Last updated: May 9, 2023

Article

World War I and the Philadelphia Navy Yard: Modernization of the US Navy (Teaching with Historic Places)

Introduction

The technology used by the U.S. Navy is always changing. One place that has been very evident is the Philadelphia Navy Yard (now the Philadelphia Navy Yard Annex) in Pennsylvania. The requirements of shipbuilding, repair, and docking changed the built environment of the navy yard and pushed the technology forward, especially as the U.S. transitioned from the nineteenth century into the twentieth. This was further advanced by the outbreak of World War I and the demands it placed on Naval power, worldwide.

The Philadelphia Navy Yard Annex provides an opportunity to learn not only about the technology of the U.S. Navy, but also about the lives of the people who lived and worked there. This includes Sailors, Marines, and workmen, who all experienced the world of the early twentieth century together in this place.

Lesson Contents

About this Lesson

Includes learning objectives, materials available for students, and details about visiting the site.

Connecting this Lesson to Curriculum

Situates this lesson within relevant U.S. history, social studies, common core, and social justice learning standards and Pennsylvania social studies standards.

Getting Started: Essential Question

Locating the Site

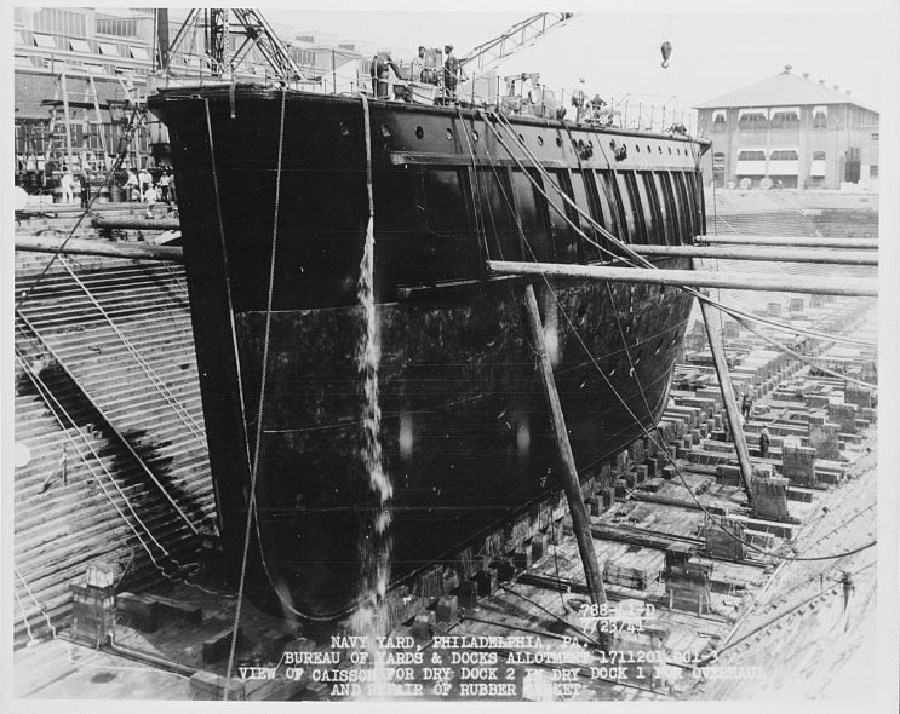

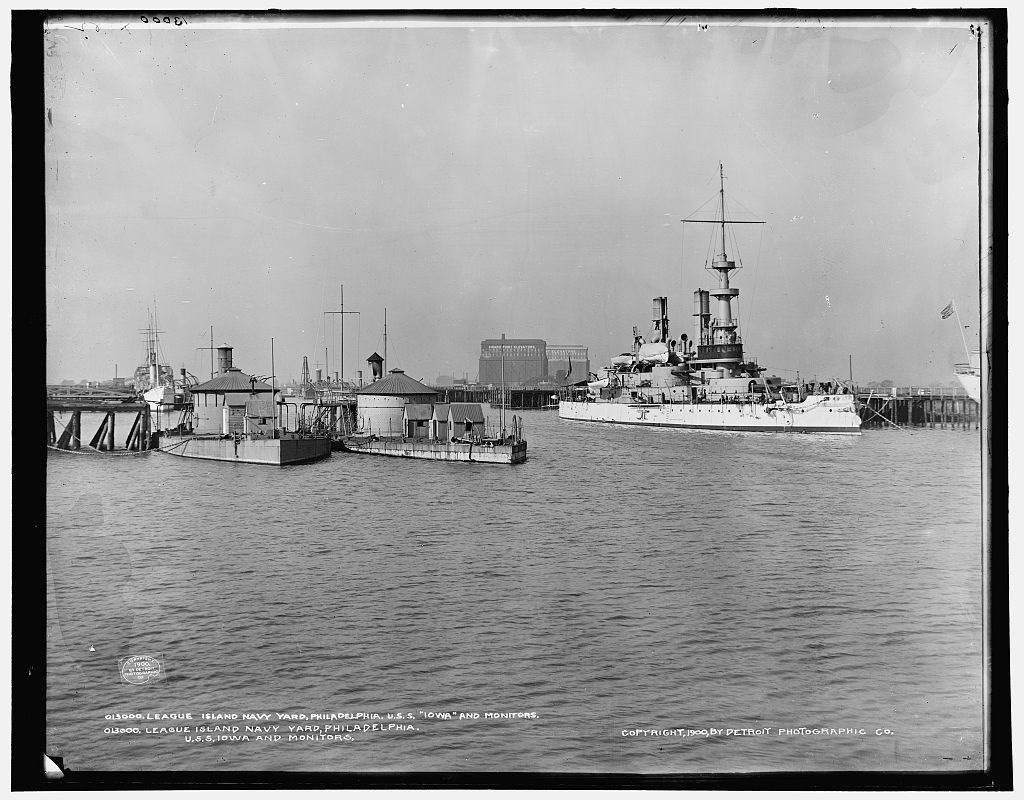

Map 1: A 1912 USGS topographic quadrangle map of Philadelphia and the surrounding area, highlighting the Philadelphia Navy Yard Annex at League Island

Readings:

Reading 1: Ironclads to Dreadnoughts: Advances in Shipbuilding Technology at the Philadelphia Navy Yard Annex (PNYA) (Page 10)

