Last updated: September 11, 2025

Article

Women on Fort Alcatraz

California State Library.

An Essential Occupation

The laundresses, or washer-women, were some of the few women employed by the military to do laundry for companies of soldiers. They received rations, housing, medical care, as well as pay – in fact, laundresses on Alcatraz earned better pay than many soldiers! A laundress could make $40.00 per month, while the average soldier earned around $16.00 a month. Even officers’ wives, considered a higher social status, did not have the privileges that the laundresses did.

Library of Congress

Laundry for the military was hard but important work. Laundry was required to maintain the standards of order and cleanliness, but the laundresses of the 1800s had a lot on their plates. Army regulations during the Civil War (1861-1865) stated that there would be four laundresses for each company of one hundred men, meaning that each laundress was doing the laundry of at least 25 men. This took days. First women would sort the laundry, treat any stains, and complete any extra mending. Then they would soak the clothes (sometimes for several days), scrub them, ring them out, boil them, rinse them, ring them out again, and finally set it all to dry. For officers, the clothes might be blued, starched, and pressed.

The Laundresses on Alcatraz

On Alcatraz, many women supported the fort laundry operations. After all, where would we be without any clothes?

In the 1860 census, three laundresses appear:

- Ellen Taylor, age 21, born in Ireland

- Bridget McDonald, age 34, born in Ireland

- Mary Phelan, age 18, born in New York

In 1870, there were five laundresses:

- Ellen Moore, age 28, born in Ireland

- Mary Bombury, age 20, born in Ireland

- Bridget Madden, age 34, born in Ireland

- Rose Mitchell, age 35, born in Ireland

- Bridget Lynch, age 26, born in Ireland

Most of the women had children and probably helped each other with childcare. Clearly, Irish women immigrants, moving from the east to the west, were the backbone of Alcatraz domestic work.

National Archives

Bridget Madden is a particularly great example of many laundresses’ experiences. Most laundresses were married to enlisted men. Bridget’s husband was likely a man named John Madden, 36, from Ireland, and listed as a soldier in the 1870 census. In fact, the army regulations encouraged that the number of enlisted men’s wives who could join the company would equal the number of laundresses that the company needed. This was a way for women to accompany their enlisted husbands while also contributing to army operations and bringing in quite a bit of money for the family. Bridget almost certainly made more money than John.

“Four laundresses are allowed to each company, and soldiers’ wives may be, and generally are, mustered in that capacity. They are then entitled to the same quarters, fuel, and rations as a soldier, and the established pay for the washing they may do for soldiers and officers.”

- Kautz, General A. V. Customs of Service. Paragraph No. 11. 1864, in Tubs and Suds by Virginia Mescher

Staying together as a family was probably a priority for Bridget. In 1870, she had four kids living with her: Mary Jane (13), Michael (6), Fergus (4), and Thomas (2). The kids moved around as much as Bridget and John did. Mary Jane was born about 1857 in New York, possibly where John’s artillery company was stationed. Then, circa 1864, Michael was born in Virginia, probably while his parents were there towards the end of the Civil War. Fergus and Thomas were born around 1866 and 1868, respectively, in California, once the company moved to San Francisco after the war. Not only did Bridget and John immigrate all the way to America, but their whole family moved all over the country!

