Last updated: November 29, 2024

Article

Written in the Water: Four Parks Wrap Up Phase I of New Genetic Census

Have you ever paused on a hike to filter fresh water by the side of a lake or flowing stream?

Over the past two years, field crews at Olympic National Park, Mount Rainier National Park, Lewis and Clark National Historical Park, and North Cascades National Park Service Complex have hiked many miles to do just that, carefully pumping liters of water through an ultrafine filter and dumping it out on the ground.

Wait, what?

NPS Photo/Popek

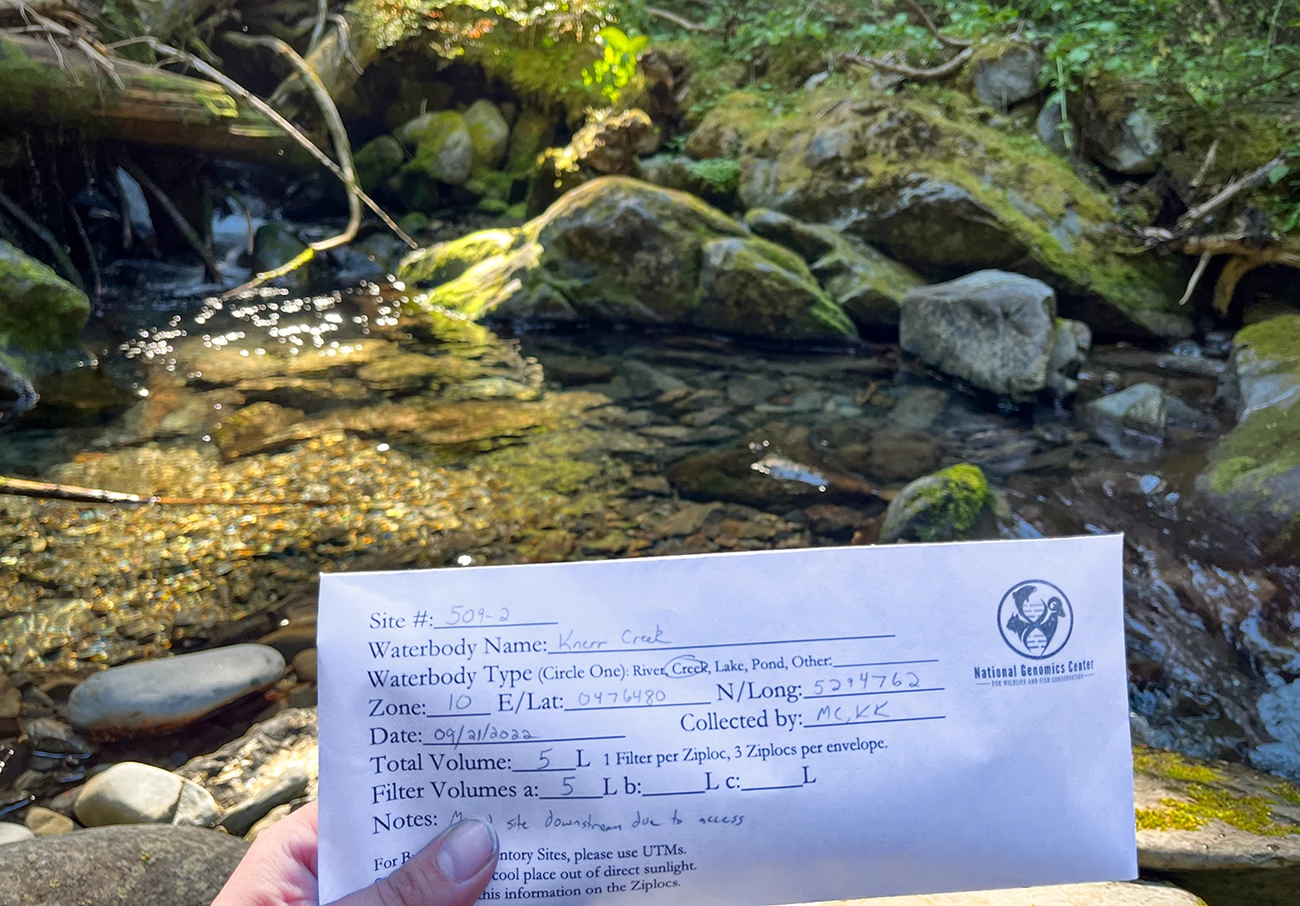

For biological science technicians collecting samples from hundreds of lakes, ponds, wetlands, streams, and rivers across four parks, the grand prize is…the dirty filter. Wearing sterile gloves, they use tweezers and a tongue depressor to carefully fold this precious circle of wet paper and tuck it safely into a baggie of silica. Caught by the microscopic pores of the filter paper are fragments of genetic code, revealing the identities of the water’s inhabitants.

