Last updated: September 8, 2021

Article

William R. Wagner Oral History Interview

NPS

ORAL HISTORY INTERVIEW WITH WILLIAM R. WAGNER

AUGUST 21, 1991

HOUSE SPRINGS, MISSOURI

INTERVIEWED BY JIM WILLIAMS

ORAL HISTORY #1991-24

This transcript corresponds to audiotapes DAV-AR #4376-4380

HARRY S TRUMAN NATIONAL HISTORIC SITE

NATIONAL PARK SERVICE

UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR

ii

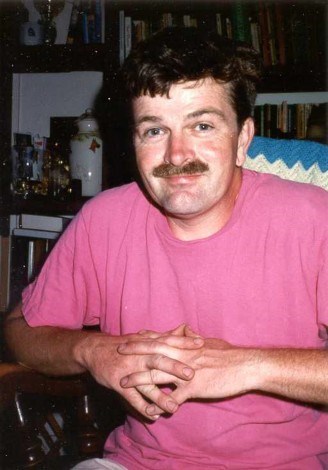

William R. Wagner

August 21, 1991

(National Park Service photo 322.9)

iii

EDITORIAL NOTICE

This is a transcript of a tape-recorded interview conducted for Harry S Truman National Historic Site. After a draft of this transcript was made, the park provided a copy to the interviewee and requested that he or she return the transcript with any corrections or modifications that he or she wished to be included in the final transcript. The interviewer, or in some cases another qualified staff member, also reviewed the draft and compared it to the tape recordings. The corrections and other changes suggested by the interviewee and interviewer have been incorporated into this final transcript. The transcript follows as closely as possible the recorded interview, including the usual starts, stops, and other rough spots in typical conversation. The reader should remember that this is essentially a transcript of the spoken, rather than the written, word. Stylistic matters, such as punctuation and capitalization, follow the Chicago Manual of Style, 14th edition. The transcript includes bracketed notices at the end of one tape and the beginning of the next so that, if desired, the reader can find a section of tape more easily by using this transcript.William R. Wagner and Jim Williams reviewed the draft of this transcript. Their corrections were incorporated into this final transcript by Perky Beisel in summer 2000. A grant from Eastern National Park and Monument Association funded the transcription and final editing of this interview.

RESTRICTION

Researchers may read, quote from, cite, and photocopy this transcript without permission for purposes of research only. Publication is prohibited, however, without permission from the Superintendent, Harry S Truman National Historic Site.iv

ABSTRACT

William R. Wagner served as a naval corpsman who assisted Harry S Truman from 1970 until Truman’s death in 1972. Wagner discusses the daily routine, those involved, and the use of the house during his tour of duty in the Truman home in Independence, Missouri. Wagner then related his subsequent activities including attending Harry S Truman’s funeral, a later visit with Bess W. Truman, gifts given to him by both of the Trumans, and Bess W. Truman’s assistance in his enrollment at the University of Missouri–Columbia.Persons mentioned: Donald Nauser, Harry S Truman, David Bagley, James Rowley, Paul Burns, Jerry W. Crunk, Scott M. Boehm, Charles F. Rowe, Bess W. Truman, Mike Westwood, Ronald Reagan, Margaret Truman Daniel, Arletta Brown, Edward Hobby, May Wallace, Ardis Haukenberry, E. Clifton Daniel, Jr., Wallace H. Graham, Richard M. Nixon, Ruth Spence, Bill Crisp, Frank Jack Fletcher, and Dwight D. Eisenhower.

ORAL HISTORY INTERVIEW WITH WILLIAM R. WAGNER

HSTR INTERVIEW #1991-24JIM WILLIAMS: This is an oral history interview with William Wagner. We’re in House Springs, Missouri, on August 21, 1991. The interviewer is Jim Williams from the National Park Service. Scott Stone from the National Park Service is running the recording equipment.

Well, I need to get a little bit of background before we get to the Truman relationship, really. Are you a native Missourian?

WILLIAM WAGNER: No, I’m an Ohioan, straight off there.

WILLIAMS: And I understand you were in the Navy. How did that come about, and when?

WAGNER: When did I go in the Navy? Let’s see, I was attending the Ohio State University, and back in 1969 I decided at that time to relinquish my education and go into the service, and that’s when I started.

WILLIAMS: Were they still drafting people at that time?

WAGNER: They were, yeah.

WILLIAMS: But you weren’t?

WAGNER: No, I wasn’t part of that. I just decided that I needed a break.

WILLIAMS: Why did you pick the Navy?

WAGNER: I thought it was the best.

WILLIAMS: Were you on ships?

WAGNER: No, I was a dry-land sailor for all four years. I had my training down in Orlando, Florida, then up to Great Lakes for training for a corpsman, and

6

then from there went to Bethesda, Maryland.

WILLIAMS: What was your association with the Trumans?

WAGNER: I was their medical aide.

WILLIAMS: How did that come about?

WAGNER: One day I was asked to see the CO, and I was working on a ward, what they called VIPs. It was for the congressmen and senators and high officials of the military of all branches, and I was called down to the CO and I was informed that they would like to have me out in Independence, Missouri, to pack my bags and go.

WILLIAMS: What was your reaction?

WAGNER: [chuckling] I probably didn’t have one. I just said, “Oh.” It was nerves, basically, and quite honored at that time to be selected.

WILLIAMS: Could you have refused?

WAGNER: I don’t know. [chuckling] I don’t know if you could have or not. It happened so fast, and I was . . . I guess that was like in the evening, just before I got off duty, or was off duty and asked to come down to the CO. And within two hours, I was given my discharge papers and had everything packed, and six o’clock the next morning, they made sure I was up and got into my car and started driving. I remember there was a big blizzard, driving from D.C. I drove up to Cleveland, and it usually just takes six hours, it took twelve hours to get up there. But there was no other way to get over to . . . from D.C. over to Independence, anyhow, so I drove up to Cleveland. And that’s where my family was, and spent the night there and drove on and stopped in Indiana, and drove on to Kansas City the next

7

morning.

WILLIAMS: I guess this was in the wintertime?

WAGNER: Right, in January.

WILLIAMS: January of 19 . . . ?

WAGNER: Seventy-one.

WILLIAMS: What did you know about the Trumans before even this all came about?

WAGNER: That he was a President of the United States and he lived in Independence, Missouri. [chuckling]

WILLIAMS: That’s it?

WAGNER: Yes.

WILLIAMS: You had no preconceived notions about what it was going to be like?

WAGNER: No, I didn’t. I didn’t even know what the state of Missouri really looked like. I thought it was going to be cornfields and cornfields and wheat fields, and that was the extent of it.

WILLIAMS: Was there any preparation at all? They just said, “Pack your bags and go”?

WAGNER: No, they wanted to know . . . Well, they knew my background was in medicine because I had a few years of experience before I even joined in the military. And then the year and a half training up on that ward, and I did have some thoracic surgery nursing, and I like geriatric nursing, and . . .

WILLIAMS: Was this something the Navy does a lot for former presidents?

WAGNER: I really don’t know. It was my first experience involved with it, and I don’t know how other branches are involved. At that time, I knew I was like the second or third corpsman going with the president.

WILLIAMS: You weren’t the first one there?

8

WAGNER: No, there was a Chief Donald Nauser that was there before I arrived, and I was asked to come after President Truman became ill and was in the hospital. Then he was waiting for me to get out of the hospital so he could come home.

WILLIAMS: How were your duties described to you? Well, why were you there?

WAGNER: To assist with the needs of President Truman in any medical form, you know, in any medical form that I knew how or would be learning.

WILLIAMS: So you were basically on call to assist in any way?

WAGNER: Yes.

WILLIAMS: Were you the only one there, only corpsman there at one time?

WAGNER: There was one corpsman on per shift. There was two other ones for about a year after . . . Well, I guess, no, it was longer than that. No, it was shorter. It was probably three months that it was just Donald Nauser and myself, and we were doing our twelve-hour shifts, and the Navy decided that we should have more flexible hours, a little bit more time to ourselves, and so two more were brought along so we could have like swing shifts and things like that.

WILLIAMS: And days off.

WAGNER: Right. And it worked out real well then.

WILLIAMS: So there were four, maximum?

WAGNER: Right. Another person came on at the very end, but he was there for a very short period of time, because that was at the very end of our tour and before Mr. Truman passed away. There were two other ones that were there like almost two weeks, and it was all gone then, because we knew

9

that this was going to be probably the last time he would be out of the hospital.

WILLIAMS: Do you remember the names of the other two that came?

WAGNER: I can get you the names. Just take this off. [unhooks his microphone]

WILLIAMS: Do you have a scrapbook or something?

WAGNER: Yeah, I’ve got . . . Oh, I’ve got scrapbooks. [chuckling] You’ve probably seen all these photographs. All this. These were the orders that I had.

WILLIAMS: What is an HM-2?

WAGNER: That’s hospital corpsman, second class.

