Last updated: June 17, 2022

Article

Jane and Sarah Work: Survivors of the Fort Vancouver School

NPS Photo

What we know about the lives of sisters Jane and Sarah Work is similar to what we know about other women from the time, place, and social class in which they lived. From the basic facts, we can gather about where they lived and when, and who their family members were, along with mentions of them written down by the men who knew them, we can piece together a loose understanding of their experiences. From this outline of facts we can imagine more about what their lives were like. There are hints at the warm and loving nature of their family. We can imagine the fear they felt when they fell ill while traveling far from home. Perhaps drawing from our own experiences, we can imagine the way they might have strived to please their parents by receiving an education, only to be disappointed and betrayed by the adults who were meant to care for them.

As you read about their lives, imagine yourself in their place, or their parents' place. What choices would you have made?

NPS Photo

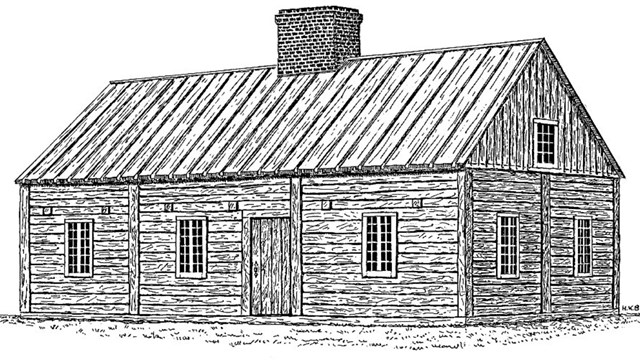

Early Life

Like many children of the fur trade, Jane and Sarah Work were Métis, with both European and Native American heritage. Their parents married in 1826 at Fort Spokane, a Hudson's Bay Company fort located at the confluence of the Spokane and Little Spokane Rivers. Their mother was Josette Legacé, the daughter of a Spokane woman and a French-Canadian fur trader. Their father was John Work, an Irishman who had joined the Hudson's Bay Company (HBC) in 1814. Josette was 15 years old at the time of their marriage. Just as the Works were married, Fort Spokane was closed. John was assigned with establishing a new HBC fur trade post at Fort Colvile, located along the Columbia River at Kettle Falls. At Fort Colvile, Jane was born in 1827. Sarah was born in 1829.

Like many Indigenous and Métis women married to fur traders, Josette traveled with her husband as he embarked on trading expeditions in the early 1830s, bringing their two little girls along. A third daughter, Letitia, was born in Idaho in 1831 during a fur trade expedition. As they traveled, Josette and other women with the group acted as interpreters, guides, and assistants in preparing furs.

These expeditions could be dangerous and grueling, especially for young children. From 1831 to 1832, the Work family embarked on their most dangerous expedition yet. In his journal, John Work described rampant illness, the death of another young girl in the group, desertions, severe weather, and several attacks by Blackfeet, one of which resulted in an injury to a Walla Walla housekeeper hired by the Works. As they traveled as far south as California, Josette and the girls contracted the fever that spread through the group. When they arrived at Fort Vancouver at the end of their journey, it must have been with a great sense of relief.

After watching his family endure this difficult experience, John Work found himself at a turning point in his career. In a letter he wrote in 1832 from Fort Vancouver, he told friend Edward Ermatinger:

The Work family lived at Fort Vancouver together until 1834, when John Work left for a new position as Chief Trader at Fort Simpson in present-day British Columbia. Josette stayed at Fort Vancouver until 1836, when she also moved to Fort Simpson. Jane (about age 9) and Sarah (about age 7) were left at Fort Vancouver to attend school."I am tired of the cursed country, Ned, and becoming more dissatisfied every day with the measures in it; things don't go fair, I don't think I shall remain long, my plan is to hide myself in some out of the way corner, and drag out the remainder of my days as quietly as possible. [Josette] is well, we have now got three little girls, they accompanied me these last two years, but I leave them behind this one, the misery is too great. I shall be very lonely without them, but the cursed trip exposes them to too much hardship."

