain ownership of the BA. Within two weeks negotiations with the county began in earnest with Interior Secretary Franklin K. Lane inquiring as to the Coconino County Board of Supervisors’ asking price.

The county’ initial reply of $150.000, angered the impatient Acting Superintendent W. H. Peters. He quickly had an alternate route to the Colorado surveyed and was ready to proceed with construction before the end of 1919, convinced that he could complete a new trail for $30,000. The old Fred Harvey Company saw that any effort to wrest control of the Cameron Trail from Coconino County was going to be a long process indeed, so within weeks of the NPS’s arrival on the scene, Harvey officials began pressing for an alternate route to the river.

Late in 1919, George E. Goodwin, the general engineer for the Park Service was called in to resume negotiations with Coconino County, the hope being that his agreeable, gentle manner would win over the Board.Goodwin offered new terms for the BA; that of either an outright payment of $77,118, or a $100,000 promissory note, the payment of which was dependent on the county using the funds to improve the access road from Maine (a town roughly halfway between Flagstaff and Williams).He also mentioned, gently, that the NPS stood ready to build a new trail just a few miles east of the Bright Angel should no agreement be reached.Negotiations continued for years.

By 1922, Congressman Carl Hayden of Arizona entered the picture.

“The idea occurs to me that Coconino County might make a profitable

trade in selling the trail.Tourist traffic is doubling almost every year and

the greater the attraction the Grand Canyon can be made as one of the

seven wonders of the world, the greater an asset it would be to Coconino

county, as well as all Arizona”.

trade in selling the trail.Tourist traffic is doubling almost every year and

the greater the attraction the Grand Canyon can be made as one of the

seven wonders of the world, the greater an asset it would be to Coconino

county, as well as all Arizona”.

Hayden reasoned that an improved road would boost visitation and that, in turn, would necessitate more federal money for the Park and, by extension, the county and state.Given that Coconino County was only making about $5,000 a year in revenues from the BA, the congressman viewed the government’s offer as very lucrative. He arranged for a meeting at the El Tovar in April of 1923 with Congressman Louis Crampton of Michigan, chairman of the Interior Department appropriations subcommittee, and Congressman Charles D. Carter of Oklahoma, a member of the same sub-committee.Also attending was the Coconino County Board of Supervisors and representatives from the National Park Service.Approval of the deal was secured at this gathering but not before the NPS offered an additional (and remarkable) incentive for the county. After the $100,000 was used on the Maine/Grand Canyon road as per the agreement, the Park Service would thereafter maintain the route, a proposition that would save the county millions in ensuing years!Convinced that the NPS was sincere in its desire to build a mutually agreeable working relationship with local interests, the Board of Supervisors accepted the agreement.

The plan precluded any need to proceed with the construction of another trail.

Had it stuck, the Kaibab might never have been built.

Had it stuck…

Consider the ongoing debate between the local newspapers into the mix and it’s understandable why the Coconino Board decided to take a different track.Though lending tacit approval for the deal reached at the El Tovar, the county had never officially finalized their decision.Now, in mid-September of 1924, with passions running high on both sides, the Board decided to sell the BA Trail at public auction.Since the Department of the Interior would be the only declared buyer it seemed that the dispute over the trail was finally near an end.

Enter Frank M. Gold, an attorney in Flagstaff, who,working with some citizens of Williams, filed a successful petition to place the question of the trail’s sale on the November ballot. There is little question as to the unseen hand of Ralph Cameron influencing this latest turn of events.Debra L. Sutphen, in her thesis, Grandview, Hermit, and South Kaibab Trails: linking the past, present and future at the Grand Canyon of the Colorado, 1890-1990 describes the atmosphere:

"Once more, the Coconino Sun and the Williams News assumed fighting stances, fervently deriding each other and their respective followers over this volatile issue. Additionally, an extensive propaganda campaign was waged by both sides, consuming dozens of pages of newsprint in equally strident efforts to persuade the voters of Coconino County of the merits of their respective arguments.Again, the reputations of several individuals were publicly called into question, among them attorney Frank Gold. As the election deadline approached, tempers flared and the conflict assumed a feverish urgency. All other election matters paled in comparison to the exposure afforded this highly charged issue…By November 4, tension between the two factions had reached an almost maniacal pitch."

The proposition failed.