Reading 2: World War I and the United States Marine Corps (USMC) (Page 14)\

Optional Activities:

Activity 1: African American World War I Sailors, You be the Historian: Interpreting World War I Naval Enlistment Data

Activity 2: The Philadelphia Navy Yard Annex and the 1918 Influenza Pandemic through Archival Newspaper Accounts

References and Additional Resources

About this Lesson

This lesson plan, World War I and the Philadelphia Navy Yard: Modernization of the United States Navy, focuses on the Philadelphia Navy Yard at League Island. Today, the navy yard is known as the Philadelphia Navy Yard Annex, or the PNYA. This place is listed on the National Register of Historic Places (NRHP) as the Philadelphia Naval Shipyard Historic District (https://catalog.archives.gov/id/71997526). This lesson plan was developed on behalf of Commander, Navy Region Mid-Atlantic (CNRMA), in partnership with Naval Support Activity (NSA) Mechanicsburg, which currently oversees the PNYA. The lesson plan was created by Paul LaRue—a retired history teacher and education advocate, and Jessica Clark, the Cultural Resources Director for Ohio Valley Archaeology, Inc., with assistance from Sarah Lane, currently an elementary school teacher. Both Paul and Jessica are based in Ohio and Sarah works in Washington state. This lesson is one in a series that brings the power of place and historic sites to students around the world.

Objectives:

1.) Explore different maritime technologies and understand how the requirements of the Navy shaped the built environment at the Philadelphia Navy Yard Annex (PNYA);

2.) Illustrate the important role of the U.S. Navy in World War I (WWI), specifically U.S. Marines in France, who embarked from Philadelphia;

3.) Study enlistment trends among African American Sailors in the U.S. Navy in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries OR read newspaper articles from Philadelphia during the 1918 flu pandemic and compare and contrast those to life today.

Materials for Students:

1.) Map showing the Philadelphia Navy Yard Annex relative to the Delaware and Schuylkill Rivers and the city of Philadelphia.

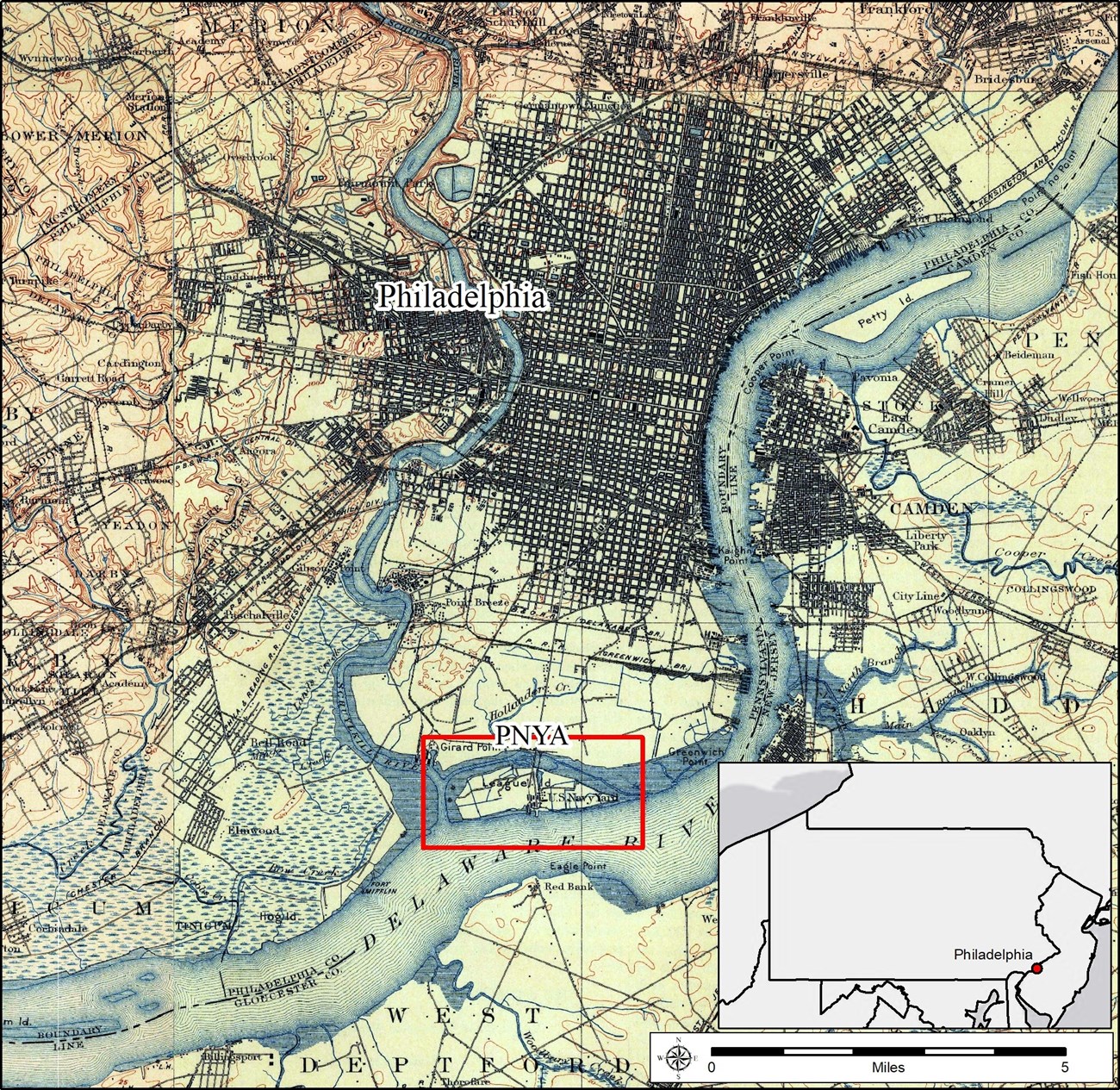

2.) Historic (c.1900) photograph of different ship technology docked at the PNYA.

