Last updated: January 8, 2025

Article

"The Old Flag Never Touched the Ground:" Sergeant William H. Carney Jr. Story Map

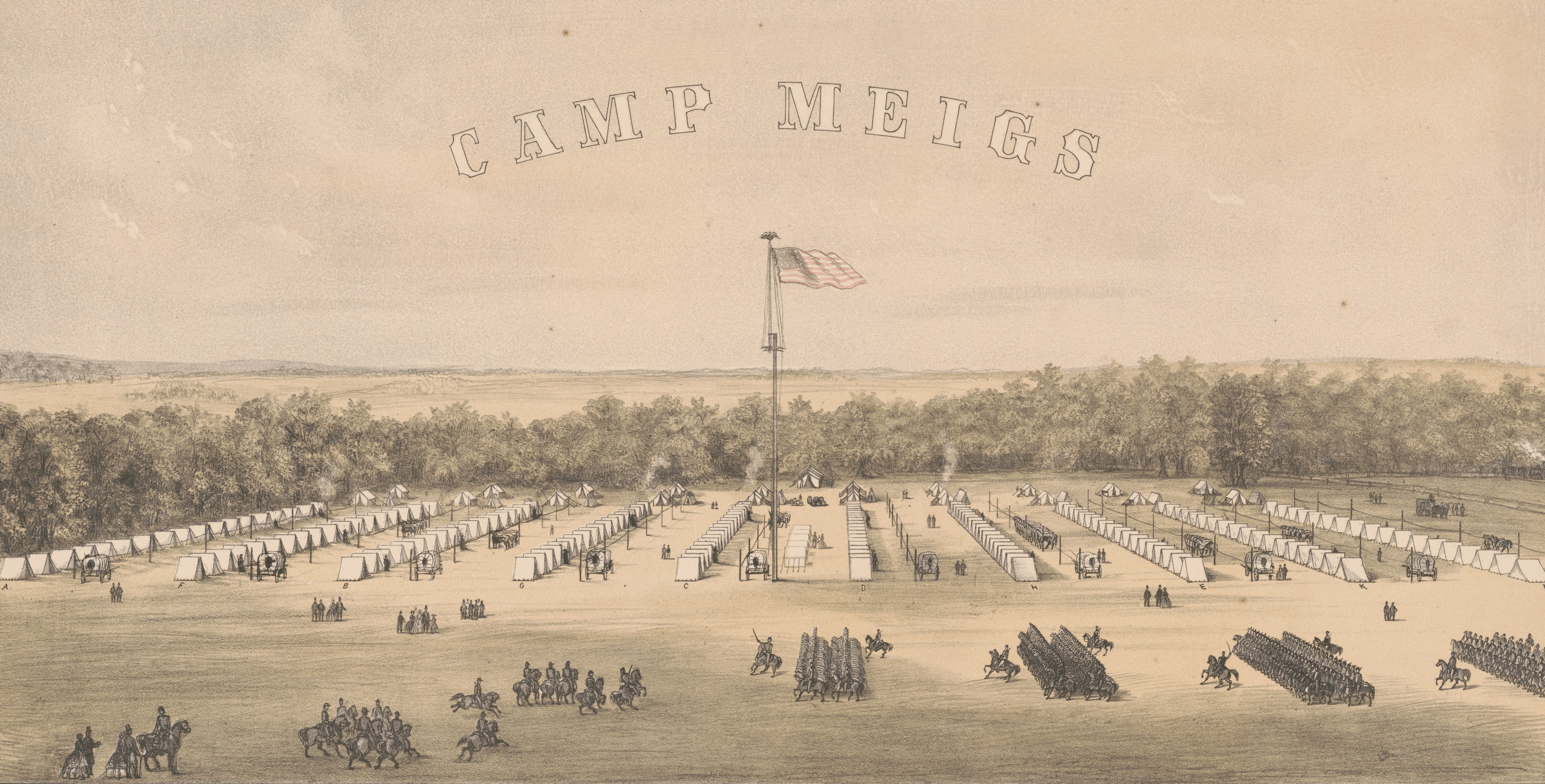

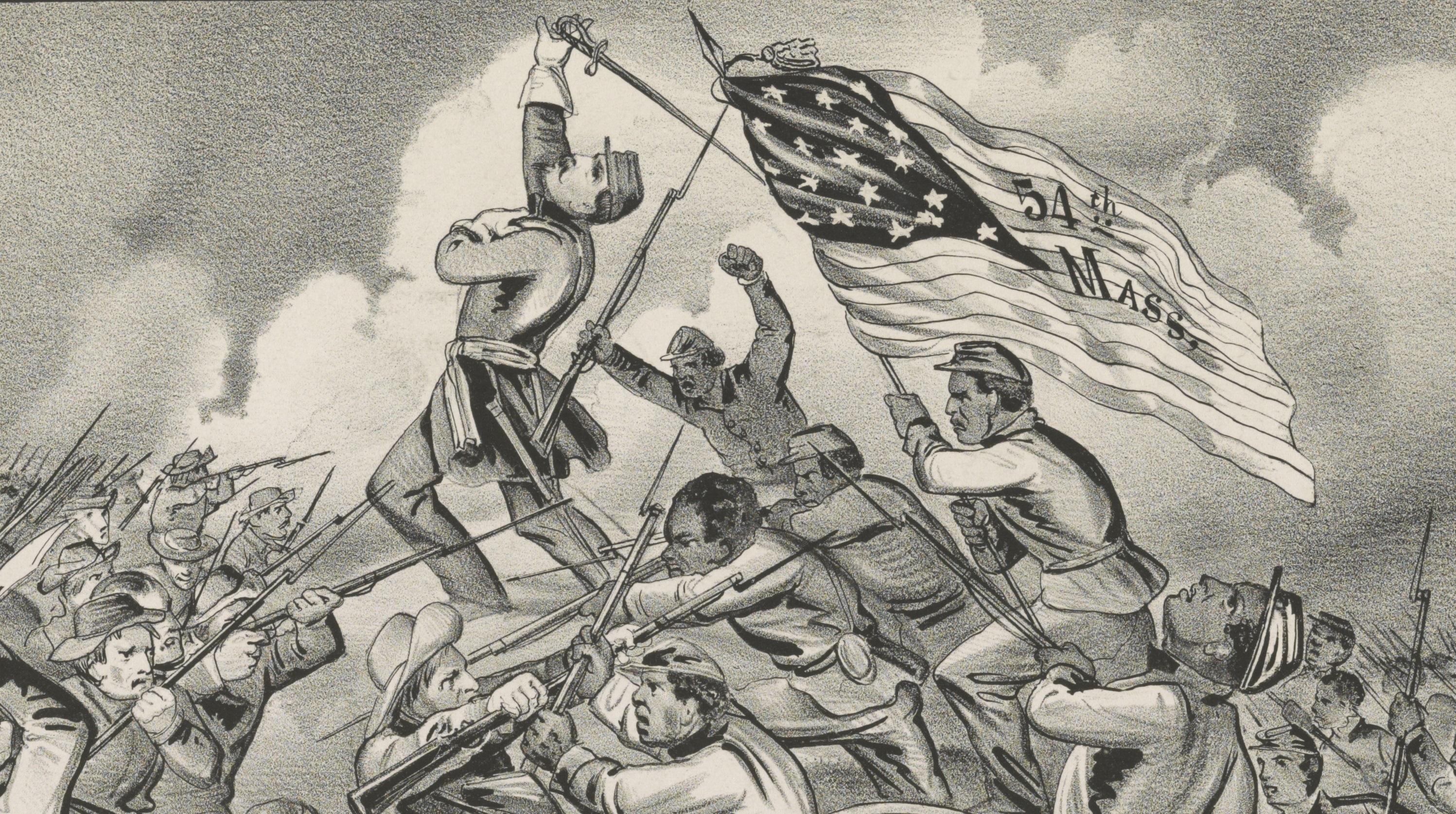

When President Abraham Lincoln called for the raising of African American regiments during the US Civil War, Black men from around the country traveled to Boston to enlist with the 54th Massachusetts Volunteer Regiment. This story map highlights the experiences of Sergeant William H. Carney Jr., one of the men who joined this historic regiment and continued to serve his community throughout his life. To explore additional stories, visit A Brave Black Regiment: The 54th Massachusetts.

