Part of a series of articles titled Women of the Pimería Alta.

Article

Women of the Pimería Alta-Establishing Missions

Library of Congress

Women’s Roles in the Establishment of the Missions

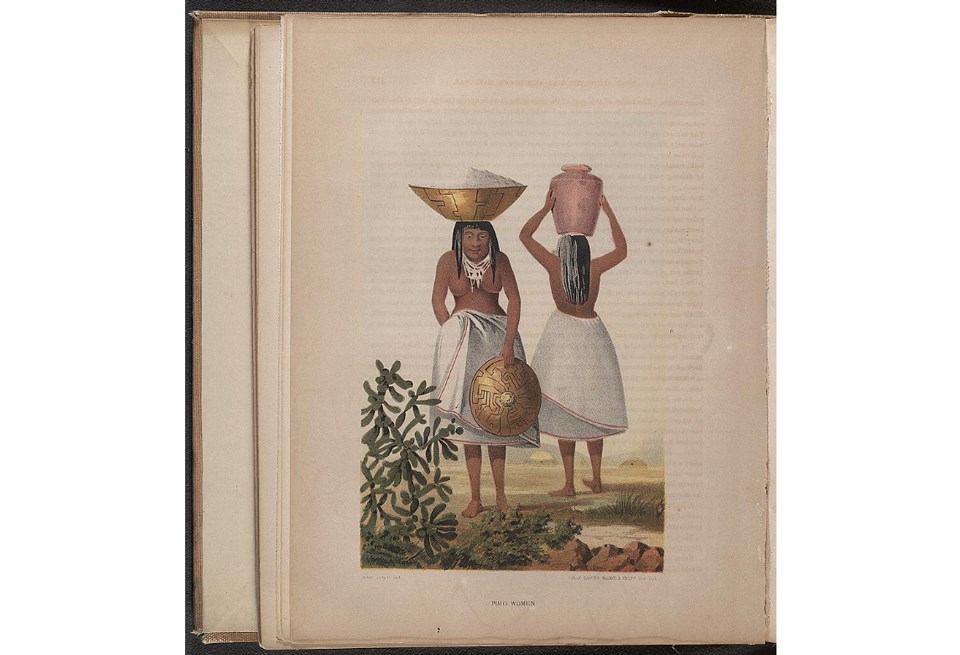

Gender is defined not by what people are, but rather by what they do, through distinctive activities, clothing, gestures, and postures. Gender functioned as a nonverbal communication tool for interactions between indigenous communities and their European counterparts. But the ways that these groups understood gender were very different.

In both native and European cultures, men were the official leaders. For Europeans, society was built upon gender and honor systems. Gender determined relationships and power in politics, economics, and social relationships. Social, cultural, economic, religious, and political life was also organized along gender lines in all indigenous societies of the Pimería Alta. In O’odham, Yoeme, and Nde traditions, religious and political leadership was passed down through male family lines. The same was true for the Spanish.

However, in O’odham and Yoeme societies, male religious and political leadership functioned within female-centered social systems. Households fell under the authority of the mother’s family line. Women controlled several key parts of society; they delegated use of agricultural goods, made rules about the division of labor within their families, and did most of the establishing of social relationships with outside groups.

Upon arrival in a new territory, Spanish missionaries needed to establish a relationship with the local residents. All parties agreed: political meetings between indigenous and Spanish colonists would be officially handled by men. However, for the O’odham, ritual and unofficial facilitation of meetings was primarily controlled by women. O’odham women traditionally established whether an unknown party was peaceful or not. An example of this occurred on November 1st, 1775 when Franciscan priests encountered O’odham along the Gila River. To greet the priests, the O’odham lined “up in two files, men on one side and women on the other, and as soon as we got down they all came in turn to greet us—our commander and the three Fathers—and shake our hands, first the men and then the women, big and little, displaying a great deal of happiness at seeing us by setting their hands on their chests, naming God and giving other utterances of goodwill; and this audience lasted a long while, since nearly all of them greeted us by saying Dios ató m’ busibóy just as the Christian Pimas of Pimería Alta, meaning ‘God give us, ourselves, help.’”

This encounter suggests that native visiting parties included women and children in order to emphasize their peaceful intentions. For the Spanish, negotiations of power and of peace tended to use only male interactions.

The fact that native women were so foundational for political talks to even begin was quite the surprise for Europeans. This fact even became problematic for colonial expeditions into the Pimería Alta because they often included only men. There was no way for them to offer the sign of peace native communities relied on—women. Unsurprisingly, O’odham, Yoeme, and Nde people noted the strange absence of women in Spanish expeditions. Did this mean the newcomers had hostile intentions? The two groups not only lacked a shared language, but a shared symbolism, which made it difficult for the Spanish to initially establish a foothold in the region. They arrived in large, heavily armed parties, presenting an alarming appearance of potential hostile force. Spanish and European men had to seek out other avenues, symbols, or gestures, to express their non-hostile intentions.

Last updated: April 15, 2021