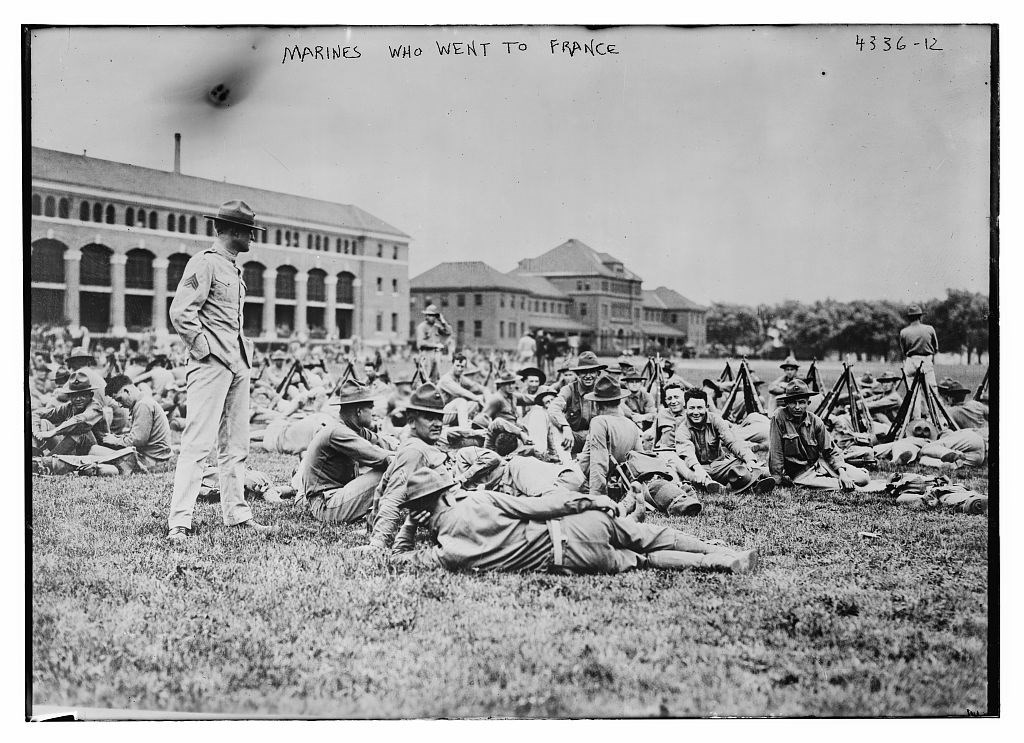

3.) Historic (1917) photograph of Marines on the Parade Ground at the PNYA, prior to embarking to France.

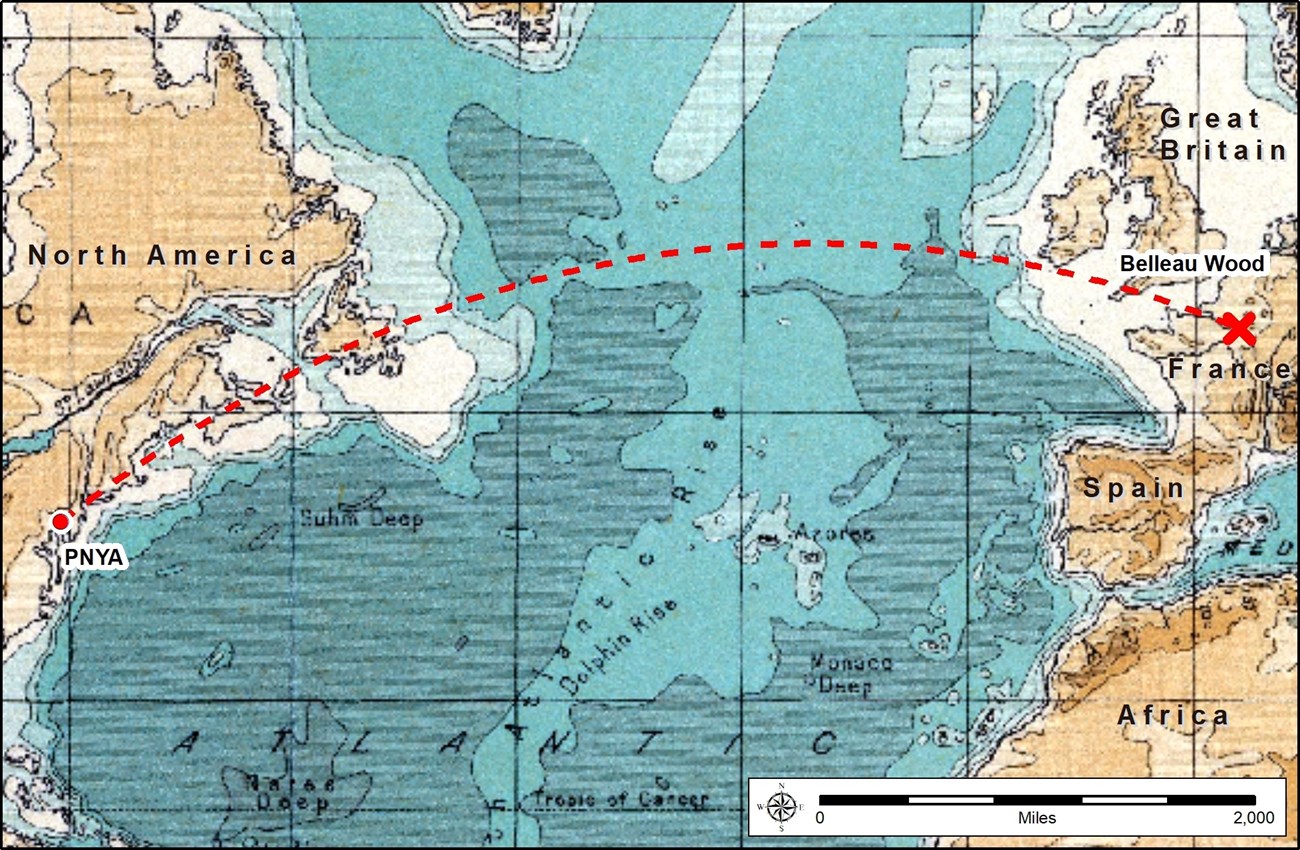

4.) Map showing the PNYA relative to Belleau Wood, France.

5.) Primary source newspaper clippings about the 1918 flu pandemic.

About the Philadelphia Navy Yard Annex:

The PNYA is located in southern Philadelphia, Pennsylvania where the Delaware and Schuylkill Rivers come together. Today, it serves a combination of military, private, and public sector purposes and many areas are open to the public. Additional details about things to see and do at the PNYA can be found at https://navyyard.org/.