NPS Photo

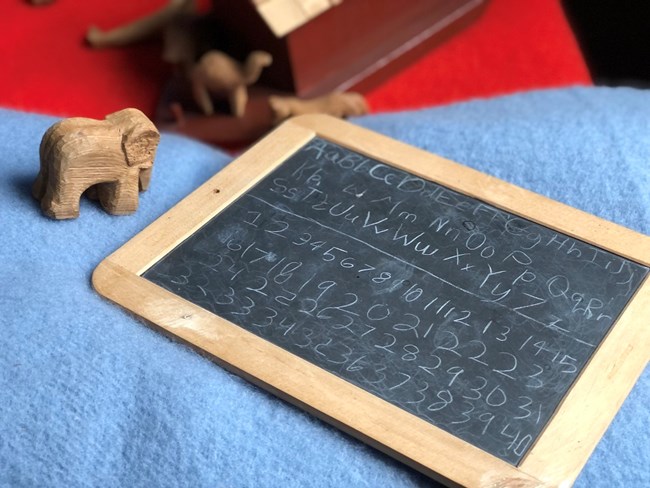

Attending School at Fort Vancouver

Hudson's Bay Company officers like John Work were under pressure from their employer to ensure that their Métis sons and daughters would be able to assimilate into mainstream Canadian society. Officers' children were expected to speak English rather than Indigenous languages and adhere to the Christian faith. These expectations concerned John Work as a father. He wrote to Edward Ermatinger that he hoped his children would learn "the fear of God." As John Work contemplated settling down, he probably wanted to see his daughters educated at the Fort Vancouver school to better help them acculturate to Canadian society, with the long-term goal of helping them find successful marriages and secure futures.

Until this point, the girls may have been receiving an informal education from their parents, including their mother, and hired help, like the aforementioned housekeeper. However, for fur traders who wanted their daughters to become "White gentlewomen," Native and Métis women were not seen as "proper" teachers. As early as 1807, Hudson's Bay Company officers issued a request for British women teachers for Métis girls at fur trade posts to remove the "need" for Native women "attendants," a word that presumably included the girls' mothers, aunts, grandmothers, and community. This early request was denied at the time because White women were still excluded from Hudson's Bay Company posts, but the interest in replacing Native and Métis women with White teachers persisted and grew. By the time the Work sisters arrived at Fort Vancouver, White women, usually missionaries' wives, were present at and around HBC posts. John Work could have been satisfied that his daughters would receive exposure to non-Native teachers at the fort school.

Over the next two years, Jane and Sarah Work attended the school managed by Church of England Reverend Herbert Beaver and HBC schoolmaster John Fisher Robinson. The sisters may also have been taught by Jane Beaver, Herbert's English wife, and received sporadic lessons from visiting American missionaries Eliza Spalding and Narcissa Whitman. However, the school and its curriculum were a source of controversy between the Beavers and Fort Vancouver's Chief Factor Dr. John McLoughlin. John Work wrote to friend Francis Ermatinger (Edward's brother): "there are ample means of getting my girls educated pretty well here [at Fort Vancouver] were it not for the damned bickering."

In 1838, Fort Vancouver Chief Trader James Douglas discovered that Robinson was sexually abusing female students. In October of that year, Robinson was prevented from leaving Fort Vancouver aboard the ship Columbia, brought back to Fort Vancouver, tried, found guilty, and flogged over the cannons that stood in front of the Chief Factor's House. He was dismissed from the Company and returned to England nearly a year later.

In a letter, Francis Ermatinger wrote:

It is unclear if Ermatinger's statement refers to Jane or Sarah, who would have been about 11 and 9 years old, respectively, in 1838. Ermatinger also wrote that Robinson's flogging wasn't punishment enough and that, in Ermatinger's opinion, Robinson should have been shot."The school master [Robinson], it would appear, has been in the habit of taking advantage of the female part of his pupils and our friend Work's daughter has had her share of the odium, altho' a mere child yet."

Following this incident, some parents unenrolled their children in the Fort Vancouver school and moved them to the American Methodist Mission school on the Willamette River. This was the case for Jane and Sarah Work, too.

In the aftermath of the Robinson scandal, the Fort Vancouver school was viewed as disorganized and immoral, and in need of serious reform. By 1841, visiting American naval officer Charles Wilkes noted that the Fort Vancouver school was segregated by sex, with boys and girls learning separately, attended by teachers of their own gender. The girl students lived with their female teacher. Robinson's crimes also brought about a heavier emphasis on morality in the school's curriculum. Wilkes wrote: "the officers of the Company...exerting themselves to check vice, and encourage morality and religion, in a very marked manner."

Schools for Indigenous and Métis children at Hudson's Bay Company posts were, in many ways, precursors to "Indian boarding schools" or "residential schools." Boarding and residential schools were key parts of an educational system set forth by the American and Canadian governments for Indigenous and Métis children in the 19th and 20th centuries. These schools aimed to "civilize" children by attempting to destroy their connections to their Indigenous families, communities, and cultures. Documented by inquiries like that of the Canadian Truth and Reconciliation Commission and the U.S. Department of the Interior's Federal Boarding School Initiative, sexual abuse of students was frequent at boarding schools. Tragically, the experiences of Jane and Sarah Work would not be isolated incidents, but early examples of a horrific pattern of abuse.