WILLIAMS: So could you just describe what these are?

WAGNER: Well, these are letters of gratitude, and this was from Vice Admiral David Bagley. And let’s see, this one is from whom? Well, this is to Vice Admiral David Bagley, and this is from James Rowley. He was the director of the Secret Service at that time, and he was just informing our officers in charge, or what do you call them? COs that—

WILLIAMS: Could you read that so we’ll have it on tape?

WAGNER: Sure. [reading] “Vice Admiral David H. Bagley, Chief of Bureau of Personnel, U.S. Navy Department, Washington, D.C. Dear Admiral Bagley: I wish to take this opportunity to express the sincere appreciation of the United States Secret Service for the excellent cooperation and assistance provided by five Naval corpsmen in connection with the long illness and hospitalization of Former President Harry S. Truman. Special Agent in Charge Paul A. Burns, of our Truman Protection Division, has told me that each of the corpsmen handled his assignment with exceptional

10

efficiency and discretion. Those corpsmen we wish to single out are: Hospital Corpsman Chief Donald R. Nauser; HM-1 Jerry W. Crunk; HM-2 Scott M. Boehm; and HM-2 Charles F. Rowe; and HM-2 William R. Wagner. The Secret Service is grateful to each of these men. They are sincerely commendable. Sincerely, James J. Rowley, Director.”

WILLIAMS: So we have all the spellings, let’s see . . . I know we have Nauser’s name, and Jerry W. C-R-U-N-K; Scott Boehm, B-O-E-H-N; Charles Rowe, R-O-W-E; and it’s Admiral Bagley, B-A-G-L-E-Y. And Director Rowley, R-O-W-L-E-Y. This was February 22, 1973. And there’s another one from somebody in the Navy.

WAGNER: Yes, it’s from Chief Bureau of Medicine and Surgery, to HM-2 William Wagner, via Commanding Officer, Naval Hospital, Long Beach, California. A letter of appreciation. [reading] “I wish to express my appreciation for your professionalism and the outstanding performance while assigned duty as a Hospital Corpsman serving Former President Harry S. Truman, his wife, and staff in Independence, Missouri, from February 1971 to January 1973. Such an assignment must by its very nature demand of the medical department representative the very highest standards in deportment, niceties of manner, [impeccable] dress, military bearing, courtesy and professional competence. You have, by your performance of duty, met this criteria. Such performance and devotion to duty enhances the reputation of all hospital corpsmen everywhere, and you can take great pride in your accomplishments during this tour of duty. Your service in this capacity has been in the best tradition of the Hospital Corps

11

and the Navy Medical Department. I wish you every success in your future Navy career and extend my personal congratulations for a job well done. A copy of this will be made part of your permanent record. G.M. Davis.”

WILLIAMS: How much contact did you have with the Secret Service?

WAGNER: Well, there was a house across the street that we kind of signed in at in the beginning, and . . .

WILLIAMS: Would you stay over there during your shift?

WAGNER: Only during the daylight hours we’d be over there, so we would not disrupt their personal activities in the house. If it was warranted, they would ring a buzzer or call us over for any emergencies or any special care.

WILLIAMS: If you were on the night shift, where would you stay?

WAGNER: In the residence itself.

WILLIAMS: Whereabouts?

WAGNER: Well, President Truman slept downstairs, so we would be in the bedroom or right outside the bedroom itself.

WILLIAMS: In the living room?

WAGNER: Yes.

WILLIAMS: I suppose you had security clearance. What was involved in that?

WAGNER: Fill out a lot of forms and wait for the results.

WILLIAMS: And you said you were fingerprinted?

WAGNER: Fingerprinted with the Independence Police Department, Secret Service.

WILLIAMS: And you arrived in ’70, early ’70?

WAGNER: Seventy-one.

WILLIAMS: Seventy-one. So you were there about two years, almost.

12

WAGNER: Two years, right.

WILLIAMS: How would you describe Mr. Truman when you arrived, in general terms?

WAGNER: Well—

WILLIAMS: Was he walking?

WAGNER: Oh yes, he was very coherent and he was able to walk. At that time, an eighty-six-year-old person, he did quite well, of course with his cane, and he was a very interesting individual to speak with.

WILLIAMS: Do you remember your first . . . Would you go over and just visit with him?

WAGNER: We’d visit. Well, I was taken over there and visited with him, and we talked. But on a daily basis when he was retiring, it would be in the evening. I’d go over there and we’d sit around and talk for a while, and then it was time for him to get ready for bed and assist him.

WILLIAMS: Did you talk about the military, being in the military?

WAGNER: Not very much. It was basically books, a little bit of his personal life and knowing about his family, and my family, day-to-day news that was going on at that time.

WILLIAMS: What kind of person would you describe him as being?

WAGNER: [pause] Well, you can call him typical, but not typical. Say, an atypical type grandfather person, stern but interesting. He gave you a warm feeling when you walked in the room. It was not degrading or anything like that. He had respect for you and you gave him respect back, and it was very . . . And the same with Mrs. Truman. She enjoyed people. And like you were coming from the outside and informing them of what was going on, so it was an

13

experience. So you had to make sure what was going on in the world to tell them. They did read newspapers and had radios, but they always wanted to have someone else’s viewpoint. And they were both great readers and made you interested and made you use some of their library books to read. And that was quite enjoyable also, because one-of-a-kind type books, too.

WILLIAMS: Did they want you to be there, or was this something that was foisted upon them by their doctors or somebody? Do you know?

WAGNER: I think Mrs. Truman accepted it and was pleased that we were around. We did not try to be overpowering. And we were there because there was a need, and I don’t think we would have been there if there wasn’t a need. I think that’s the way the Trumans would have wanted it. They did not like to abuse outside services.

WILLIAMS: When you got there, were you really needed on a day-to-day basis, or was it just in case there was a need for you?

WAGNER: It was more just in case there was an emergency or he needed something, so we kept a very low profile. And at night we were there, just in case something happened in the middle of the night.

WILLIAMS: So it was more of a preventive . . .

WAGNER: Precautionary measure, yeah, so we didn’t have to call the ambulance service or something like that and someone unknown. They wanted to make sure that if somebody was going to work with him, it was somebody they already knew.

WILLIAMS: Who was your boss, really, outside of Don Nauser, I guess, who was in charge of the Navy people. Did you take directions from their doctor?

14

WAGNER: Well, we’d never seen much of the doctor until he went into the hospital. For medical things, it would have been from the doctor, if he wanted us to do any special care. Donald Nauser worked the day shift, and so if anything came from the doctor, we would all be informed through Mr. Nauser. And if it came through the military, that would be from the Naval Reserve Office in Kansas City. But we didn’t have that much feedback from that branch. We were there, but we did not do much with them.

WILLIAMS: Just kind of on your own?

WAGNER: Yeah. I think the Secret Service probably kept a closer eye on us. I mean, you felt like they were there. They weren’t watching you or anything, it was quite open, but if you were going to leave any great distance, they wanted to know where you were going to be, how long you were going to be gone, numbers to be reached at and that, which didn’t bother me at all.

WILLIAMS: Where did you live at this time?

WAGNER: I lived at 801 North Main, at a house with Mr. and Mrs. Fisk. He used to be a Supreme Court Justice for the state, and he has passed away about five, six years ago. Mrs. Fisk still lives there. And I lived there for almost the full two years.

WILLIAMS: Did they want you to live close by?

WAGNER: I don’t think there was any real restrictions on where we lived, but I think the three corpsmen decided to live within walking distance. Mr. Nauser lived in Blue Springs, Missouri, but I probably lived the farthest away of walking distance. I probably lived maybe six blocks.

WILLIAMS: So you would walk to work?

15

WAGNER: Most of the time, yeah. In inclement weather, drive a car over, but most of the time it was a nice walk.

WILLIAMS: And first thing, you would check in at the Secret Service house?

WAGNER: Right. It was better to work through them than work against them. It was just a lot easier, and they were pleasant people. There wasn’t any problems. We all had jobs to do, and we all tried to work together.

WILLIAMS: Did you always work the night shift?

WAGNER: No, we broke it up into three shifts: basically, 7:00 to 3:00, 3:00 to 11:00, and 11:00 to 7:00. And then on weekends we did a twelve-hour shift so someone could at least have time off.

WILLIAMS: So you would rotate shifts?

WAGNER: Right.

WILLIAMS: Did you have a favorite shift?

WAGNER: Oh, a favorite shift?

WILLIAMS: Was it better to be in the house at one time over another?

WAGNER: If I was going to work, I would rather work the 3:00 to 11:00 shift because then you had more contact with the Trumans, and I enjoyed that probably the most.

WILLIAMS: When would he get up?

WAGNER: Let’s see, right around 7:00. Right around seven o’clock in the morning.

WILLIAMS: Pretty early.

WAGNER: Yes. Mrs. Truman would probably get up first and announce that she is up; and then we would probably wake him up, or he already had his own built-in alarm clock that it was time to get up.