Positioning this Lesson in the Curriculum:

- Time period: Early 20th century

- Topics: This lesson could be used in U.S. History, Geography, and World History courses and/or units on World War I. Students will analyze primary source documents aligned with informational texts to interpret and evaluate the impact of naval technologies as shown in the Philadelphia Navy Yard Annex. They will also examine and extend connections to diversity and discrimination in enlistments, and to pandemics and public health.

United States History Standards for Grades 5-12

This lesson relates to the following National Standards for History from the UCLA National Center for History in the Schools:

Era 7: The Emergence of Modern America (1890-1930)Standard 2: The changing role of the United States in world affairs through World War I

Curriculum Standards for Social Studies

This lesson relates to the following Curriculum Standards for Social Studies from the National Council for the Social Studies:

Theme I: Culture

- Standard B: The student explains how information and experiences may be interpreted by people from diverse cultural perspectives and frames of reference.

Theme II: Time, Continuity and Change

- Standard E: The student develops critical sensitivities such as empathy and skepticism regarding attitudes, values, and behaviors of people in different historical contexts.

Theme III: People, Places, and Environment

- Standard B: The student creates, interprets, uses, and distinguishes various representations of the earth, such as maps, globes, and photographs.

Theme IV: Individual Development and Identity

- Standard B: The student describes personal connections to places associated with community, nation, and world.

- Standard E: The student identifies and describes ways regional, ethnic, and national cultures influence individuals’ daily lives.

- Standard G: The student identifies and interprets examples of stereotyping, conformity, and altruism.

Theme V: Individuals, Groups, and Institutions

- Standard A: The student demonstrates an understanding of concepts such as role, status, and social groups.

Theme VIII: Science, Technology, and Society

- Standard A: The student examines and describes the influence of culture on scientific and technological choices and advancement, such as in transportation, medicine, and warfare.

- Standard B: The student shows through specific examples how science and technology have changed people's perceptions of the social and natural world, such as in their relationships to the land, animal life, family life, and economic needs, wants and security.

Theme IX: Global Connections

- Standard B: The student analyzes examples of conflict, cooperation, and interdependence among groups, societies, and actions.

- Standard D: The student explores the causes, consequences, and possible solutions to persistent, contemporary, and emerging global issues, such as health, security, resource allocation, economic development, and environmental quality.

- Standard E: The student describes and explains the relationships and tensions between national sovereignty and global interests in such matters as territory, natural resources, trade, use of technology, and welfare of people.

Relevant Common Core Standards

This lesson relates to the following Common Core English and Language Arts Standards for History and Social Studies for middle and high school students:

Key Ideas and Details

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RH.6-12.1

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RH.6-12.2

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RH.6-12.3

Craft and Structure

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RH.6-12.4

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RH.6-12.5

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RH.6-12.6

Integration of Knowledge and Ideas

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RH.6-12.7

Range of Reading and Level of Text Complexity

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RH.6-12.10

Pennsylvania Academic Social Studies Standards

This lesson relates to the following Pennsylvania Academic Social Studies Standards for alignment with teaching with state-based historical places, from middle to high school:

Civics and Government

Standard 5.4. How International Relationships Function

Geography

Standard 7.1. Basic Geographic Literacy

Standard 7.2. Physical Characteristics of Places and Regions

Standard 7.3. Human Characteristics of Places and Regions

Standard 7.4. Interactions between People and the Environment

History

Standard 8.1. Historical Analysis and Skills Development

Standard 8.2. Pennsylvania History

Standard 8.3. United States History

Standard 8.4. World History

Getting Started: Essential Question

How did industrialization and imperialism impact the U.S. Navy during, and immediately following, World War I?

What historical place might you study to answer this question and why?

Locating the Site

Map 1: A 1912 USGS topographic quadrangle map of Philadelphia and the surrounding area, highlighting the Philadelphia Navy Yard Annex at League Island.

Questions for Map 1

1.) This map of Philadelphia is from 1912. Do you think the city has grown since then? Explain why or why not.

2.) The Philadelphia Navy Yard (now the PNYA) was established as a place to build and dock large naval ships. As you can see from Map 1, the navy yard is not on the ocean where you might think a naval yard would be. Why do you think the U.S. Government might have chosen a location so far from the coastline for this navy yard?

3.) Do you think Philadelphia as a city is more or less important as a hub for the U.S. Navy than it was in the early twentieth century?

Reading 1

Ironclads to Dreadnoughts: Advances in Shipbuilding Technology and the PNYA

The Philadelphia Navy Yard at League Island, today known as the Philadelphia Navy Yard Annex (abbreviated the PNYA), was not always a hub for U.S. ship building.

During the Civil War, the U.S. Navy designed a type of ship known as an ironclad. This was a wooden ship clad—or covered—in thinly rolled sheets of iron. The iron was intended to protect the ships from the changing, modern explosive ordnance being used by the Confederate military. Previously, ordnance like cannon balls caused damage simply by force. By time of the Civil War, militaries were using ordnance that exploded on impact.

The U.S. Navy constructed the USS New Ironsides, an ironclad-type ship, at the Philadelphia Navy Yard Annex as a part of the effort to update and protect their fleet. This ship was 232 feet long and was covered in 2,000 square feet of 4 ½ inch armor plates. New Ironsides was officially christened on May 10th, 1862.

This style of ship, however, did not stand the test of time. In the late nineteenth century, there was a fundamental change in the way the U.S. Navy built ships. The vessels were different, and thus they required a different setting for construction. The Philadelphia Navy Yard Annex at League Island was being developed in the late nineteenth century, and its lack of sufficient infrastructure to support these changes was notable. In the decades following the Civil War, wooden ships fell out of favor and usefulness behind more modern, metal ships.

“League Island assumed a secondary role in this late nineteenth-century naval rebirth along the Delaware River because the Navy Yard lacked the modern industrial plant, machine tools, foundry, shipbuilding ways, and dry docks necessary to serve the new steel navy….Without dry docks, the Navy Yard could not inspect hulls, propellers, or rudders of new vessels brought to League Island for commissioning.”

The twentieth century brought with it an increased demand for fully metal steamships. This demand was intensified by World War I, for which a style of ship known as a dreadnought came about.

A dreadnought is a fully iron battleship with a different battery of guns than its predecessors. This was the vessel prioritized by the U.S. Navy as World War I was changing the way naval warfare operated. The development of dreadnought-type vessels in the U.S. was inspired by the British Royal Navy, that began developing these ships first.