Parts per Billion

DNA in water is one form of what’s known as environmental DNA, or eDNA. (eDNA can also be collected from seafloor sediments, animal tracks in the snow, flowers visited by pollinators, and even filtered from the air!) For species that are hard to observe or areas that are too big to survey, eDNA is a super-powered tool to answer a simple question: Who lives here?

DNA enters the water in a multitude of unappealing ways: through feces, mucous, gametes, sloughed-off skin cells, or even decomposing carcasses. It is these basic facts of life that have paved the way for a revolution in ecological monitoring in recent decades.

“In the past, a lot of the fish inventory in the interior lakes was conducted via raft and gillnet and big heavy things,” said Olympic fisheries biologist Sam Brenkman. eDNA sampling, by contrast, is easier on the knees of field crews that often backpack hundreds of miles in a single summer. “It’s an ultrasensitive, cost-effective technique that requires little equipment—and it’s detecting parts per billion of these organisms that are shedding DNA into the environment.”

Left to right: Cascades frogs (NPS photo), Anodonta sp. (used with permission), Northwestern salamander larva (NPS photo), salmon carcass (NPS photo)

Establishing a Baseline

Why are ecologists so concerned with who lives where in the first place? There are as many answers to that question as there are species. In Olympic, Mount Rainier, and North Cascades, a legacy of nonnative fish stocked in park waters by hikers, mule trains, and even aircraft has had long-lasting ecological consequences. Where native fish rub elbows with the interlopers, “you may have hybridization, species displacement, competition, and predation,” said Brenkman.

A different concern arises in lakes where fish were historically absent. With the arrival of new apex predators, native amphibians can be pushed out into nearby ponds and wetlands where they are more vulnerable to extremes of heat and drought. Through this study, managers will gain information to assess where salamanders and frogs may be in greatest jeopardy.

Other watery mysteries abound: What is the status of the chytrid fungus Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis (Bd), which has been responsible for large-scale amphibian declines in other areas? How can management actions like drawdown and refill prescriptions for Lake Chelan be planned to protect sensitive aquatic species? Which areas serve as critical refuges for threatened salmon? How should the headwaters of Lewis and Clark’s creeks be prioritized for land easement efforts?

Emerging from the many questions and answers is an ecological snapshot that can be referred back to in years to come. This inventory “establishes a baseline of what is where,” according to Mount Rainier biological science technician Nichole Ring. “In the future, this can show how species move in regard to climate change.”