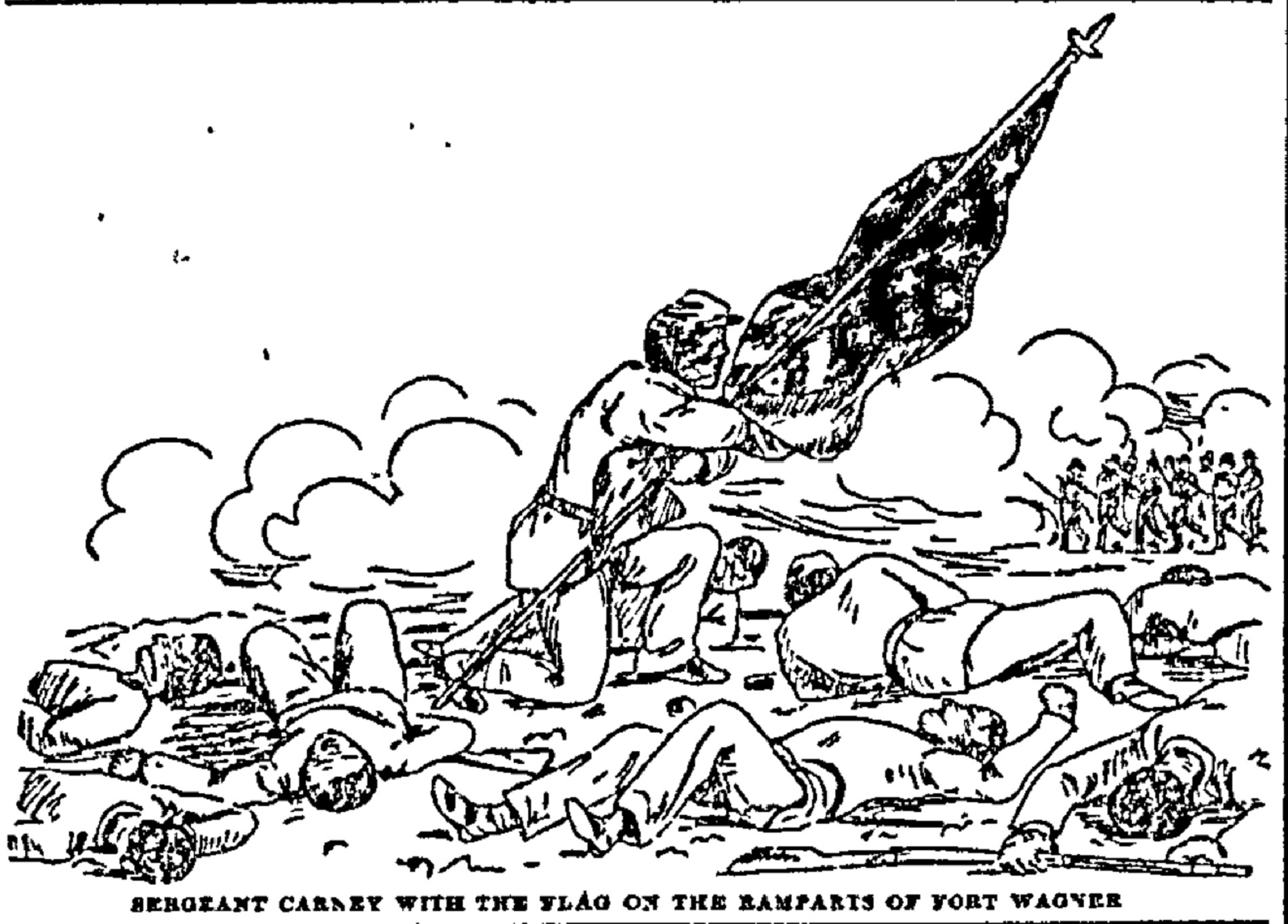

Following his escape from slavery in the 1850s, William H. Carney Jr. began his new life in New Bedford, Massachusetts. Heeding President Lincoln's call for Black soldiers in 1863, he joined the 54th Massachusetts Volunteer Regiment, one of the first Black fighting units in the Civil War. During the 54th's gallant assault on Fort Wagner, South Carolina, Carney saved the regiment's flag. For his actions, Carney became the first African American recipient of the Medal of Honor. Respected around the nation, he dedicated the rest of his life to family, community, and public service.

Explore the story map below to learn about Sergeant William H. Carney Jr.'s service during the Civil War and his contributions to his community after the war. Click "Get Started" to enter the map. To read more about each point, click "More" or scroll to view the map, historical images, and accompanying text. To navigate between the points, please use the "Next Stop" button at the bottom of the slides or the arrows on either side of the main image. To view a larger version of the main image depicted below the map, click on the image.

Footnotes:

[1] Liberator. November 6, 1863.

[2] William Still. The Underground Railroad. Medford, New Jersey: Plexus Publishing, 2005. P.315-316.

[3] Kathryn Grover. The Fugitive’s Gibraltar: Escaping Slaves and Abolitionism in New Bedford, Massachusetts. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2001. P. 253-4.

[4] Liberator. November 6, 1863.

[5] Kathryn Grover. The Fugitive’s Gibraltar: Escaping Slaves and Abolitionism in New Bedford, Massachusetts. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2001. P. 253-4.

[6] Liberator. November 6, 1863.

[7] Boston Herald, March 5, 1863, “Military.”

