Last updated: August 30, 2021

Article

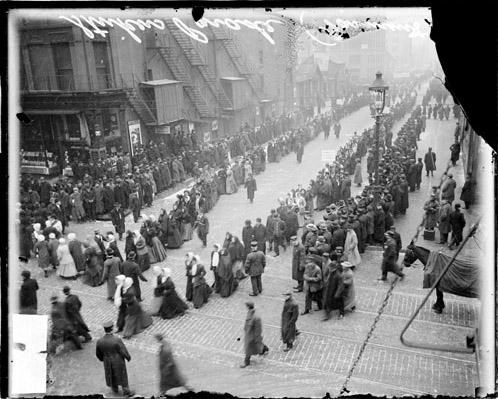

Women of the 1910 Chicago Garment Workers' Strike

Courtesy Library of Congress, https://loc.gov/resource/cph.3b07373/.

The content for this article was researched and written by Jade Ryerson, an intern with the Cultural Resources Office of Interpretation and Education.

When sixteen young women walked out of Hart, Schaffner, and Marx’s (HSM) Shop No. 5, they launched what became one of the biggest strikes in Chicago history. The 1910 garment workers’ strike lasted from September 22 until February 1911. At its peak, the walkout involved over 40,000 mostly immigrant laborers throughout the city. Tensions over low wages, inconsistent shifts, high production quotas, and unsafe working conditions had been brewing for a long time. At first, some male garment workers and the United Garment Workers of America (UGWA) were reluctant to support a woman-led strike. Even with assistance from the unions, tensions continued to rise. After almost five months of growing distrust, leaders finally secured a deal.

Located at 18th and Halsted Streets, Shop No. 5 is now a contributing property in Pilsen Historic District. The historic district was listed in the National Register of Historic Places in 2006. Here are some of the strikers’ stories.

Public domain.

Hannah Shapiro

When Hannah “Annie” Shapiro led the original walkout at Shop No. 5., she was 18 years old. Like most HSM employees, she was an immigrant. She had been born in Ukraine. As her parents’ eldest child, Shapiro joined the workforce when she was 13 to help support her family. She performed various jobs in the garment industry, such as making bowties and removing temporary stitches in men’s coats. Shapiro had once earned her highest wage, $12 per week, while operating a pocket cutting machine.

But in September 1910, Shapiro’s weekly earnings totaled only $7. She and the other garment workers earned 4 cents per piece of clothing, sewing pockets on men’s trousers or jackets. Things reached a breaking point when HSM cut pay by ¼ cent and introduced a bonus system that demanded high production rates. On September 22, Shapiro finally had enough and walked out. Years after the strike, she recalled: “We all went out; we had to be recognized as people.”

Anna Rudnitsky

Is it possible to be too good at your job? For 16-year-old Anna Rudnitsky, the answer was yes. Rudnitsky worked at HSM’s Shop No. 11, sewing men’s garments. Because the company paid workers per piece of clothing, working efficiently could pay off. But Rudnitsky’s foreman pressured her to sew more slowly and keep her pay down. Rudnitsky looked for work elsewhere but realized that conditions in other shops were not any better. When the garment workers’ strike began, she led 300 young women to join the walkout.

In 1912, Rudnitsky published an article in the magazine Life and Labor, in which she expressed her concerns about overworking. “What bothers me most is time is passing,” she explained. “Time is passing and everything is missed. I am not living, I am just working.” Because Rudnitsky hoped to enjoy life outside of work, she urged her readers to join labor unions and the WTUL. She believed that workers could secure shorter workdays and living wages through union activities.

Clara Masilotti

Born in the United States, Clara Masilotti came from an Italian immigrant family. She began working in the garment industry when she was 13 but switched jobs frequently due to disputes with supervisors. For instance, she recalled that one employer “preferred Italians, Jews, all nationalities who can’t speak English” because “they work like the devil for less wages.”

In 1910, Masilotti worked at an independent garment shop. Now 17 years old, she was asked to become a foreman to teach the “greenhorns,” or new employees. Masilotti received the promotion but was later demoted after she refused to inform employees that the company was cutting their wages.

Although Masilotti did not work at HSM, she played a role in the walkout. She and the greenhorns joined the strike after hearing union organizers whistling and picketing outside the shop where they worked. During the strike, Masilotti became a staff worker for the WTUL. In this role, she helped Italian immigrant workers to learn English.

Courtesy of the Kheel Center for Labor-Management Documentation and Archives, Cornell University. https://www.flickr.com/photos/kheelcenter/5279767738/.

Bessie Abramowitz

After immigrating to the United States when she was 15, Bas Sheva “Bessie” Abramowitz Hillman got a job sewing buttons. At the sweatshop, employees earned only $3 for a 60-hour work week. Abramowitz objected to the low pay and dismal working conditions. To voice her grievances, she organized a union-led shop committee, but was quickly fired and blacklisted.