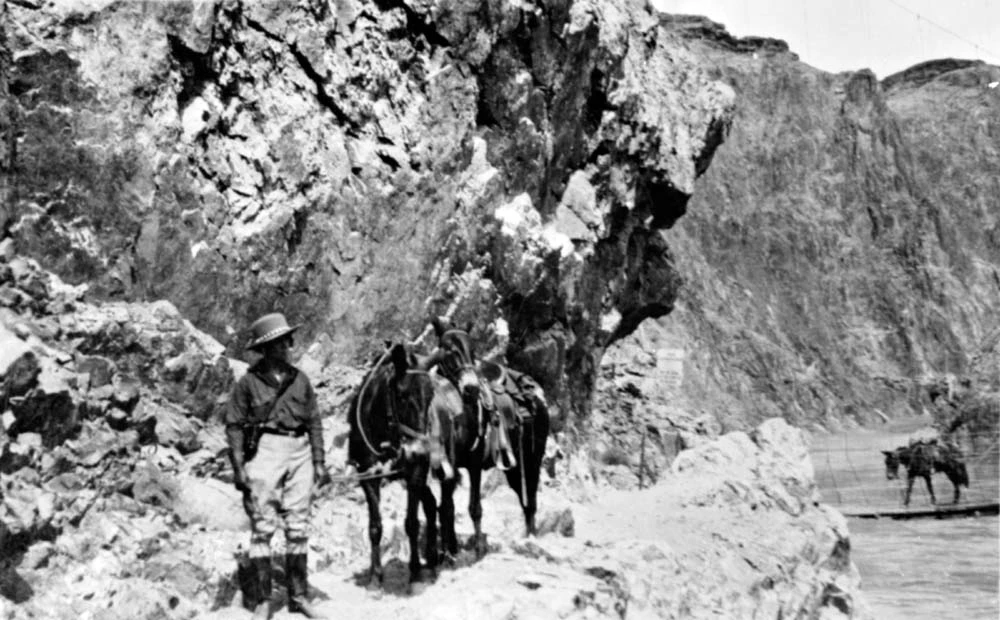

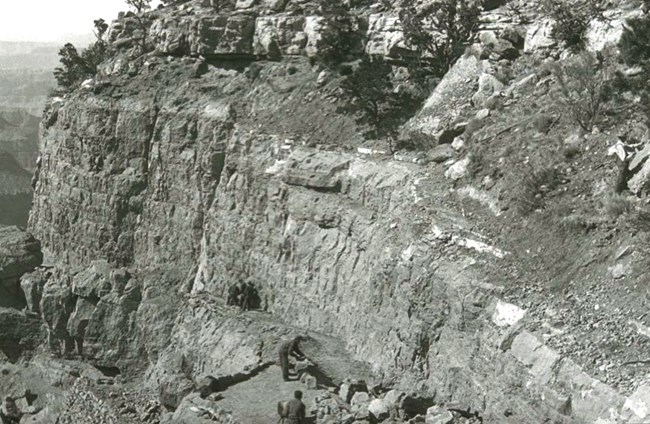

Embarrassed, and more than a little aware of their perceived weakness in Northern Arizona, the NPS decided that it was time for decisive action on their part.The immediate plans of the agency, and the success of the same, would color for years, even decades, their relationship to the local population and the various business interests in the area.It was quickly announced that work would begin on the Yaki Trail on December 1st, 1924.

"Very unfavorable conditions retarded progress on the Yaki Point Trail for the month of January.The lower limestone strata…is giving us much more trouble than anticipated.As an index of hardness, at one place it required 17 freshly sharpened bits to drill a hole eight inches in depth.The compressor used by the lower crew was idle three days due to waiting for spare parts."

Debra Sutphen:

"In a tense battle of will and determination the National Park Service had

achieved predominance within Grand Canyon National Park.This success,

represented by a precipitous, four-foot wide path, marked a significant

tipping of the scales of control at Grand Canyon—no longer would private

interests hold sway over the destiny of the mighty chasm."

achieved predominance within Grand Canyon National Park.This success,

represented by a precipitous, four-foot wide path, marked a significant

tipping of the scales of control at Grand Canyon—no longer would private

interests hold sway over the destiny of the mighty chasm."

There remained still another controversy, albeit not of the magnitude that sparked the years of newspaper war and character assassination.It concerned an official name for the trail.Yaki Trail was assumed to be the choice since most everyone had been using that term all through the months of construction. In fact, for years after “Kaibab Trail” was decided upon, many continued to call it the Yaki or Yaki Point Trail.But this name was never actually officially assigned to the structure.Fred Harvey, backed by Santa Fe, believing (mistakenly) that they still had some influence in the matter vis-à-vis the not inconsiderable resources they had just spent building Phantom Ranch, badly wanted “Phantom Trail”.Given that the trail led directly there, this was probably a more appropriate name, however the NPS, not in any mood to accede to any of the Harvey Company wishes, dismissed it outright.Stephen Mather himself wrote Superintendent Eakin:

"Harvey wants to use ‘Phantom’ because it leads to Phantom Ranch, on

which they’ve just spent lots of money.I think Kaibab is better, however, so

lets do that."

which they’ve just spent lots of money.I think Kaibab is better, however, so

lets do that."

Last updated: June 15, 2025