16

WILLIAMS: Was she still upstairs?

WAGNER: Yes.

WILLIAMS: Did you ever go upstairs?

WAGNER: Only one time.

WILLIAMS: Did you know which bedroom she was using?

WAGNER: No. I guess, if I walked upstairs, I probably would be able to know which one it was.

WILLIAMS: We have some pictures. Maybe one will look familiar.

WAGNER: Because most of the time she would be over the bannister.

WILLIAMS: Hollering down.

WAGNER: Yes. So I really didn’t know what was going on upstairs.

WILLIAMS: How active, how much did Mr. Truman get out when you first arrived in ’71?

WAGNER: Well, since it was wintertime, we waited until spring. He did take his weekend drive in the car with his private driver. I think his name was Don. I don’t remember for sure.

WILLIAMS: Was it Mike Westwood?

WAGNER: That could have been it, Mike Westwood, yeah. And I guess he was a retired policeman from Independence.

WILLIAMS: Right.

WAGNER: And they would go out on their weekend drive, and we would follow.

WILLIAMS: In another car?

WAGNER: Right.

WILLIAMS: Everywhere he went, you would follow him?

17

WAGNER: There would be a Secret Service and a corpsman, just in case something. . .

WILLIAMS: That’s pretty elaborate.

WAGNER: But it was very low profile. You know, it wasn’t that we were right on their back bumper, and if somebody was driving faster and got between us, there wouldn’t be anything that drastic. It was very low profile.

WILLIAMS: I guess they do that with the president, the acting or reigning president.

WAGNER: Well, yeah, it’s a little bit more tighter. I mean, they would block off streets and everything else. Especially, I think it was . . . Which president came down here? It had to be Reagan.

WILLIAMS: To St. Louis?

WAGNER: It had to be Reagan. That was real tight. And I think two of us were on duty during that period of time. Just because if . . . you know, something happened by outside means.

WILLIAMS: Do you recall where you would drive?

WAGNER: Anywhere. It was basically out in the country. One time we went out to see . . . I guess it was his sister who lived . . . Where did she live?

WILLIAMS: In Grandview?

WAGNER: Yeah. You’re more up with it.

WILLIAMS: Down south. That was Mary Jane?

WAGNER: Mm-hmm.

WILLIAMS: Did you ever meet her?

WAGNER: No.

WILLIAMS: You’d just stay—

WAGNER: We did not really socialize or be introduced, except to Margaret and her

18

family, the two boys.

WILLIAMS: So these drives would be mostly in the country. You wouldn’t go downtown Kansas City or anything?

WAGNER: No, there was really no need to. I mean, most of their needs and wants were handled via phone or by other means. We’d take a few walks around, but the drives were to country or just to drive around.

WILLIAMS: Just to get out of the house.

WAGNER: Just to get out of the house, right.

WILLIAMS: Would he go to the barbershop or anything like that? To lunch with anyone?

WAGNER: No, the barber would come in, I believe, and lunch would be served there. Mrs. Truman went out and got her hair done. I think there was a barber that came in, but I guess it was always done when I wasn’t on the shifts. It was probably done during the week.

WILLIAMS: Did they have much company?

WAGNER: No, not that much. Not much at all, really. See, most of the activity would be being done during the 7:00 to 3:00 part, and that’s when Don Nauser was on, so we really didn’t know what was . . . And if he was off on vacation or something else, we didn’t see that much activity. Very few people would be in the house.

WILLIAMS: Were there other staff in the house besides Secret Service, the Navy corpsmen?

WAGNER: Their maid. Let’s see, was that Arletta?

WILLIAMS: Vietta? Or Arletta Brown?

19

WAGNER: Yeah, Arletta, I believe her name was, and she was in the house. I guess she did some of the cleaning, too.

WILLIAMS: Did they have a yard man?

WAGNER: There was . . . they always called him “the preacher.” I never knew his name. He was referred to as “the preacher.” An elderly gentleman that cut the grass and trimmed the shrubs, and that was it.

WILLIAMS: So basically those two people?

WAGNER: I don’t know of anybody else. Yeah, that was the only staff people.

WILLIAMS: Did the relatives that lived nearby ever come over?

WAGNER: Well, Bess’s sister, Mrs. Wallace, she was over there—you know, of course, just walk across.

WILLIAMS: Did you get to know her?

WAGNER: No, never met her. Just via camera, you know, and she would always wave at the cameras like she was coming across. [chuckling]

WILLIAMS: What about Mrs. Haukenberry who lived across Delaware in the big Victorian?

WAGNER: I don’t . . .

WILLIAMS: She was a second cousin of Mr. Truman.

WAGNER: I didn’t see any communications or any visitations by her. It was very quiet.

WILLIAMS: Was there a set routine, time set out? We have lunch always at this time, dinner at this time . . . ?

WAGNER: Lunch was . . . well, I think it was right at noon.

WILLIAMS: Where would they eat?

20

WAGNER: Depending on the weather . . . Breakfast was always at the main dining room. I think all meals were at the main dining room. I think if it was real good weather, they’d go have lunch out on the screened-in porch in the back, and then spend time back there.

WILLIAMS: Was Mrs. Truman basically in charge of what went on in the house?

WAGNER: Definitely, yes. The house was hers. And she was very easy to work with. Explained to her what was going on or what you would want to do and get permission, and she would give you the okay or change our plans somehow. But she was very, very easy to work along with.

WILLIAMS: So you made sure you checked things with her?

WAGNER: Oh, yes. Even, you know, if they were going to go out and special clothing was going to be permitted, she would select the clothing. And she would make sure that he would be going to bed at the proper times or . . .

WILLIAMS: Which was what time?

WAGNER: I guess it was about 8:00, 9:00 . . . about nine o’clock. But he really wouldn’t go to bed. We would talk for a while in the bedroom, and then he’d say, “Well, I guess we’ve got to be quiet now or she’ll hear us.” [chuckling]

WILLIAMS: How did he talk about her?

WAGNER: “The Madam” or “The Missus.”

WILLIAMS: Did he ever call her “The Boss”? Because that’s how most people think of him as referring to her.

WAGNER: No. You know, I heard “ma’am” and “Mom.” But it was very, very typical: an older couple–type relationship.

21

WILLIAMS: How did she refer to him?

WAGNER: Harry or Dad, I think it was.

WILLIAMS: She wouldn’t say “The President”?

WAGNER: No. If she was speaking to us, I guess she would never come out and say “The President.” “How is he this morning?” and “Did everything go all right?” So it was always referred that she was talking about him.

WILLIAMS: But it wasn’t, “I’ve been speaking to the president, and he wants this,” or anything?

WAGNER: No. No, we always addressed him as “Mr. President” and her as “Mrs. Truman.”

WILLIAMS: Where would he spend most of his time in the daytime?

WAGNER: In the library. In the library, reading, doing correspondence. The secretary, what was her name? She was at the library for a long time.

WILLIAMS: Rose?

WAGNER: Rose. They would communicate via telephone, or that would be another person that would be stopping by, to pick up any letters that had to be written, and . . .

WILLIAMS: Was she there about every day?

WAGNER: I don’t think so, no. They would probably make telephone calls to her, but I never met her.

WILLIAMS: Oh, you didn’t?

WAGNER: No.

WILLIAMS: Because you were on the night shift?

WAGNER: Well, you know, we didn’t want to make an issue out of it either, or try to

22

get to the library and say, “Hi, I’m Bill Wagner.” And we all kept pretty low profiles. The people that . . . you know, my landlord of course knew who I was doing and working with. People that I socialized outside of the Truman group, I just said that I was working with geriatric patients, and it was a lot easier. And basically that’s what the Secret Service did, or they were on special assignment. It was never brought up that they were working with the Trumans.

WILLIAMS: We need to change the tape.

WAGNER: Sure.

[End #4376; Begin #4377]

WILLIAMS: You mentioned books earlier and that you were allowed to read anything in the house. Do you remember anything in particular, what kinds of books there were?

WAGNER: Oh, there were all sorts. Mrs. Truman loved whodunits and he loved history. He took a fancy to the history.

WILLIAMS: What did you like?

WAGNER: I like history. I didn’t read too many of the whodunits. I never got involved in it. I love the history. There were so many books to pick from, and you just took one. His best-seller rack was in one location, and if he was finished reading it, he’d ask you if you’d like to read it, “and we can discuss it after,” which was kind of enjoyable. And he discussed his book, books, you know, his memoirs.

WILLIAMS: Do you remember what he said?

WAGNER: What he said was written in the books. And it was really true. How his

23

name was . . . you know, S didn’t have a period, it was just the S. We talked very little about the bomb. I think it was a subject that probably was on his mind always, and I think it was something he lived with. It was hard to talk to . . . to anybody, really.

WILLIAMS: When he was giving tours of the library still, he kind of had favorite subjects that he would talk about: the duties of the president, the role of the presidency. Did he talk in terms like that?