At the Philadelphia Navy Yard Annex, this advancement in technology included the expansion of the facilities to accommodate larger ships and more diverse forms. World War I was the impetus for rapidly increasing the naval strength of the United States. By 1919 the PNYA contained the “most modern industrial plant available….” In addition to ships, they were also manufacturing aircraft and propellers in Philadelphia. These activities contributed to much of the industrial landscape that remains at the PNYA today, such as Dry Dock No. 3 and the propeller factory. It was in this era that the world’s largest hammerhead crane (at the time) was erected along the docks at the navy yard in Philadelphia. This massive piece of equipment simplified the construction process for much larger ships. Philadelphia was also not alone in this national effort.

Simultaneously, the U.S. Navy expanded operations at yards in Brooklyn, New York, and Norfolk, Virginia as war efforts increased demand for more and better ship technologies.

Questions About Reading 1

1.) What are two types of ships that the U.S. Navy used in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries?

2.) What country developed the dreadnought type ship that inspired the U.S. to develop similar ships?

3.) Did the Philadelphia Navy Yard Annex become more or less important to the U.S. as a whole during and immediately following World War I?

Photo 1: Ships docked at the PNYA, c.1900.

Questions About Photo 1

1.) What differences do you notice between the two ships on the left of Photo 1 and the one on the right?

2.) Do you think the differences you identified in the previous question mean the newer ships were better suited for the type of combat they faced in World War I?

3.) How have ships continued to change? Do U.S. Navy ships look different than this today?

Reading 2

World War I and the United States Marine Corps (USMC)

The U.S. Marine Corps was established November 10, 1775. The Marines participated in more than two dozen military engagements between 1775 and 1917. In 1899 a Marine Corps Reservation was established on League Island (the Philadelphia Naval Yard). The Reservation included barracks, officers’ quarters, and numerous other support buildings. The Marine Parade Grounds at the Philadelphia Naval Yard hold an important place in Marine history as the embarkment point of the Fifth Regiment USMC for France in 1917. The Fifth Regiment was the first regiment of Marines to leave for France, as part of the first expedition of American troops.

When the U.S. entered World War I on April 6, 1917, the Marine Corps had a total strength of 13,725 men. On June 14, 1917 the Fifth Regiment USMC left from the Philadelphia Naval Yard as part of the first expedition to France. The Philadelphia Naval Yard was one of two recruit depots for the Marines at the beginning of the war; the other was in Norfolk, Virginia. A recruit depot was a place where Sailors were trained prior to being sent to the war. The Philadelphia Naval Yard also maintained a supply depot during this time that sent large quantities of materials to support the Marines: more than 31,000,000 pounds of supplies were sent to France and the West Indies from Philadelphia.

June 6, 1918 is a significant day in the history of the U.S. Marine Corps (USMC). On June 6, 1918 at the Battle of Belleau Wood in France, more Marines were killed and wounded in combat than in the previous 143 years of Marine Corps history. The U.S. Marine Corps emerged from World War I as one of the most battle-tested and elite fighting forces in the world.

When the Fifth Regiment USMC arrived in France, they immediately began to support the Allied war effort. In June of 1918, the Fifth Regiment found itself near Chateau-Thierry, at a place called Belleau Wood. The Fifth Regiment fought gallantly at Belleau Wood through the month of June. More than 1,000 Marines lost their lives in combat during the Battle of Belleau Wood. The Fifth Regiment would fight in eight campaigns and five major battles while in France. Marines in World War I would be recipients of more than 1,600 decorations for bravery. This includes: five Medals of Honor and more than 1,200 Croix de Guerre.

One of the Marines that shipped out with the Fifth Regiment from the Philadelphia Naval Yard on June 14, 1917 on the USS De Kalb was Gunnery Sergeant Ernest Janson. Gunnery Sergeant Janson was the recipient of the Navy's Medal of Honor. His Medal of Honor citation reads:

"For conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity above and beyond the call of duty in action with the enemy near Chateau-Thierry, France, 6 June1918. Immediately after the company to which Gunnery Sergeant Janson belonged, had reached its objective on Hill 142, several hostile counterattacks were launched against the line before the new position had been consolidated. Gunnery Sergeant Janson was attempting to organize a position on the north slope of the hill when he saw 12 of the enemy, armed with five light machine guns, crawling toward his group. Giving the alarm, he rushed the hostile detachment, bayonetted the two leaders, and forced the others to flee, abandoning their guns. His quick action, initiative and courage drove the enemy from a position from which they could have swept the hill with machine-gun fire and forced the withdrawal of our troops."

By the end of World War I, 3,284 Marines had made the ultimate sacrifice of their lives and more than 9,500 additional Marines had been wounded. American Expeditionary Forces Commander General John J. Pershing said of the Marines at Belleau Wood: " ...Sturdily held its ground against the enemy's best guard divisions...".

Today we associate places such as Parris Island, South Carolina and Quantico, Virginia with the Marine Corps; but the Philadelphia Navy Yard Annex at League Island holds an important place in the history of the U.S. Marine Corps.

Questions About Reading 2

1.) Where in France were the Marines from Philadelphia in June of 1918?

2.) What honors did Marines from Philadelphia receive while fighting at Belleau Wood in 1918?

a.) Medals of Honor

b.) Croix de Guerre

c.) Both a and b

3.) Which regiment of the U.S. Marine Corps left from the PNYA? Were they the first group of U.S. Marines to serve in France?

Photo 2: Marines at the PNYA, 1917.

Question About Photo 2

1.) While we can’t know for sure what the Marines in this photograph were feeling, what kinds of emotions do you see in this image? Do you think they were excited or scared about the prospect of a major overseas war?

Map 2: Movement of the Marines from the PNYA to Belleau Wood in France during WWI.

Question About Map 2:

1.) If available to you, use the internet to look up how long it would take to fly to France from where you live. How much longer do you think it took the Marines to get to France on a boat instead of an airplane?