NPS Photo

Later Life

In 1841, Josette came to collect her children and moved them to Fort Simpson. Following this, John Work educated his daughters himself. According to historian Juliet Pollard: "He taught them how to garden, canoe, fish and skate, but would not allow them to dance." Letitia Work, Sarah and Jane's younger sister, later remembered:

In 1849, 22-year-old Jane Work married 37-year-old William Fraser Tolmie. Tolmie had worked for the Hudson's Bay Company as a surgeon and clerk since 1833. He had been stationed at Fort Vancouver before eventually becoming the Chief Trader, then Chief Factor of Fort Nisqually. Tolmie was likely quite aware of his wife's traumatic experience in the Fort Vancouver school, and the school's reputation at the time. In his journal kept during the 1830s, Tolmie lamented that children (including his future wife) had been exposed to "the vitiated [impure] moral atmosphere of Vancouver." Together Jane and William Fraser Tolmie had 14 children, not all of whom survived to adulthood. Jane died in 1880 at the age of 52."The Work girls had lessons every day except Sunday & Saturday with their father - on those days they sewed & repaired their clothing - each of the older girls had charge of the clothes of one of the younger children. Sunday morning after the house was put in order Mr. Work would gather his family to read the church services & a sermon, he also taught them the catechism - in the afternoon if it was fine he would take them for long walks outside [Fort Simpson] - In the evening they would again have prayers & not infrequently [younger sisters] Margaret & Mary who were small would fall asleep in a devotional attitude with their faces buried in the sofa cushions. Mr. Work would shake his head & say: Tut, Tut! My daughters... those were the only words of reproof he ever uttered in his family."

Also in 1849, 20-year-old Sarah Work married 31-year-old Roderick Finlayson. Finlayson had begun his career in the fur trade in 1839 as a clerk at Fort Vancouver and had served at HBC posts throughout the Northwest. When they married, he was the clerk in charge at Fort Victoria. Sarah and Roderick Finlayson had 11 children together. Sarah died in 1906 at the age of 76.

The education of the Work girls, both at school and at home, likely contributed to the achievement of what was undoubtedly one of their parents' chief goals for them: marriages to successful White fur trade gentlemen. However, during their engagement Tolmie still found his fiancée's education deficient. He "urged the Methodist missionaries Rev. Leslie Frost and his wife to accept his betrothed...and one of her sisters into their home." Tolmie wrote that he felt "confident that [Jane] would derive lasting benefit from a residence in your amiable family where she would see the worship of God performed in spirit and in truth and be taught both by precept and example." In pursuit of an education, Jane Work had been separated from her family, exposed to a predator, and forced to try her best to become a "White gentlewoman" in a world that would always regard her as a Métis fur trader's daughter.

Learn more about the school at the Hudson's Bay Company's Fort Vancouver.

Learn more about childhood at Fort Vancouver in this article series.

Bibliography

Brown, Jennifer S.H. Strangers in Blood: Fur Trade Company Families in Indian Country. Vancouver: UBC Press, 1980.

Halliday McDonald, Lois. Fur Trade Letters of Francis Ermatinger. Glendale: Arthur H. Clark Company, 1980.

Hussey, John A. The History of Fort Vancouver and Its Physical Structure. Portland, OR: Washington State Historical Society, 1957.

Jesset, Thomas E, Ed. Reports and Letters of Herbert Beaver. Portland, OR: Champoeg Press, 1959.

Lewis, William S. and Paul C. Phillips, Eds. The Journal of John Work, A chief-trader of the Hudson's Bay Co. during his expedition from Vancouver to the Flatheads and Blackfeet of the Pacific Northwest. Cleveland: Arthur H. Clark Company, 1923.

McIntyre Watson, Bruce. Lives Lived West of the Divide: A Biographical Dictionary of Fur Traders Working West of the Rockies, 1793-1858. Kelowna, BC: The Centre for Social, Spatial, and Economic Justice, the University of British Columbia, Okanagan, 2010.

Pollard, Juliet Thelma. The Making of the Métis in the Pacific Northwest, Fur Trade Children: Race, Class, and Gender. Ph.D. thesis, University of British Columbia, 1990.

Sampson, William R. "John Work." Dictionary of Canadian Biography. Accessed online here.

Van Kirk, Sylvia. "Josette Legacé." Dictionary of Canadian Biography. Accessed online here.