Using a fake name, Abramowitz got a job at HSM’s Shop No. 5 where she continued to work until the 1910 garment workers’ strike. Now 21 years old, Abramowitz was one of the original sixteen strikers. She became a member of the strike committee and WTUL organizer. During the strike, she also met her husband Sidney Hillman. They were both militant labor activists and co-established the Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America in 1914. Abramowitz was the first woman appointed to the union’s general executive board.

The Strike

A walkout of this size was no small task to organize and implement. At the time, the men’s garment industry was the biggest employer in Chicago. Over two-thirds of the laborers were immigrants and about half were women. They often worked long or inconsistent shifts in cramped sweatshops with poor lighting. Working conditions, production quotas, and shift-lengths depended on the whims of foremen. Although HSM paid better than other companies, the pay scale also varied widely. Wages depended on the skillsets and physical demands required for different jobs. Hand sewers—generally women—were paid the least. Employees who operated cutting machines earned the highest wages.

Because the walkout began spontaneously, it took weeks to gain momentum. The strike initially lacked leadership and direction. Most of the strikers were immigrants who spoke only Yiddish, Polish, Russian, Italian, or German. This made it difficult to organize across ethnic groups. Additionally, some male garment workers refused to take a walkout led by women seriously. The poor pay and conditions eventually motivated them to join the ranks and participate as strike leaders.

Courtesy Chicago History Museum, via Jane Addams Digital Edition. https://digital.janeaddams.ramapo.edu/items/show/7151.

Support from the UGWA and Women's Trade Union League (WTUL) helped to overcome those challenges. After one month of disregarding the walkout, the UGWA called for a general strike. This led to increased support from other unions and industries. Within a week, HSM executives met with the UGWA to negotiate an agreement. When strikers rejected the deal, the WTUL and Chicago Federation of Labor (CFL) pledged their support. These three organizations provided leadership through a Joint Conference Board and strike committee. Seasoned reformers from the WTUL also organized relief and assisted with publicity and picketing.

As the strike dragged on, tensions rose between workers, local authorities, and the unions. Strikers, strikebreakers, and the Chicago police clashed in the streets. Other violent incidents erupted as strikers left meetings, picketed, or attacked strikebreakers themselves. The UGWA finally withdrew its support after strikers rejected another proposal in December. The WTUL urged them to settle and HSM agreed to arbitration. Local labor leader Sidney Hillman and famed defense attorney Clarence Darrow finally arranged a deal.

In mid-January, strikers began returning to work. Promises of grievance procedures and better wages and conditions made some workers hopeful. Yet, many remained unsatisfied, since employers refused to require workers to become union members. Twenty thousand garment workers continued to strike until February 18. Chicagoans also resented the UGWA’s initial disinterest, eventual abandonment, and lackluster agreement. Within a few years, labor leaders, including Hillman and Bessie Abramowitz, eventually left the UGWA. They established the new Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America in 1914.

Bibliography

Grossman, Ron. “And the women shall lead: Female laborers led the charge in Chicago’s massive garment workers strike of 1910.” Chicago Tribune. January 17, 2019. https://www.chicagotribune.com/opinion/commentary/ct-perspec-flashback-garment-strikers-abramowitz-hillman-012019-story.html.

Rudnitsky, Anna. “Time is Passing.” Life and Labor: A Monthly Magazine 2, no. 4 (April 1912): 97. Accessed February 14, 2021. https://hdl.handle.net/2027/coo.31924069101354?urlappend=%3Bseq=121.

Sive-Tomashefsy, Rebecca. “Identifying a Lost Leader: Hannah Shapiro and the 1910 Chicago Garment Workers’ Strike.” Signs 3, no. 4 (Summer 1978): 936-939. https://www.jstor.org/stable/3173136.

U.S. Department of Labor. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Wages and Hours of Labor in the Cigar and Clothing Industries, 1911 and 1912. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1913. https://hdl.handle.net/2027/uc1.32106020334204?urlappend=%3Bseq=27.

Weiler, N. Sue. “The Uprising in Chicago: The Men’s Garment Workers Strike, 1910-1911.” A Needle, a Bobbin, a Strike: Women Needleworkers in America. Edited by Joan M. Jensen and Sue Davidson. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1984. https://temple.manifoldapp.org/read/a-needle-a-bobbin-a-strike-women-needleworkers-in-america/section/6f10c237-0c36-4ba3-972a-92c8bf2c201a#ch4.

Women’s Trade Union League of Chicago. Official Report of the Strike Committee: Chicago Garment Workers’ Strike, October 29-1910 – February 18, 1911. Chicago: Women’s Trade Union League, 1911. Accessed February 12, 2021. https://hdl.handle.net/2027/inu.32000014247136.