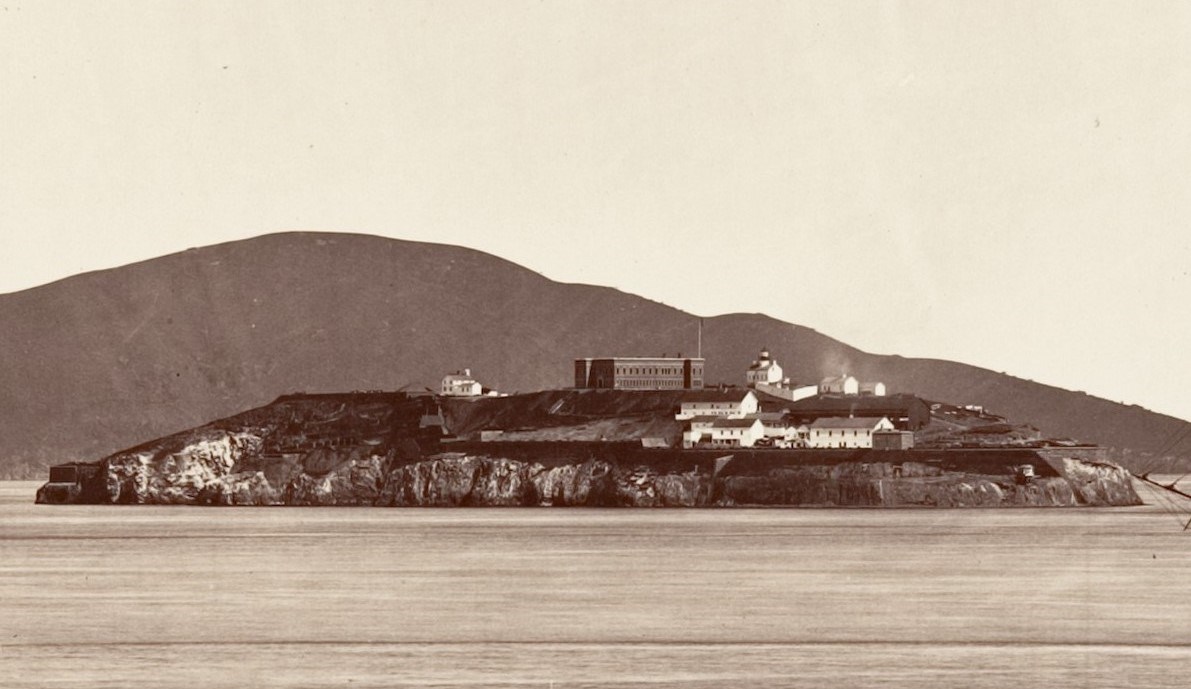

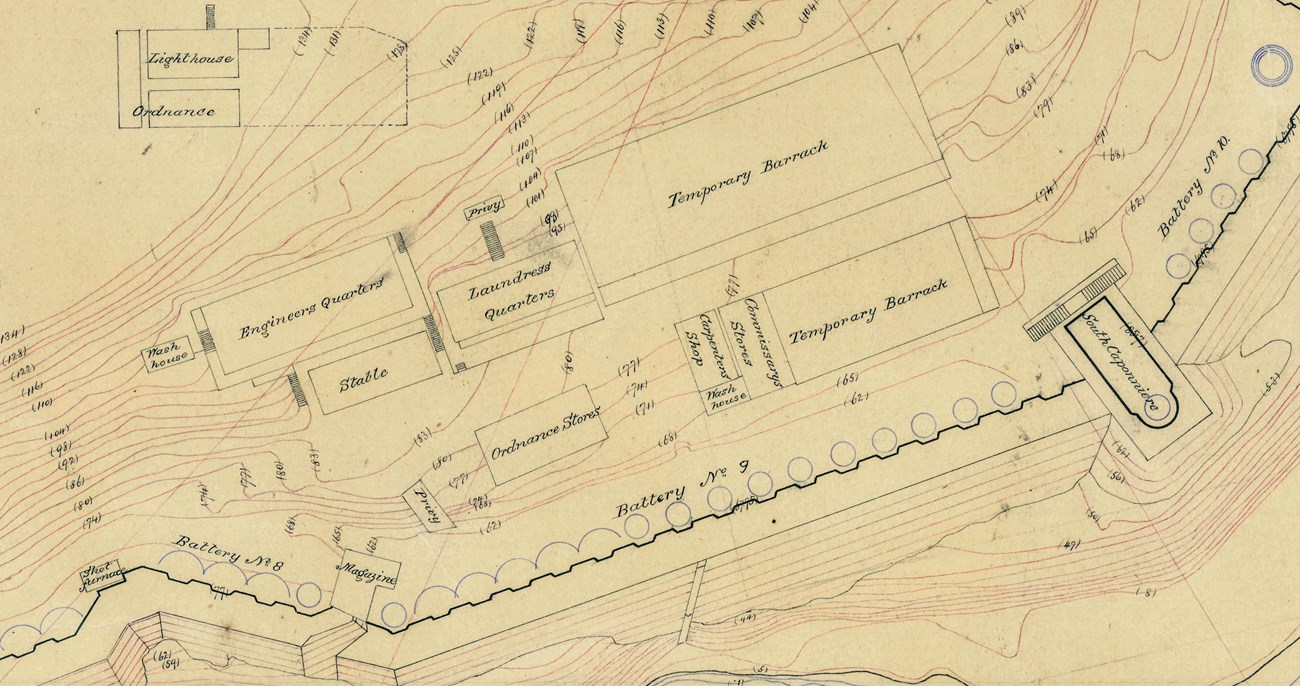

The island would have looked very different for these women than it does for visitors today. Defensive cannon fortifications and a three-story brick citadel dominated the island’s profile. While there were laundresses’ quarters in the plan for the citadel, by 1867 a map of the island indicated that the laundresses lived in a frame building on the southwestern slope of the island facing San Francisco. It is unclear whether their husbands lived with them or in the barracks. The wind around the laundress quarters was probably persistent, and the salt air might have stiffened the lines of drying laundry.

National Archives and Records Administration

Life After Laundresses

The archive has not recorded how long these women were on the island, but by 1883 the army stopped providing rations to laundresses, effectively ending their employment. In 1907 Alcatraz became a military prison and by November of 1911, soldiers who were incarcerated there were doing laundry in a concrete building on the north end of the island.

Frequently forgotten, the laundresses of Alcatraz made possible the many years that the island stood guarding the San Francisco Bay. And though laundry has an even longer history on the island than the laundresses, these women started it all.