Optional Activity 1

African American World War I Sailors, You be the Historian:Interpreting World War I Naval Enlistment Data

African Americans have served in the U.S. Navy since the earliest days of the Revolutionary War. The Civil War was no exception to this. Unlike the U.S. Army (or the Union Army), which listed soldiers by race; the Union Navy did not document Sailors this way. Unfortunately, this means that it is not possible with 100% accuracy to state the exact number of African American Sailors that served the Union during the Civil War. Because of this, one of the most intriguing questions for researchers about African American Civil War Sailors serving in the Union Navy has always been: What was the actual number of African American Sailors who served?

In 1902, the Superintendent of the Naval War Records Office estimated that one in four Union Sailors were African American. Based on 118,044 total enlistments, that would make the number of African American Sailors 29,511. More recent scholars have put that number closer to 17,000 African American Sailors, which is slightly more than 14%. This is lower than originally thought.

Fifty years after the conclusion of the Civil War, World War I was underway in Europe and the U.S. Navy was preparing to join the fight. The manpower needed for a wartime Navy, required a dramatic increase in enlistments. We now know that by the end of World War I, approximately 538,000 officers and enlisted Sailors had served in the U.S. Navy, including more than 10,000 African American Sailors. Unlike in the Army, African American Sailors in the U.S. Navy did not serve in segregated units. Instead, African American Sailors served on nearly every ship. Several African American World War I Sailors made the ultimate sacrifice.

Official naval records began to list the race and ethnicity of Sailors in the early 1900s. This record keeping has allowed us to document the number of African American World War I naval enlistments and to analyze enlistment data of all Sailors from 1909 to 1919.

Ask students to review the enlistment data presented in the table, below, and then to answer the associated questions. Note, and consider discussing with students, that words (specifically words for people groups) that appear in historical documents and data are sometimes inappropriate by today’s standards.

U.S. Naval Enlistment Data

| Year | 1909 | 1910 | 1911 | 1912 | 1913 | 1914 | 1915 | 1916 | 1917 | 1918 | 1919 |

| White | 40,675 | 4165 | 44280 | 44261 | 44739 | 49052 | 48908 | 50496 | 96571 | 425323 | 238037 |

| Negro* | 1,768 | 1535 | 1529 | 1438 | 1491 | 1431 | 1265 | 1262 | 1285 | 5328 | 5668 |

| Chinese | 327 | 314 | 305 | 258 | 266 | 248 | 235 | 228 | 195 | 211 | 209 |

| Japanese | 256 | 261 | 230 | 210 | 206 | 198 | 167 | 143 | 120 | 130 | 108 |

| Filipino | 901 | 969 | 1042 | 1125 | 1137 | 1464 | 1726 | 1823 | 2001 | 3724 | 6134 |

| Samoan | 79 | 81 | 81 | 83 | 87 | 87 | 78 | 84 | 87 | 94 | 73 |

| Indian (US)* | 7 | 6 | 7 | 4 | 0 | 18 | 15 | 20 | 36 | 40 | 56 |

| Hawaiian | 16 | 25 | 21 | 18 | 19 | 25 | 14 | 20 | 47 | 203 | 227 |

| Porto Rican [sic]~ | 48 | 44 | 47 | 46 | 46 | 46 | 43 | 41 | 39 | 148 | 225 |

| GuamGuam/Chamorro* | 51 | 76 | 70 | 72 | 77 | 98 | 110 | 117 | 158 | 197 | 96 |

| Costa Rican | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 44129 | 45076 | 47612 | 47515 | 48068 | 52667 | 52561 | 54234 | 100539 | 435398 | 250833 |

*The terms from this chart come from the original 20th century Navy data. Keep in mind when reviewing historical documents that sometimes words are used to describe people or groups of people that are not considered appropriate by today’s standards

.~ “sic” is a Latin term meaning “intentionally so written.” Historians use this next to directly quoted material (like the data in this table) when something is spelled incorrectly or has some other error. In this case, the data from the Secretary of the Navy from the early 1900s wrote “Porto Rican,” but we know that it should be Puerto Rican, indicating people from the U.S. territory of Puerto Rico (https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/sic).

Notes on enlistment data:

a.) Source: Annual Report of the Chief of the Bureau of Navigation to the Secretary of Navy for the years 1909 to 1919

b.) The data is for the fiscal year; for example, fiscal year 1918 would run from June 30, 1917 to June 30, 1918

Questions for Activity 1

1.) Identify three enlistment trends using the data from the table.

2.) What is the percentage of African American Sailors to total enlistments in each of the following years?

a.) 1909

b.) 1918

3.) What might explain the changes in African American enlistments in the data gathered here?

4.) What might explain the percentage change in African American enlistments from the earlier Civil War Navy to that of World War I?

Optional Activity 2

The Philadelphia Navy Yard Annex and the 1918 Influenza Pandemic through Archival Newspaper Accounts

World War I is remembered for its brutal fighting by the Marines, advancing into deadly machine gun fire, unrestricted submarine warfare, and floating mines in the North Sea; yet the Influenza Pandemic of 1918 was deadlier to U.S. Sailors and Marines. The article: Influenza of 1918 (Spanish Flu) and the US Navy, stated: "... In 1918, Navy and Marine patients totaling 121,225 were admitted at naval medical facilities with influenza. Of these patients, 4,158 died of the virus, and sick patients spent over one million sick days in these facilities worldwide...". The number of Sailors and Marines killed in action in World War I was 2,892. A significantly higher number of Sailors and Marines died of the virus versus the number killed in action.

The entire City of Philadelphia struggled during the influenza pandemic and had one of the highest daily mortality rates among U.S. cities (1,700 deaths in a single day). Influenza first arrived in Philadelphia at the Philadelphia Navy Yard complex (today the PNYA) on September 18, 1918. The close living and working conditions of the naval yard and barracks allowed influenza to quickly spread to more than 600 Sailors. By the spring of 1919, 12,191 citizens of Philadelphia had died from influenza. The United States overall lost an estimated 675,000 citizens during the Spanish Influenza Pandemic of 1918.

Newspapers preserved in archives from this period allow us to read and analyze the conditions in Philadelphia during the 1918 influenza pandemic.

Ask students to read the two newspaper accounts of the 1918 flu presented below. The full articles can also be found online at the links provided. Note, and consider discussing with students, that words (specifically words for people groups) that appear in historical documents and data are sometimes inappropriate by today’s standards.