WAGNER: No, for myself, I did not bring up that subject very much. I didn’t know how touchy that would be, so I tried to keep it very open and nothing really down to the presidency and . . . It was just basically day-to-day talk. There were some times that we’d talk about Margaret, and the family were coming in, or the family was there.

WILLIAMS: When did you first meet her?

WAGNER: Let’s see. Well, I didn’t keep notes on that, but I think it was like early that spring.

WILLIAMS: Would it have been around his birthday, in May?

WAGNER: It could have been. She was there probably three or four times with the whole family, and then a couple times by herself.

WILLIAMS: How did she strike you?

WAGNER: Like a president’s daughter, probably. Very protective of mom and dad.

WILLIAMS: Was she interested in you, like the Trumans seemed to be?

WAGNER: No, we probably really stayed away much more. There was one occasion that I had . . . I guess it was a lunch with the president, and Mrs. Truman and Margaret were there, and it was just basic lunch and basic talk, but it

24

was not with her husband or the children. And that was an enjoyable time.

WILLIAMS: When she was there, did you change your routine at all?

WAGNER: We would stay in the background until we were asked to assist in any fashion.

WILLIAMS: Did she take over any of your duties of caring for him while she was there or anything?

WAGNER: No. No, she thought that we knew better, and if we needed assistance that we would call on her. But for the most part, we stayed in the background and waited for our cue.

WILLIAMS: And you met her husband?

WAGNER: Yes.

WILLIAMS: What was he like?

WAGNER: He was a quiet individual, as much as I remember of him. Just a quiet individual, and you didn’t hear much from him. Because the period of time that we were there, they would be in the other room and would prepare for the night or . . .

WILLIAMS: What about the grandsons?

WAGNER: They were typical children. You know, they wanted to run, they wanted to play.

WILLIAMS: Was that a problem?

WAGNER: No. They knew their limitations. Margaret informed them of their limitations. And if they wanted to get outside, they could play in the yard and things like that. But the kids usually didn’t stay that long, maybe for a couple days and they’d be gone again.

25

WILLIAMS: Were they curious about why you were there?

WAGNER: No. I guess they were pre-informed about the situation, and this is the way it was and everybody accepted it. I don’t remember any of the other corpsmen ever . . . I don’t think there . . . Well, the other corpsmen never brought up if they went over and talked with her, or anything else. But we were basically informed to stay as low-profile as possible if they had guests, and basically it was just Margaret.

WILLIAMS: And she stayed in the house when she was here?

WAGNER: Oh yes, she stayed upstairs.

WILLIAMS: And the whole family?

WAGNER: They were all there.

WILLIAMS: Somewhere.

WAGNER: Yeah, they all went upstairs.

WILLIAMS: Did you ever have any call to go in the basement or up in the attic for anything?

WAGNER: I went up the steps one time, I can remember, and down in the basement maybe a couple times, but not much more than that.

WILLIAMS: What do you remember about the basement?

WAGNER: Well, they used to cure their meat down in the basement. I remember that. They had hams and sides of beef, and they were curing down there.

WILLIAMS: Hanging?

WAGNER: Hanging.

WILLIAMS: Did you have keys to the house, or was it always just open?

WAGNER: We had a key to the house, but it wasn’t necessary to use them. Each of us

26

were given a key, but we usually went through the back door.

WILLIAMS: The kitchen door?

WAGNER: Yes. Very, very few times, if it was real icy out the back, we’d go through the front door, but most of the time we went through the kitchen.

WILLIAMS: You said, if the Trumans needed you, they could buzz over. Were there . . .

WAGNER: There was an alarm that all they had to do was push. I never found out where the alarm was in the house. [chuckling] We had walkie-talkies and we could have done the same thing faster than we could have run over. The walkie-talkies had to remain on our bodies at all times.

WILLIAMS: They connected you with who?

WAGNER: To the Secret Service across the street.

WILLIAMS: So, if you were in the house, you could call right over.

WAGNER: Right.

WILLIAMS: And they would do whatever was necessary.

WAGNER: Mm-hmm.

WILLIAMS: When did you notice Mr. Truman changing, or did he change while you were there?

WAGNER: Changing? I think that just age finally came . . .

WILLIAMS: Gradual?

WAGNER: Yeah. There was nothing drastic going on. It was just, I think that you know, older people they just start, you know, withering away and it came his time. There was no shocks that he was going to go in the hospital—we felt as, with the doctor and the corpsmen felt that we’d probably get better care. We probably could have done everything to a certain degree, but we

27

thought at that time it was a lot better for him to go into the hospital.

WILLIAMS: When he went into the hospital, were you still on duty?

WAGNER: Oh yes, we remained with him. One of the corpsmen was with him all the time, and it was—

WILLIAMS: Was that in addition to the regular hospital staff?

WAGNER: There was a nurse in the room at the same time. She did all the care, and we were there for assisting . . . whatever they needed.

WILLIAMS: I was talking to somebody the other day who visited—I think it was in ’68 or ’69—and as he came in, Mrs. Truman told him, “Now, Harry’s a little hard of hearing and you’ll have to speak . . .” Is that basically the way he was? Oh, “and he slurs his words sometimes.” So apparently she would tell people to be prepared.

WAGNER: I don’t know if . . . I guess I took it for granted. Because with the background I had with geriatric nursing, I assumed a lot, that, you know, I am working with an elderly man, and I had it based on that first. I mean, yes, he was president, but he was also a real true human being. But it never bothered me. I mean, you know, if he slurred words, you’d just say, “I’m sorry, I didn’t hear you,” and repeat it. Or if he didn’t hear you, you spoke a little louder.

WILLIAMS: Did he ever use hearing aids?

WAGNER: Boy, you know, that’s something I can’t remember, because somebody told me he did have one, but I don’t remember ever . . .

WILLIAMS: Some people, they don’t use them if they have them—

WAGNER: Right. I don’t think he had one. I mean, if he did, he didn’t use it.

28

WILLIAMS: Did he ever get to the point where he couldn’t walk at all?

WAGNER: At the very end.

WILLIAMS: Did he use a wheelchair?

WAGNER: At the very end, just—

WILLIAMS: Right there in the last month or so?

WAGNER: Yeah. He was a strong individual.

WILLIAMS: All those years of walking, I’m sure, helped.

WAGNER: Yes. Oh yes.

WILLIAMS: Did he ever talk about regretting . . . The memory that a lot of people have is his walks, and it seems like if you couldn’t do that any longer, you might lament that. Did he ever seem angry or anything?

WAGNER: I think there was one time that he went out for a walk and there were strangers at the end of the road, and he really didn’t want to see strangers. And I think he probably just said, “Well, I guess I can’t go out for my walks unless we go somewhere else,” instead of his own yard. We would do walks . . . I remember a couple of times that we’d get dressed up and walk from one side of the house to the other, then back, and things like that, if we couldn’t go in the car or we didn’t want to take a chance of going out on the streets because of the hours and the amount of visitors that were coming up to the house.

WILLIAMS: So you’d walk outside?

WAGNER: Mm-hmm. But, you know, most of the time people wouldn’t even know that we were there, unless they were coming off to the other side of the house.

29

WILLIAMS: Were you in uniform?

WAGNER: No, we were in civilian dress—coat and tie.

WILLIAMS: Another way people wouldn’t recognize why you were there.

WAGNER: Right. We didn’t wear our uniforms at all.

WILLIAMS: Were the neighbors or people in Independence aware that he had this medical—

WAGNER: Oh yes. Oh yes. I think all the neighbors knew situations probably before anybody else did, and I think they assumed that, “Oh, well, there’s something going on in the house. Well, we’ll find out about it shortly.” But there was nothing, you know, really . . .

WILLIAMS: Did you get to know the neighbors, any of the neighbors?

WAGNER: No.

WILLIAMS: Were there ever any real emergencies where you had to call in?

WAGNER: No, not really. No, it really never came to that point.

WILLIAMS: Who decided like when it’s time to go to the hospital? Would that be Dr. Graham’s decision?

WAGNER: Yeah, Dr. Graham and Donald Nauser.

WILLIAMS: Mrs. Truman’s nurses, in her last few years, would read to her because, I guess, her eyes . . .

WAGNER: Mm-hmm. I visited Mrs. Truman maybe about three or four times, maybe more than that. But I would go in there for such a short period of time. I just wanted to let her know that I’m keeping in contact. I would write to her every once in a while, Christmas, her birthday. But that was basically as far . . . You know, there were a few times I called her, but she couldn’t

30

really hear me. And then when she was being more in a wheelchair, I felt guilty making her wheel to the telephone, so I thought it was a lot better just to stop.

WILLIAMS: Did you ever read to Mr. Truman like her nurses read to her?

