Last updated: December 24, 2021

Article

Wounded at Antietam, Civil War Soldier buried at St. Paul's suffered for 40 years, but wrote history of his famed regiment

unknown

Wounded at Antietam, Civil War Soldier buried at St. Paul’s suffered for 40 years, but wrote history of his famed regiment

Matthew J. Graham, who is buried in the historic cemetery at St. Paul’s Church National Historic Site, never really recovered from wounds received at the climax of the deadliest single day of the Civil War, stretching out a painful existence in New York for more than 40 years, but managing to write a classic history of his regiment, the 9th New York (Hawkins Zouaves) Volunteer Infantry.

An immigrant, like one fourth of the soldiers in the Union army, Graham was born in northern Ireland on November 21, 1836 to Presbyterian parents, and immigrated to America with his family in 1843, growing up in New York, the country’s largest city. Within weeks of the April 12, 1861 Confederate bombardment of Fort Sumter, amid the city’s fervent Unionist climate following President Lincoln’s call for volunteers to subdue the rebellion, the 24-year-old enlisted as a Sergeant in Company A, 9 th New York Volunteer Infantry, which was commanded by his older brother, Captain Andrew Graham.

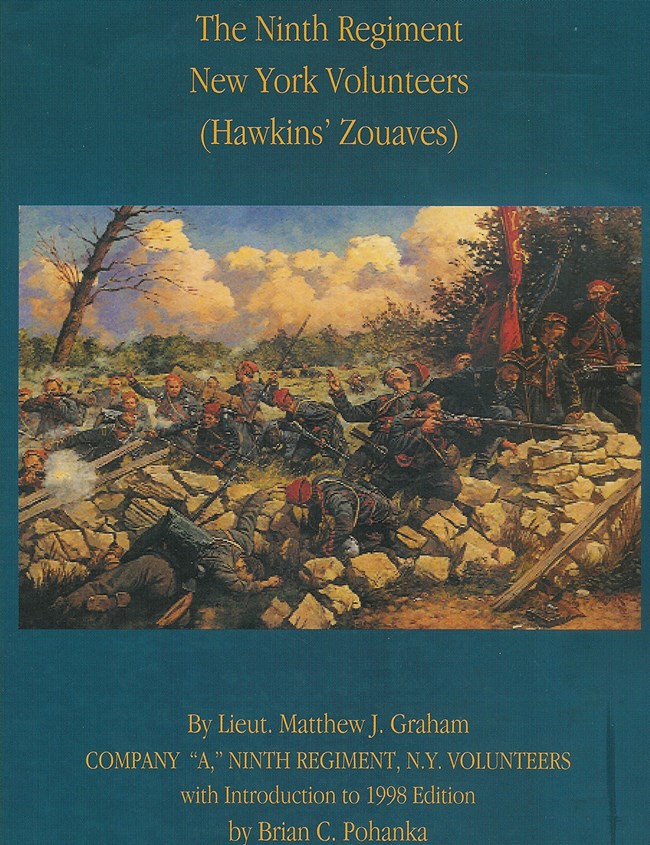

Matthew’s regiment was part of a peculiar fashion represented on the battlefields in the first year of the Civil War, the Zouaves. Emulating the appearance of Algerian units lauded for bravery, the Zouave uniform had emerged as a broad trend in military circles just as the American Civil War began. The most colorful element of the dress on the dark-haired, 5’ 9” Sergeant Graham, and most Zouave soldiers, were short (usually blue), open-fronted jackets, baggy red trousers, white sashes and fez turbans. At some level, these units believed that dressing in such distinctive apparel would instill in the soldiers the fierce, skilled fighting abilities of the legendary Zouaves from Algeria, who fought as colonial troops with the French army beginning in the 1830s. The distinctive garb made Matthew’s regiment recognizable and popular with New York newspapers and the public, and conspicuous on the battlefield.

Shortly after enlisting, Sergeant Graham returned to New York on a recruitment detail, and in addition to enrolling men in the Union army, married a woman named Maria Odell in a church service on August 22. Graham’s first experience with “the carnage and horrors of the battlefield,” as he later described it, occurred in an offensive against the Confederates on Roanoke Island, off the coast of North Carolina, in February 1862, and at South Mills in April, where the 9th fought with an expeditionary force under General Ambrose Burnside. Raised to the rank of Lieutenant on May 25, Matthew rose to greater command in Company A as a result of his brother’s illness and battle injuries, concurrent with the Confederate army’s first serious invasion of the North.