Reading archival newspaper accounts:

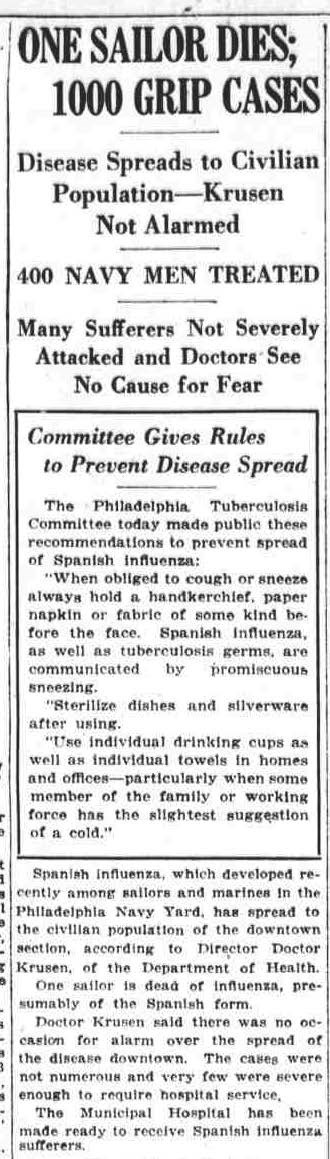

1.) September 19, 1918

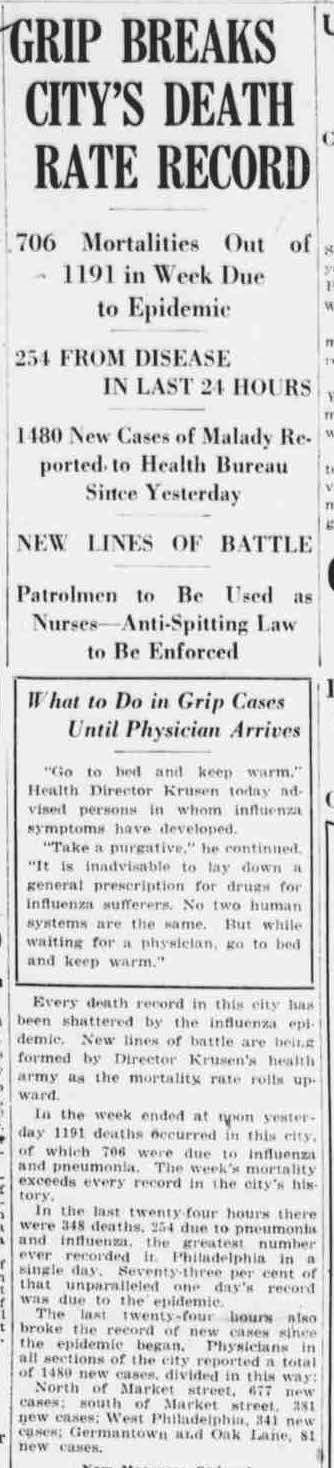

2.) October 5, 1918

TRANSCRIPTIONS

1.) September 19, 1918 (Transcription)

One Sailor Dies; 1000 Grip Cases

---------------------------------------------------

Disease Spreads to Civilian Population—Krusen Not Alarmed

---------------------------------------------------

400 Navy Men Treated

---------------------------------------------------

Many Sufferers Not Severely Attacked and Doctors See No Cause for Fear

Spanish influenza, which developed recently among sailors and marines in the Philadelphia Navy Yard, has spread to the civilian population of the downtown section, according to Director Doctor Krusen, of the Department of Health.

One Sailor is dead of influenza, presumably of the Spanish form.

Doctor Krusen said there was no occasion for alarm over the spread of the disease downtown. The cases were not numerous and very few were severe enough to require hospital service.

The Municipal Hospital has been made ready to receive Spanish influenza sufferers.

Dies in Naval Hospital

The victim was a sailor stationed at the Philadelphia Navy Yard. He died early today at the U.S. Naval Hospital, according to the announcement by the Chief Surgeon Pickerell.

The disease continued to spread among the sailors today, Doctor Pickerell said, and more sufferers were being treated at the hospital. He said nearly 400 sailors and marines were being treated at the Naval Hospital and at the League Island Hospital.

Doctor Pickerell said it had not been established whether the sailor, whose death occurred, was a victim of Spanish influenza. Death was due to influenza, he said, but whether or not it was the Spanish disease was not known.

He said every effort is being made to check the spread of the disease by isolation of those who have already fallen victims.

Many additional cases were reported today from the navy yard. Doctor Pickerell said he had no authority to speak of conditions at the navy yard. It is understood, however, that several hundred sailors and marines are in the hospital there, although information relative to the spread of the disease was withheld by authorities at the navy yard hospital. ...

2.) October 5, 1918 (Transcription)

Grip Breaks City's Death Rate Record

-------------------------------------------------------

706 Mortalities Out of 1191 in Week Due to Epidemic

--------------------------------------------------------

254 FROM Disease In The Last 24 Hours

--------------------------------------------------------

1480 New Cases of Malady Reported to Health Bureau Since Yesterday

---------------------------------------------------------

New Lines of Battle

----------------------------------------------------------

Patrolmen to Be Used as Nurses—Anti-Spitting Law to Be Enforced

Every death record in this city has been shattered by the influenza epidemic. New lines of battle are being formed by Director Krusen's health army as the mortality rate rolls upward.

In the week ended at noon yesterday 1191 deaths occurred in this city, of which 706 were due to influenza and pneumonia. The week's mortality exceeds every record in the city's history.

In the last twenty four hours there were 348 deaths, 254 due to pneumonia and influenza, the greatest number ever recorded in Philadelphia in a single day. Seventy-three per cent of that unparalleled one day's record was due to the epidemic.

The last twenty-four hours also broke the record of new cases since the epidemic began. Physicians in all sections of the city reported a total of 1480 new cases, divided in this way:

North of Market street, 677 new cases; south of Market street, 381 new cases; West Philadelphia 341 new cases; Germantown and Oak Lane, 81 new cases.

New Measures Ordered

In mapping out a campaign as a general plans a big drive, Director Krusen, other city officials and hospital and nursing authorities have ordered these new measures against the grip wave:

A rigid enforcement of anti-spitting ordinances, with fines for violators.

All swimming pools closed. Showers and tubs at these establishments permitted, however.

Superintendent of Police Mills will draft as emergency nurses every patrolman who has had any nursing experience.

Nurses of the city division of child hygiene have been withdrawn from child work and assigned to influenza cases.