WAGNER: No, it wasn’t necessary. I mean, he could read. Or there were times that he said, “Well . . .” you know, mentioned something, “Would you read this?” But nothing in great detail. Because he had pretty good vision, and then he had a large magnifying glass that, if he couldn’t read, he’d bring it up. It was a little . . . with a little light on it.

WILLIAMS: And usually that would be in the study, probably?

WAGNER: Right. In the bedroom, he would say, “Go out and get that book,” or something like that. I’d bring a book back and read for about ten or fifteen minutes, and that basically was it. He’d rather just talk.

WILLIAMS: Where there, what kind of beds were in that bedroom?

WAGNER: Two single beds.

WILLIAMS: Just regular poster . . . ?

WAGNER: Yeah.

WILLIAMS: She ended up having a hospital bed. There was never anything . . . ?

WAGNER: There were no hospital beds downstairs, no.

WILLIAMS: This is the way the house looked when we took possession in ’83, I guess it was.1

WAGNER: Mm-hmm.

WILLIAMS: These are the exterior ones. If you recognize anything different, please

1 Wagner and Williams view and discuss the Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS) photos of the

31

point them out, or anything familiar, or if it reminds you of a story. I guess you’d be walking on . . .

WAGNER: On the other side.

WILLIAMS: This side, the south side.

WAGNER: Yes. See, this was the living room door, and during the summer months we’d have this door open so we could talk with the Secret Service, what was going on.

WILLIAMS: So this door was used at times?

WAGNER: Very seldom, but that was used, and the president would walk out this door and come around the back, or would walk a little bit farther. He didn’t go out too much because he didn’t want the public to see him. He said, you know, he wanted to leave a good image.

WILLIAMS: The hat and coat are there by this door. Is that the door they would use like when you were going on drives?

WAGNER: Right.

WILLIAMS: And then come down the sidewalk to the driveway?

WAGNER: Right.

WILLIAMS: Was there an air conditioner in the bedroom, in the window? Do you recall?

WAGNER: I don’t think there was. I don’t remember.

WILLIAMS: Here’s the porch.

WAGNER: I don’t remember air conditioning, not at all. Well, there used to be vines all over here.

Truman home. These are available at the park for viewing.

32

WILLIAMS: I think they were cut down. They’ve grown back from these pictures. Every time we paint or something, we have to cut them down. Did the house seem run-down, or were you surprised when you walked in the president’s house?

WAGNER: I didn’t think it was. Well, I knew he was a country man, so I really didn’t have any idea of what I was getting myself into. It was going in there all cold, and no idea of what he lived in or how he lived or what I was going to be doing or any great detail.

WILLIAMS: Were you aware of any maintenance problems that Mrs. Truman put off? Or if something went wrong, would she avoid having people come in? There were some damaged areas, like wallpaper stains, and we’ve been told that she didn’t want the wallpaperers to come in because they would disturb Mr. Truman. Did anything like that ever happen while you were there?

WAGNER: Well, she protected him very closely—really protected him. All I remember is when the furnace would come on, it would moan. You knew there was the ghost, because it really sounded like a [makes moaning sound] Oooh! It was like a big bellow coming out of the basement.

WILLIAMS: Was the house warm enough in the wintertime?

WAGNER: I never had any problem. You know, if there was extra heat, I think there was a space heater in the study that we used very seldom.

WILLIAMS: Did she use the fireplaces at all?

WAGNER: No, we didn’t use the fireplaces at all.

WILLIAMS: I think this was in the wintertime, so the leaves are off of the grapevines.

33

Here’s the carriage house. Were you up there much?

WAGNER: I was never in the carriage house.

WILLIAMS: But that’s where they parked?

WAGNER: Right.

WILLIAMS: And that’s their car. That’s Mrs. Wallace’s.

WAGNER: There used to be a camera right up in here, I believe.

WILLIAMS: I think there’s a box over here pointing one way. They took all that out. . . This is one of the upstairs bedrooms.

WAGNER: Because, see, I was never up in the upstairs rooms.

WILLIAMS: These are kind of mixed-up on the interior, but this is his dressing room upstairs. Did you ever have to go up and get clothing or anything?

WAGNER: They would be handed to me. Because I remember walking up the stairs. There was a room with a lot of . . . Oh, what was it? Linens and material and boxes.

WILLIAMS: That must have been the storage room. This is the upstairs . . . what we call the Truman bedroom. It’s right above the first-floor bedroom.

WAGNER: Now, that’s not open to the public yet, is it?

WILLIAMS: No.

WAGNER: Because that’s for Margaret, if she ever wants to . . .

WILLIAMS: Right. Now, here’s the downstairs bedroom. I think this furniture came along later, according to Margaret. Were there chests of drawers and things in there?

WAGNER: Let me see. God, that one doesn’t look . . . Hmm.

WILLIAMS: I think she bought that particular furniture when her mother was alive.

34

WAGNER: See, I don’t remember this. Yeah, I don’t remember this piece of furniture.

WILLIAMS: Was there something similar?

WAGNER: There was a chair right in the middle here.

WILLIAMS: On the north wall.

WAGNER: And there was a dresser, but I don’t remember where the dresser was. I thought maybe it was over here?

WILLIAMS: On the northeast corner. And I suppose that was the bathroom?

WAGNER: Right, the bathroom went over here.

WILLIAMS: Which one would you use?

WAGNER: I probably used his.

WILLIAMS: You didn’t ever go upstairs to—

WAGNER: No.

WILLIAMS: Or downstairs to the servants’ bathroom?

WAGNER: No.

WILLIAMS: It’s kind of primitive. [chuckling]

WAGNER: I never did that.

WILLIAMS: Here, that’s the way the bedroom looks now. Is that as you remember it?

WAGNER: There was something in the middle.

WILLIAMS: Like a table?

WAGNER: Mm-hmm.

WILLIAMS: Were there end tables and lamps and . . . The same wallpaper?

WAGNER: Yeah.

WILLIAMS: There’s like a recliner here right by the door. Was there a chair? You said you’d sit in the bedroom.

35

WAGNER: Well, we’d have a chair right here if we really wanted to make sure that everything was going all right.

WILLIAMS: Was it just one of the house chairs, or was it—

WAGNER: It was a reclining chair, and he used it a lot too.

WILLIAMS: This is upstairs.

WAGNER: I didn’t even know they had a TV set.

WILLIAMS: They never watched TV, that you knew of?

WAGNER: No. Radio.

WILLIAMS: The attic.

WAGNER: Never was up in the attic.

WILLIAMS: The basement.

WAGNER: Yeah, dirt floors.

WILLIAMS: Is this what the basement . . . ?

WAGNER: Yeah, basically. Yeah. There was one little area, I guess, when you came down, a real narrow place. Is this where you came down the steps, or . . . ?

WILLIAMS: The steps are over here in this—

WAGNER: Okay, then over here, I guess that’s where the meat was cured at.

WILLIAMS: Like it was hanging from the rafters?

WAGNER: Yeah, it was on rope or something like that.

WILLIAMS: Here’s the big furnace.

WAGNER: Is that the new one?

WILLIAMS: It’s the old one. We have a new one now. Here’s a view of looking . . . The steps would be over here on the left.

WAGNER: Okay. I think once or twice I was down in the basement.

36

WILLIAMS: They apparently had extra freezers.

WAGNER: Oh yeah, lots of freezers, lots of food.

WILLIAMS: This is way back in the back; you probably never explored. You recognize the study/library?

WAGNER: Yeah. They had a lot more knickknacks on the shelves. I don’t remember very many knickknacks.

WILLIAMS: You mentioned, before we started, the ivory. Is that something you’re particularly interested in?

WAGNER: Well, there was just so much of it there, and I thought it was very well . . . you know, good taste.

WILLIAMS: Did you ever ask Mrs. Truman about it?

WAGNER: No. It was just kind of just don’t ask too many questions about what’s what. Do your job and enjoy.

WILLIAMS: So you never said like, “I’m fascinated by this painting. Could you tell me about it?”

WAGNER: Oh no, we were just kind of . . . It was hard at times because you could say, “Well, this is a very nice piece,” and she’d say, “Well, thank you.” [chuckling]

WILLIAMS: No story followed, usually?

WAGNER: No.

WILLIAMS: Is this the way the study looked?

WAGNER: No.

WILLIAMS: What’s different?

WAGNER: Oh, my gosh. Let’s see, where’s the window?

37

WILLIAMS: It’s over here on the left. This is taken from the music room doorway.

WAGNER: Okay, there’s a reclining chair over here, right?

WILLIAMS: Mm-hmm. This table was probably pushed back.

WAGNER: Yeah, real close, and this was always full of books.

WILLIAMS: Were these two chairs over here?

WAGNER: No. Let’s see, which chair did we sit in? That was her chair, I think, and I sat—

WILLIAMS: The one on the left?

WAGNER: And this chair was brought over on this side.

WILLIAMS: The kind of rounded chair was over by the music room door?

WAGNER: Mm-hmm.

WILLIAMS: Did you ever know them to play records?