There is of course nothing inevitable about history, and looking backwards creates an illusory sense of inevitability, but Graham’s heroic moment astride a creek in Maryland almost carries that sense of destiny. This impression is supported by the dramatic narrative of his regimental history, written years later, and a letter he wrote to Colonel Hawkins in the 1890s recalling the episode of the Battle of Antietam. There was so much at stake at the clash of September 17, 1862 -- safety of Washington, D.C., possible British recognition of the Confederacy if the Southern armies were victorious, even Emancipation.

Late in the afternoon, at the south end of the battlefield, on the deadliest day of the war, Lieutenant Graham, in command because of his brother’s absence, led the company in one of the last and furthest advances over open ground, about a mile, against the Confederate lines of General A. P. Hill. The march was steady, with some breaks and, he recalled years later,

during one of these momentary halts I glanced back at the field we had just crossed and saw is sprinkled all over with our dead and wounded, all lying with their heads toward the enemy, presenting the appearance of a thin field of cornstalks I had seen some place, all rolled down to lie in the same direction for convenience in plowing them under. The charge ended so far as I was concerned, in what appeared to be a grand finale. We had been advancing over what I remember as rolling, but at the same time, rising ground; we had reached what looked like the summit of this particular ridge when we were met by what I remember as a crashing volley of musketry. We all went down together, although I was not hit with a bullet but with a grapeshot.

The brown eyed lieutenant’s right leg was broken, and he collapsed among dozens of dead and wounded men in blue. Carried to a field hospital behind the lines, the New Yorker’s smashed limb was amputated by Union surgeons four inches above the knee. His moment of military glory was very costly. After six months leave for injuries, with movement difficult on a shaky artificial limb, Lieutenant Graham was assigned to staff duties with the regiment’s Company F, although even that responsibility was hindered by pain and his limited mobility. Along with the rest of the 9th New York, he was mustered out of two year service in June 1863. His fighting tenure was over, but remaining in the service of the Union obviously meant a great deal to him, and Graham transferred to a wing of the Northern army called volunteer reserves, persevering with recruitment efforts for the next two years, before an honorable discharge in June 1865.

Continued medical complications with the right leg hounded Graham’s postwar life. Pension records list requests for funds to cover expenses for artificial limbs. Often in pain, he found it difficult to find work in the industrial cauldron of Gilded Age New York, but served as a clerk with the Customs House in lower Manhattan, positions often arranged for disabled veterans through local political connections. Living in Brooklyn, he and Maria never had children, and the marriage apparently fell apart, since there is no record of his wife after 1885. Like many veterans, memory of the war and pride in service sustained him. Graham was an officer in a Grand Army of the Republic veterans post and religiously attended reunions of the 9th Zouaves. Selection as the author of the regimental history reflected his martial contribution and literary ability. Produced in 1900, and written over several years by an aging veteran fraught with “intense agony,” it is a remarkable memoir of men, war, suffering, heroism, sacrifice and reconciliation. Reprinted in 1998, the tome runs more than 600 pages, and includes vivid accounts of a soldier’s life -- practical jokes, barely edible food, primitive living conditions, baseball as a camp pastime. Graham’s account of the unit’s 1889 trip to Savannah to visit a Georgia regiment is especially revealing of inter-sectional harmony achieved through Union/Confederate fraternization in the late 19th century.

Details on his final years are obscure, punctuated by a confrontation with a Government pension agent who visited the ailing Zouave’s Brooklyn home seeking clarification on his condition. Matthew was a pauper when he died at age 71, on October 23, 1907 at a New York hospital for the indigent. Burial followed four days later at St. Paul’s, and his grave is marked with a marble soldier’s stone. Graham lacked a religious or family connection to the Episcopal church in Mt. Vernon, but other veterans of the 9th are interred in the yard, including one wealthy parishioner, John Logan, who perhaps arranged a final resting place for his comrade.