Status Check

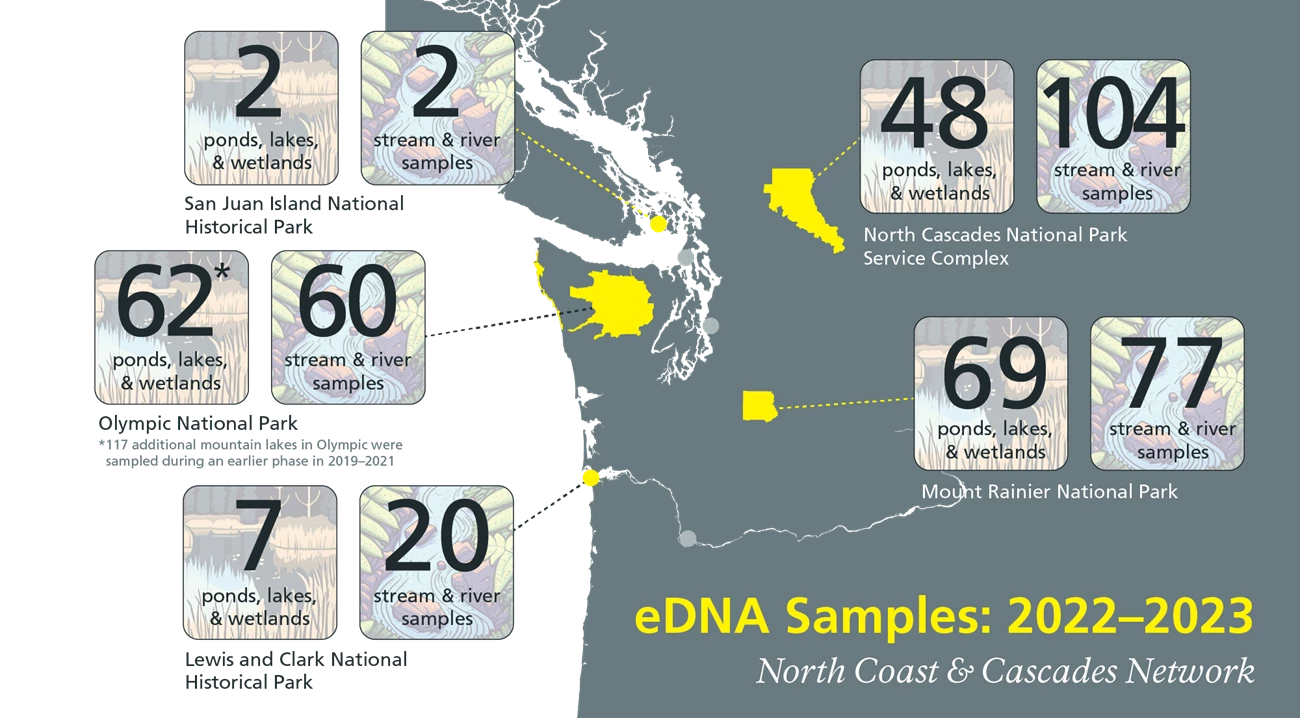

Over the past two years, teams have visited a grand total of 188 lakes, ponds, and wetlands, along with 263 river and stream sites across five parks. (In addition to the four primary study sites, a small number of samples were also collected at San Juan Island National Historical Park.)

eDNA Samples: 2022–2023

North Coast & Cascades Network

A map of the Pacific Northwest shows the locations of the eight North Coast and Cascades Network parks. Five parks where eDNA samples were collected are highlighted in yellow. Ponds, lakes, and wetlands sampled are counted separately from samples taken in streams or rivers.

San Juan Island National Historical Park

2 ponds, lakes, and wetlands sampled

2 stream and river samples

Olympic National Park

62 ponds, lakes, and wetlands sampled*

60 stream and river samples

*117 additional mountain lakes in Olympic were sampled during an earlier phase in 2019–2021

Lewis and Clark National Historical Park

7 ponds, lakes, and wetlands sampled

20 stream and river samples

North Cascades National Park Service Complex

48 ponds, lakes, and wetlands sampled

104 stream and river samples

Mount Rainier National Park

69 ponds, lakes, and wetlands sampled

77 stream and river samples

As the field portion of this project wraps up, hundreds of precious paper filters are being shipped to the USFS National Genomics Center for Wildlife and Fish Conservation in Missoula, MT. There, the isolated DNA will be analyzed and matched with a reference library of species, building a “who’s who” of the stream or lake of origin.

There’s just one problem: Scientists don’t yet have assays (specialized laboratory tests) that can detect the DNA of all 56 species that they hoped to inventory. As part of this research partnership, the National Genomics Center will need to develop five entirely new tests to detect eDNA from mountain whitefish, pygmy whitefish, Cope's giant salamander, speckled dace, and longnose dace. Once created, these assays can be used to detect these species in the future research, helping scientists everywhere better understand and protect aquatic communities.

NPS Photo/Kierczynski

Meanwhile, the NCCN scientists who came together to spearhead this project will await results from the National Genomics Center.

“We are continuing to learn about the park—it’s nonstop,” said Mount Rainier aquatic ecologist Rebecca Lofgren. “If we do get a hit somewhere that we didn’t know—a species—then it leads to more questions, and then we have the opportunity to go back and verify it and learn more. It’s another tool to keep us pushing.”