WAGNER: No.

WILLIAMS: There are quite a few records in there. And the telephone was in there?

WAGNER: Yes.

WILLIAMS: Where else were the telephones?

WAGNER: One in the pantry area, and that phone. It’s the only two phones I know about.

WILLIAMS: This is the dining room.

WAGNER: Mm-hmm.

WILLIAMS: That’s upstairs. The dining room. Did the dining room look basically . . .

WAGNER: Yeah, sure did.

WILLIAMS: Were there a lot of plants? Did Mrs. Truman—

WAGNER: No, I don’t remember very many plants. Maybe one. Being a horticulturist

38

now, I don’t remember anything like that.

WILLIAMS: Were you in the kitchen very much?

WAGNER: Oh yeah.

WILLIAMS: This is the pantry back behind the sink. Is that basically what you remember? Lots of stuff. [chuckling]

WAGNER: Yeah, basically. You know, twenty years ago.

WILLIAMS: This is as you enter the front door. Is that—

WAGNER: Yeah, that’s it.

WILLIAMS: Did they talk about Margaret very much, brag on her or anything?

WAGNER: No, just the incident with the newspaper. That was basically it. You know, when she did her singing debut and somebody made some negative comments and . . .

WILLIAMS: You heard that story?

WAGNER: Oh yes, they would speak about that.

WILLIAMS: That’s kind of a nice story to tell here, because this is the way she looked on her debut. This is the dress she wore.

WAGNER: Oh, was it?

WILLIAMS: The hat and coat over there.

WAGNER: Yeah.

WILLIAMS: The music room.

WAGNER: That’s it. What’s this?

WILLIAMS: It’s a potted plant.

WAGNER: Yeah, I don’t think that was there. Yeah, there was a TV downstairs, but it was never on. No, it was just on when the boys were there, the kids.

39

WILLIAMS: Mrs. Truman never watched, that you know of?

WAGNER: To my knowledge, no.

WILLIAMS: The living room.

WAGNER: I don’t know about that table.

WILLIAMS: The table to the left of the gold chair? I think we’ve moved that somewhere.

WAGNER: Yeah, that was jade, wasn’t it?

WILLIAMS: Mm-hmm, on the mantle. Ivory. Here’s some over here.

WAGNER: I don’t remember those lamps, but . . .

WILLIAMS: Two, on the ends of the sofa.

WAGNER: See, most of the time we would probably sit in this chair so we’d have a direct view into the bedroom.

WILLIAMS: The gold chair?

WAGNER: Yeah. Every once in a while we’d sit in that chair, but not very often. We sat in that chair probably waiting for him to . . . you know, if we were called upon.

WILLIAMS: The flowered chair?

WAGNER: Yeah.

WILLIAMS: Would he ever sit out here in the living room?

WAGNER: I think he sat out there like once or twice—very, very few times. I don’t remember those plants.

WILLIAMS: Portraits up here?

WAGNER: Yeah.

WILLIAMS: Bathroom.

40

WAGNER: Yeah.

WILLIAMS: Probably familiar to you. [chuckling]

WAGNER: Mm-hmm.

WILLIAMS: This is upstairs here. Is this the storage room that you were talking about, the room with the linens and . . . up the staircase?

WAGNER: It was like an open room, like an open area upstairs. I don’t know what that was.

WILLIAMS: That’s it.

WAGNER: That’s it, huh?

WILLIAMS: Did you come up the stairway from the kitchen?

WAGNER: No, from the main entrance.

WILLIAMS: Okay, that would be the center hallway. This is back above the kitchen. Now, this is the kitchen.

WAGNER: Mm-hmm. The toaster’s still on the kitchen table.

WILLIAMS: It’s probably a different one, but there’s . . . This is Mrs. Truman’s desk, right at the top of the steps.

WAGNER: I’ve never seen that.

WILLIAMS: Looking from the music room. And the piano.

WAGNER: Oh yeah.

WILLIAMS: Did you ever hear them talk about the Johnsons or the Nixons or . . . ?

WAGNER: No.

WILLIAMS: I guess President Nixon was president then. Were there ever any comments, commentary about that?

WAGNER: Yeah, that was probably it. No, we didn’t discuss very much politics-wise.

41

Might say, “Did you have a nice visit?” That was about it.

WILLIAMS: This is the hallway at the top of the steps in the front of the house. Is that what you were thinking of?

WAGNER: No. I wish we’d have gone upstairs, but . . .

WILLIAMS: The kitchen.

WAGNER: Oh yeah.

WILLIAMS: And this side door is the one you would use most often?

WAGNER: Mm-hmm.

WILLIAMS: What did you think of the colors back here?

WAGNER: Let’s see, those were different colors, weren’t they?

WILLIAMS: Green and red.

WAGNER: God, it’s been so long.

WILLIAMS: I don’t know why these aren’t in color, but they don’t take them that way. More of the music room and living room.

WAGNER: Gee, I don’t remember plants in there at all.

WILLIAMS: The chairs were arranged like this, though?

WAGNER: See, that chair doesn’t look . . .

WILLIAMS: The flowered chair?

WAGNER: I remember this chair quite well.

WILLIAMS: The gold one.

WAGNER: There were no plants in that room.

WILLIAMS: Those must have been later additions then. But things on the tables look similar, and the mantlepiece?

WAGNER: This side looks fine, but this chair doesn’t look right.

42

WILLIAMS: You don’t like where the flowered chair is?

WAGNER: No.

WILLIAMS: Okay, the butler’s pantry, into the kitchen.

WAGNER: There was a phone in there somewhere.

WILLIAMS: I think it’s off on the right.

WAGNER: Yeah, that looks . . .

[End #4377: Begin #4378]

WILLIAMS: Do you remember this fixture in the dining room?

WAGNER: Mm-hmm.

WILLIAMS: Did you ever use it for anything?

WAGNER: Did they set something on there to keep warm or warm up something?

WILLIAMS: It’s over the furnace. There’s a door, and we think it was used way back when for plates to keep warm. Do you remember, or on top?

WAGNER: I thought they put them on top.

WILLIAMS: You mean, at dinnertime or . . . ?

WAGNER: Yeah, dinner plates.

WILLIAMS: Oh, okay. This is the hutch in the dining room, along that wall.

WAGNER: I’ve never seen it open.

WILLIAMS: Cabinet in the dining room.

WAGNER: And more of the pantry.

WILLIAMS: The butler’s pantry here. I don’t think that can of air freshener is in there anymore.

WAGNER: [chuckling] Yeah, there’s a light—

WILLIAMS: What did you think of the house architecturally? Did you have any interest

43

. . . ?

WAGNER: Oh, I thought it was a beautiful house. I really enjoyed it. And it had its boards that creaked, and single-pane glass.

WILLIAMS: Here’s a picture of the study, looking into the music room.

WAGNER: I don’t remember that chair at all.

WILLIAMS: With canes sitting around.

WAGNER: I thought they were all in . . . Well, there was, yeah, canes sitting around, but there was a—

WILLIAMS: There’s quite a few.

WAGNER: In the one location, there was a lot of canes.

WILLIAMS: Would he use one?

WAGNER: He always had one cane.

WILLIAMS: He didn’t change?

WAGNER: With a gold band on it. That was it.

WILLIAMS: This is in the living room. Did you ever use these books?

WAGNER: No, anything that was behind the case we never touched—I never touched.

WILLIAMS: Did you ever hear any story about the portraits?

WAGNER: No. There should be a tusk across here.

WILLIAMS: On the mantle? I wonder if it’s been moved, too. Does the hat and coat rack look similar?

WAGNER: There should be an umbrella on there.

WILLIAMS: I think there is. Is it back there?

WAGNER: Could be. Yeah.

WILLIAMS: But it was kind of cluttered-up like that?

44

WAGNER: Mm-hmm. Well, not that overly cluttered. Maybe one or two jackets on it, but that was the extent of it.

WILLIAMS: Is this the . . .

WAGNER: Oh, there it is. God, that was beautiful stuff.

WILLIAMS: The ivory. Every time you touch it, a little something will tip over or fall. [chuckling]

WAGNER: Oh, I was so scared to touch anything.

WILLIAMS: This is more of the music room. I don’t suppose you played the piano?

WAGNER: I heard the piano being played one time, and I was coming into the house at that time, and as soon as I came in it was stopped.

WILLIAMS: Was it him?

WAGNER: I think it was Margaret.

WILLIAMS: That’s all of the . . . Well, what was it like when he died? Did that mean you were out of a job?

WAGNER: It didn’t even phase me, because I was in the room when it happened. And he knew, I mean, it was happening at that time. And the doctor was there, the nurse was there, and I think there was one other corpsman, because he was getting off duty and I was coming on. And the doctor and the other corpsman didn’t want to take his blood pressure anymore. They were scared. Nobody wanted to do the last of anything. And I can understand it, you know. And then when I told them, I said I couldn’t get a blood pressure, that’s when I went, “Oh, God.” Not “I’m losing a job,” but “He’s dead.” You know, “He’s gone.” And I got very close to him and to the family, because I loved working with her and I loved working with him.