The Women's Medical College has loaned its third-year and fourth-year students to hospitals. ...

Questions for Activity 2

1.) Find and read a local newspaper or online article about a recent pandemic. Create a list of similarities and differences between the 1918 articles and the modern one.

2.) How has your life been impacted by pandemics? How is your life different from those living in 1918? Write a short response.

Evening Public Ledger, Philadelphia, Thursday, September 19, 1918, page 2Link:https://panewsarchive.psu.edu/lccn/sn83045211/1918-09-19/ed-1/seq-2/#city=Philadelphia&rows=20&proxtext=Influenza&searchType=basic&sequence=0&index=12&words=influenza+Influenza&page=1

Evening Public Ledger and the Evening Telegraph, Philadelphia, Saturday October 5, 1918, Front pageLink:https://panewsarchive.psu.edu/lccn/sn83045211/1918-10-05/ed-1/seq-1/#city=Philadelphia&rows=20&proxtext=Influenza&searchType=basic&sequence=0&index=5&words=influenza+Influenza&page=1

References and Additional Resources:

Resources Available Online:

United States Navy Annual Reports https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/000067579

National Archives and Records Administration: African American Civil War Sailors https://www.archives.gov/publications/prologue/2001/fall/black-sailors-1.html

Naval History and Heritage Command: The Negro in the Navy https://www.history.navy.mil/research/library/online-reading-room/title-list-alphabetically/n/negro-navy-by-miller.html

Philadelphia, Nurses, and the Spanish Influenza Pandemic of 1918 https://www.history.navy.mil/content/history/nhhc/research/library/online-reading-room/title-list-alphabetically/i/influenza/philadelphia-nurses-and-the-spanish-influenza-pandemic-of-1918.html

Pennsylvania Newspaper Archive: Influenza 1918: https://panewsarchive.psu.edu/search/pages/results/?city=Philadelphia&rows=20&searchType=basic&proxtext=Influenza

Marine Corps University: Sergeant Major Ernest A. Janson, USMC (Deceased) https://www.usmcu.edu/Research/Marine-Corps-History-Division/Information-for-Units/Medal-of-Honor-Recipients-By-Unit/GySgt-Ernest-August-Janson/

Naval History and Heritage Command: NH 105318 Gunnery Sergeant Ernest A. Janson, USMC https://www.history.navy.mil/our-collections/photography/us-people/j/janson-ernest-a/nh-105318.html

Naval History and Heritage Command: Casualties: U.S. Navy and Marine Corps Personnel Killed and Wounded in Wars, Conflicts, Terrorist Acts, and Other Hostile Incidents https://www.history.navy.mil/research/library/online-reading-room/title-list-alphabetically/c/casualties1.html

Naval History and Heritage Command: Influenza of 1918 (Spanish Flu) and the US Navy https://www.history.navy.mil/research/library/online-reading-room/title-list-alphabetically/i/influenza/influenza-of-1918-spanish-flu-and-the-us-navy.html

National Register of Historic Places Nomination form: The Philadelphia Naval Shipyard Historic District. Douglas C. McVarish (John Milner Associates, Inc.). 1999. Accessed through the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) online.

Marine Corps Historical Reference Pamphlet: The United States Marine Corps in the World War. Major Edwin N. McClellan. Historical Branch, G-3 Division Headquarters, US Marine Corps, Washington, D.C. 1920 (facsimile reprinted in 1968). Accessed via https://www.marines.mil/Portals/1/Publications/The%20United%20States%20Marine%20Corps%20in%20the%20World%20War%20%20PCN%2019000411300.pdf“

Black Men in Navy Blue During the Civil War.” Joseph P. Reidy. Vol. 33, No. 3, Prologue Magazine, 2001. Accessed via the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) online.

“The Negro in the Union Navy.” Herbert Aptheker. Vol. 32, No. 2, The Journal of Negro History, pg. 169-200, 1947. Accessed via the JSTOR academic database.

“American Naval Participation in the Great War (with Special Reference to the European Theater of Operations).” Captain Dudley W. Knox. Hearings Before Committee on Naval Affairs of the House of Representatives on Sundry Legislation Affecting the Naval Establishment, 1927-1928, 70th U.S. Congress, 1st Session, House of Representatives, Committee on Naval Affairs, Naval History and Heritage Command, 1927-1928. Accessed via https://www.history.navy.mil/research/library/online-reading-room/title-list-alphabetically/a/american-naval-participation-in-the-great-war-with-special-reference-to-the-european-theater-of-operations.html

“Diversity, Inclusion, and Equal Opportunity in the Armed Services: Background and Issues for Congress.” Kristy N. Kamarck. Congressional Research Service Report, Naval History and Heritage Command. 2016. Accessed via https://www.history.navy.mil/research/library/online-reading-room/title-list-alphabetically/d/diversity-inclusion-equal-opportunity-armed-services.html

Books:

The Philadelphia Navy Yard: From the Birth of the U.S. Navy to the Nuclear Age. Jeffery M. Dorwart with Jean K. Wolf. University of Pennsylvania Press, Philadelphia. 2001.

United States Marine Corps in the First World War: Anthology, Selected Bibliography, and Annotated Order of Battle. Anette D. Amerman. History Division, United States Marine Corps, Quantico, Virginia. 2016. Accessed via https://www.usmcu.edu/Portals/218/WW%20I-Order%20of%20Battle.pdf?ver=2018-10-30-081422-220

The Fever of War: The Influenza Epidemic in the US Army During World War I. Carol R. Byerly. NYU Press, New York. 2005.

Ships for the Seven Seas: Philadelphia Shipbuilding in the Age of Industrial Capitalism. Thomas R. Heinrich. The Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore. 1997.

Images of America: Philadelphia Naval Shipyard. Joseph-James Ahern. Arcadia Publishing, Charleston, South Carolina. 1997.

Tags

- world war 1

- teaching with historic places

- military history

- military wartime history

- military

- ships

- shipbuilding

- wwi homefront

- wwi

- world war i

- delaware river

- philadelphia

- pennsylvania

- pennsylvania history

- twhp

- african american history

- african american soldiers

- gilded age

- progressive era

- spanish flu

- medical history

- epidemic

- u.s. in the world community

- migration

- immigration and migration

- migration and immigration

- science and technology

- national register of historic places

- twhplp

- etc aah