45

You know, like you’re losing your grandparents. That’s what it felt like. And everything happened so fast thereafter, because that’s when the Secret Service took over, heavily took over.

WILLIAMS: Were you whisked out of the scene, or did you stay around for the funeral?

WAGNER: Oh yeah. Well, we were in the room until . . . the remains left, and that’s when the Secret Service just took over. But no, we went to the funeral and all that, got our invites, and we went. That’s when the Army was supposed to escort us, and the individual that was escorting forgot the direct paths to follow the . . . and the corpsmen got stuck way in the background at the funeral home. And that kind of upset me because I wanted to be right up there, but just to be part of it, I guess that was supposed to satisfy me and . . .You know, I just thought that he should have been on time, you know, [chuckling] on time and everything else.

WILLIAMS: Were you amused that the Army was escorting Navy corpsmen?

WAGNER: I guess it didn’t phase me. I knew he was an officer and I guess I had to accept an officer and couldn’t tell him, “You messed up.” I think it was an honor, you know, like everything else was, to be invited to the funeral, and that meant a lot to me. A lot of the corpsmen, after he died, got together right afterwards, but I had no desire to do that. I wanted . . . to be away.

WILLIAMS: What happened after? How much longer were you in the Navy?

WAGNER: Let’s see, I left Independence probably like the middle of January of—

WILLIAMS: A few weeks later?

WAGNER: What was it, a few weeks? It seemed maybe about three, three weeks later, and it was an interesting . . . Well, we were all requested to come over to

46

the Secret Service office, and there was someone at the other end of the line—and I forget who it was—and he wanted to know where we wanted to be transferred to and all this. Well, I didn’t know that we could request . . . I think most of the time you were given three choices, or you’d mark down three choices, and maybe you were given one of those three choices. Or if there was an opening. And they came out and asked you, “Where did you want to go?” And I had no idea. I’m going, “Geez!” And I just thought, Well . . . That summer I took a week’s vacation and went out to California, because I had relatives out there, and I said, “Well, what’s available in L.A. or that area?” And he said, “Well, there’s an opening in Long Beach.” “Oh, okay.” He said, “All right.” So I drove out.

We all left Independence at the same time. Don Nauser went out to San Diego. Was it San Diego or Twenty-Nine Palms? I think it was Twenty-Nine Palms, a Marine base there. And Chuck Rowe, he went back to Chicago. That was his hometown, and that’s where he wanted to go. He was the black sheep, you might say, of the group. He was a radical. He was highly opinionated. Boy, I don’t know where the other two went.

WILLIAMS: Did you stay in the VIP Medical Corps?

WAGNER: No, when I got my transfer, I went to the emergency room at Long Beach and took my duties there, and it was basically like a rotating . . . I was in charge of the emergency room, but I was also to fill in at the clinic. There was a regular clinic there, and I filled in over there and also rotated over to the medical/surgical clinic to assist in those areas. The Navy wanted me to stay in the service, and the doctors and the nurses were really, really

47

pleasant out there. I really enjoyed my tour of duty.

I think I still correspond . . . Well, no, Ruth Spence was my top nurse at Bethesda, and I still correspond with her. She’s living in Florida. The nurses that I met in Long Beach, I wrote letters and there was no forwarding addresses.

It was a nice group of people out there. I enjoyed it. The doctors were really doctors. There was a couple of nurses that were very military-type, but for the most part everybody was pleasant. I think Bethesda was very strict military, but Long Beach was a little bit relaxed, and at one time it all of a sudden got tight, that you did have to wear a uniform. Because a lot of us lived off base, lived across the street in civilian housing, and there for a while we used to go across the street with our work clothes on—just run, you know. [chuckling] And at one point they finally made sure that you had to be dressed in uniform properly going across the street off base. But that was my last duty station.

I wanted to go back to college and went back to the University of Missouri. I was doing animal science and genetics at Ohio State prior to that, and thought this would be a good place, too, because this is where I started meeting friends and all that, living here for two years.

And I went to school, too. There was a campus at one of the high schools, I believe, not too far from there that I took a genetics course and, oh, a math course at. Well, it was during a shift change, and I had to take a walkie-talkie. I’ll never forget the one time that they called me and I was right in the middle of an exam. Well, the instructor I had, I came out and

48

told him that . . . that I’m on private duty. I did not go into any great detail, and I said, “I will have to carry this walkie-talkie with me.” And it went off one day, and I felt like, “Oh, my gosh!” You know, it was just so bad. How do you hide something like that?

WILLIAMS: You said you visited with Mrs. Truman after Mr. Truman died?

WAGNER: Yes.

WILLIAMS: Was that just as you were passing through town, or would you make special trips up here?

WAGNER: Well, I have friends in Kansas City, and she was special and I wanted to visit with her—you know, of course no great length of time, but just to let her know that I still cared.

WILLIAMS: Did she or the house seem different when you visited at all?

WAGNER: Just quieter. There was an emptiness there. And you always kind of felt sorry for her. But, you know, both of them can’t live forever, and you hate to see one live on without the other. But it’s going to happen to all of us. But it was just really difficult, you know. I always wanted to say, “Well, where’s Mr. President at?”

WILLIAMS: Did you talk about him when you visited her?

WAGNER: No. Basically, health care, whatcha doing, and . . . It was proper protocol, I guess, to spend not . . . you know, fifteen minutes was the length of time that you should visit. And once I got permission . . . Well, when I called up Mrs. Truman and said, “I would like to visit with you,” and she would say, “Fine,” I’d say, “Okay.” Then you’d have to call over to the Secret Service—and hopefully some of the officers were still there that knew

49

you—and say who you were, and they’d say, “Fine.” So you always had to check in over there, then go across the street. I had keys, of course, or if I knew the code or something, could get into the house, but I never thought that was necessary. I thought I would always make sure that I’d go over there first and then go across the street. Just got used to it, you might say.

I think it was a real honor . . . My dad and my younger sister were visiting me in Independence, and I got a telephone call—I guess while they were—and Mrs. Truman extended the invite for my dad and sister to visit. And that was quite—

WILLIAMS: That was nice.

WAGNER: Really nice.

WILLIAMS: When did you get the autographed picture?

WAGNER: It was the first year that I was there. The first week, he took one of his memoir books off the shelf and said, “Please spell your name.” And I’m going, “Okay . . .” Then he handed it to me. So that book’s been awful special. And at that time I thought, “Oh, this is really great.” Then Mrs. Truman, a couple days later, said, “You know, that was his personal book.” I went, “Whoa!” [chuckling] So that book will always be here.

WILLIAMS: Is this what they looked like when you were there?

WAGNER: Yeah. Oh yes.

WILLIAMS: Is this something?

WAGNER: Well, that was just my orders at that time.

WILLIAMS: If you can make sense of it, I can’t. [chuckling]

WAGNER: Well, see, this is the way I received it, but when you . . .

50

WILLIAMS: You don’t have to take it out.

WAGNER: No problem.

WILLIAMS: I guess if you’re in the military you understand what all that . . .

WAGNER: Well, yeah.

WILLIAMS: Oh, I see.

WAGNER: This is basically when I arrived in Kansas City. I guess, what’s his name? Beale was the captain there of the Naval Reserve. And this was the orders that I had to mark down. Every time I stopped overnight, I had to mark something down.

WILLIAMS: That sounds familiar. We have to do that on this trip. [chuckling]

WAGNER: Well, it’s typical.

[End #4378; Begin #4379]

WAGNER: It’s typical of government work.

WILLIAMS: When you got there, when you leave.

WAGNER: You make sure you’ve got every receipt. And then notes from Mrs. Truman were basically a typed letter. These are letters . . .

WILLIAMS: And some birthday . . .

WAGNER: Some birthday cards. And a Christmas gift. I gave them a Christmas gift, and they gave one back to me, which was a surprise. I got a tie from them.

WILLIAMS: A tie?

WAGNER: Mm-hmm.

WILLIAMS: Scott has become an expert on neckties. He’s catalogued hundreds of them recently.

WAGNER: Well, let’s see, this one . . . I thought I received a pair of cufflinks from

51

them. Mrs. Truman gave each of the corpsmen a set of their personal cufflinks. And that was a real big surprise. We all went in the house when we got our orders and were leaving. We all set up a time and she invited us in. That was real hard because it was shortly after the death, and we talked, and she wanted to know where you were going. She said, “Well, this is a little token of our appreciation,” a set of cufflinks and . . . [voice choking with emotion] And this is another tie.

[Conversation between Williams and Stone ensues regarding tapes and terminating the interview—not transcribed

WAGNER: These are just the president’s.

WILLIAMS: Oh, they’re presidential cufflinks.

WAGNER: Well, but I got a pair of his personal ones, also.

WILLIAMS: When did you get these?

WAGNER: Just before I left. This was the last letter I got. This was in ’76. This is when I last heard from Bess.

WILLIAMS: It’s an engraved card that says, “I deeply appreciate your holiday greetings and send you my best wishes for the new year,” and it’s signed “Bess Truman.” These cufflinks say “Richard Nixon” on them.

WAGNER: It must have been the time when he came to visit.

WILLIAMS: The Trumans didn’t cherish these? [chuckling] They gave you . . .

WAGNER: No, I mean, that was given to us . . .

WILLIAMS: Oh, when he was there?

WAGNER: When he was there.

WILLIAMS: I see. I thought maybe they handed them down to you. [chuckling]

52

WAGNER: No.

WILLIAMS: We’ve heard that they weren’t real fond of the Nixons.

WAGNER: No. Well . . .

[inaudible chitchat—not transcribed]

WILLIAMS: So, after 1976, you didn’t have any more correspondence?

WAGNER: Right. Let me check on this. Those are his cufflinks. Yeah, those are his cufflinks.

WILLIAMS: So those were just a pair of his that she gave you?

WAGNER: Mm-hmm, his personal . . .

WILLIAMS: Kind of gold . . . I don’t know what you’d call the pattern here. Do you use them? [chuckling]

WAGNER: No. No.

WILLIAMS: I don’t have much call for cufflinks.

WAGNER: Pardon?

WILLIAMS: I don’t have much call for cufflinks, but if the president gave me some, I’m sure I’d keep them around.

WAGNER: Well, yeah, just like these. I had a . . . when we were asked to pick our duty stations, they asked me if I would go down to Johnson. Well, as soon as we left, I think it was two days later, he died.

WILLIAMS: Right.

WAGNER: I went, “Wow!” But I was informed that it wouldn’t be . . . I probably wouldn’t have liked it down there because he was a little bit . . .

WILLIAMS: Remote? Different?

WAGNER: Quite different.

53

WILLIAMS: A Texan. So you have clippings.

WAGNER: Oh yeah, I did all this.

WILLIAMS: A thank-you card for a birthday greeting.

WAGNER: Let’s see, this was Christmas Eve.

WILLIAMS: December 20, 1971. So, people know you as Bill.

WAGNER: Mm-hmm.

WILLIAMS: Did the press ever try to contact you for a lowdown on his condition?

WAGNER: Yeah. One did.

WILLIAMS: What did you say?

WAGNER: I had no comment. [chuckling] Matter of fact, there was somebody about two years ago that was writing a book on Truman—I have no idea what his name was—and he wanted the lowdown on his health and, you know, this and that. And I came out and told him, I said, “You know, I don’t reveal . . . .” He said, “Well, you’re not in the military anymore. There’s no reason . . .” So I told him, “I took a code of ethics back then, and I still believe in it.” And he got kind of nasty, and I said, “Well, I think this conversation should just end.”

WILLIAMS: I didn’t cross the line, did I?

WAGNER: No, you didn’t ask any of the . . .

WILLIAMS: There’s a part of me that wants to know everything you can.

WAGNER: Well, yeah.

WILLIAMS: The historian part of me, but then there’s the part that says it’s none of my business.

WAGNER: Matter of fact, after I got out of the service and went back to Mizzou, or

54

went to Mizzou, I joined the MVA, Missouri Veterans’ Association, and one of the kids was a journalist and we became friends. Then, all of a sudden, my roommate at that time, because I lived in a trailer, moved out and I had a room. And he said, “Well, would you mind?” “No, that’s great.” You know, “got to split fees around here.” Why would I keep a two-bedroom trailer for myself? So he moved in . . . well, I guess it was for one full year. And by the end of the first . . . They’re on semesters, right?

WILLIAMS: Mm-hmm.

WAGNER: He was trying to get nosy, and I said, “I really don’t discuss this.” And it got kind of heated, and he said, “Well, that was one of my reasons to move in, to find out . . .” I said, “Well, then, you lost out, guy.”

SCOTT STONE: He had an ulterior motive.

WAGNER: I’ll bet you’ve got all these books. [sound of pages turning] Let’s see, that’s ’73.

WILLIAMS: From Mrs. Truman?

WAGNER: Yeah.

WILLIAMS: July. What would she—

WAGNER: Oh, that I got accepted at the University of Missouri.

WILLIAMS: [reading] “It was indeed thoughtful of you to write me as you did, and I appreciate it.” That was nice.

WAGNER: And then, let’s see, that was in California also. This is May.

WILLIAMS: Of ’73?

WAGNER: Mm-hmm.

WILLIAMS: When you visited her, did she seem relieved, in a sense? Like when you

55

have a spouse that’s ill and then they die, is there kind of . . .

WAGNER: Oh boy, she kept things to herself so much.

WILLIAMS: You didn’t sense anything, though?

WAGNER: There was like once or twice during his illness she kind of . . . But she really kind of kept everything inside of herself. [sound of pages turning] I don’t think there’s anything else in this one.

WILLIAMS: Had you ever been to a big military funeral like that?

WAGNER: No. My gosh, there were so many people there. It was after it was in the newspaper who was going to the funeral, they put the listing out. You know, 90 percent of the people didn’t know what I was doing, and they see my name down there. And it was, “No, that must be another Bill Wagner. Oh, that has to be another Bill Wagner.” And before I left, I told them. I said, “Yes, I was the one.” But I just . . . we were asked not to say yes or what we were doing.

WILLIAMS: Did you get the big, long telegram from the Army?

WAGNER: Yeah, it’s in here somewhere.

WILLIAMS: We saw one of those earlier this year, about three or four or five pages.

WAGNER: Yeah.

WILLIAMS: Telling you if you accept, call this . . .

WAGNER: It was kind of ironic. The adjutant general that wrote it is a friend of mine now, Colonel Crisp, Bill Crisp. Let’s see, these are letters from senators and all that. I’ve got matches.

WILLIAMS: Harry S. Truman matches. Do we have any of these?

STONE: I haven’t see any. We could probably find some. [chuckling]

56

WILLIAMS: I think there may be some down there in the living room with all the cards and bridge stuff.

STONE: Very likely.

WAGNER: And this was the . . . Yeah, you had to present one of these when you went into the funeral. All the coded bars on it. Did you see these?

WILLIAMS: No. What did three bars mean, do you know?

WAGNER: Well, each one meant a different . . . You were invited to a different area. See, this one had—

WILLIAMS: This was the best?

WAGNER: Well, this was for everyone. This is the state funeral service. This was at the library. Which one was that for?

WILLIAMS: Truman Library.

WAGNER: Okay, that was just probably to get to a certain area. This is the telegram. Ever seen one of those?

STONE: That looks like the same one.

WILLIAMS: Yeah, that’s the same, a big long . . .

WAGNER: Yeah.

WILLIAMS: Fifth United States Army. Did you think you would be invited to the funeral? Did you really know?

WAGNER: I didn’t know that we were . . . I thought we were just going to be kind of . . . off we go. We each got one of those.

WILLIAMS: So he did tell you that there shouldn’t be a period after the S?

WAGNER: Mm-hmm. He said, “It’s just an S.”

WILLIAMS: That’s a point of dispute.

57

WAGNER: Oh, he came out and said that so many times. Because, see, when I spoke to him in the evenings and then when you read his memoirs, it was just like, “Wow, he’s saying this!” And it was just amazing. There was so much history.

Even when I was at Bethesda Naval Hospital, there was so much history there also, a lot of the admirals and generals. Admiral Frank Jack Fletcher. I don’t know if you ever heard of that name. You know, he was in charge of the Pacific Fleet, I believe, at that time. Well, he was a patient there. And he was neat, a neat old man. He was still, “Sailor!” [chuckling] You’d go, “Whoa!” And his grand-niece—it was a niece or a nephew—lived in Independence, and I got invited for dinner over there one night. And I was so scared because, you know, they knew the whole connection. Because Mrs. Fletcher was still alive, and Mrs. Fletcher found out that I got transferred, and she called them up and said, “You get him over for . . .” [chuckling] Oh, that was a . . . And God, there were so many of them up there. When you get old books out, you know, World War II books, and, “My gosh!” and they were there, you know, I took care of them.

And Frank Jack was really a neat guy. There was one comment he always said that, “I’ve got to pump ship.” [whispering] “You’ve got to pump ship? Hey, what’s going on here?” Well, that was to urinate. I never, you know . . .

STONE: In Navy talk. [chuckling]

WAGNER: Yeah, pump ship. And he was really nice. And there was a lot of good ones there, congressmen and senators.

58

STONE: Well, that’s where they send all the presidents anymore, so . . .

WAGNER: Pardon?

STONE: That’s where they send all the presidents now.

WAGNER: Yeah, well, just before I got transferred, there was eight of us . . . like four corpsmen and four nurses that got selected . . .

[End #4379; Begin #4380]