[8] Louis Emilio. A Brave Black Regiment. A History of the Fifty-fourth regiment of Massachusetts volunteer infantry. Boston Book Company 1891. P 9-10 https://archive.org/details/historyoffiftyfo00emil/page/n59/mode/2up?q=Morgan+Guards

[9] Boston Semi-weekly Advertiser, March 25, 1863.

[10] Matthew J. Clavin, Toussaint Louverture and the American Civil War: The Promise of Peril and a Second Haitian Revolution, (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2011), 125-126.

[11] Company Descriptive Book, Fold3 https://www.fold3.com/image/260466950 pg 3.

[12] Carl Cruz. “Sergeant WillIam H. Carney.” It Wasn’t In Her Lifetime But It Was Handed Down: Four Black Oral Histories of Massachusetts. Office of the Massachusetts Secretary of State. UMASS Amherst. 1989. https://archive.org/stream/itwasntinherlife00wach/itwasntinherlife00wach_djvu.txt

[13] “The 54th Before Fort Wagner,” New Bedford Evening Standard, July 28 1863, pg 2.

[14] “Letter From the 54th Regiment,” New Bedford Evening Standard, July 28 1863, pg 2.

[15] “Bravest Colored Soldier,” Boston Herald, January 10 1898, p 6.

[16] “Correspondence,” New York Tribune, Tuesday, Aug. 4, 1863

[17] New Bedford Evening Standard, May 4 1864, p. 2 “A medal of honor has been awarded to Sergt. William H. Carney, of this city, company C, 54th Mass. Regiment, for gallant and meritorious conduct in the Morris Island campaign.” According to Carney’s descendant, Carl Cruz, “the first medal he was given was the Gilmore Medal of Meritorious Award which was basically given right on site...He was also awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor. The tragic end of the story was that he got it late and did not have a formal ceremony. He received the medal in 1900. It was awarded to him in 1863. He did not receive it because there was an oversight in the papers. There was a gentleman by the name of Christian Fleetwood who also fought in the 54th and was putting together the 1900 Exhibition in Paris that was going to show Blacks. He asked Carney for his medal and some other documents. They later found out that he did not get the medal. So Mr. Fleetwood petitioned the War Department along with Luis Fenollosa Emilio, who wrote A Brave Black Regiment: A History of the 54th Regiment of Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry, 1863-1865. So along with sending in those documents, the medal was sent to him with the acknowledgment.” (It Wasn’t In Her Lifetime But It Was Handed Down: Four Black Oral Histories of Massachusetts) According to the The Colored American June 2 1900, “In connection with the Negro exhibit at the Paris Exposition, Mr. Thomas J. Calloway conceived the idea of making a collection of photographs of colored men who had received medals of honor from the Congress of the United States...It was during this search that the gentleman in charge found to his great surprise that no medal from Congress had been issued to Sergt. Carney, and after corresponding with the gallant sergeant, took up the case personally, searched for and found the necessary evidence to establish the claim, put it in proper form, and submitted to the Secretary of War for action. It is needless to say that the action was favorable, and now at all subsequent encampments, re-unions and other official functions, the bronze star with its broad striped ribbon will be conspicuous on the broad chest of the brave hero Sergt. William H. Carney.” Military records show that Carney finally received the Medal of Honor in 1900, “Medal of Honor awarded May 9, 1900, for most distinguished gallantry in action at Fort Wagner, South Carolina, July 18, 1863” (Fold3 https://www.fold3.com/image/260466997 pg 17).

[18] “Bravest Colored Soldier,” Boston Herald, January 10 1898, p 6.

[19] New Bedford Evening Standard. December 12 1863, pg.2.

[20] Carrie Lee Blanchet. “William Harvey Carney.” Negro History Bulletin. February, 1944. Vol. 7, No. 5. Pp 107-108. Published by Association from the Study of African American Life and History and “Marriages Registered in the City of New Bedford for the Year eighteen hundred and sixy-five.”

[21] New Bedford Evening Transcript. January 2 1866, 2

[22] Carl Cruz.

[23] New Bedford Evening Transcript. July 5 1865, p. 2

[24] “Lecture To-Morrow Evening” The Brooklyn Union, April 17, 1867

[25] New Bedford Evening Transcript. July 13, 1869.

[26] Carl Cruz.

[27] Earliest Known African American Figures in Postal History | National Postal Museum

[28] Blanchet.

[29] Blanchet.

[30] David Blight. Race and Reunion: The Civil War in American Memory. Cambridge: Belknap Press of Harvard University, 2001. P 195

[31] Boston Daily Advertiser, December 25 1871 p.2

[32] Boston Traveler, September 4 1872, pg 2

[33] Boston Herald, July 28 1887, Boston Evening Transcript, August 2 1887, Boston Globe, August 2, 1897.

[34] Boston Herald, March 6, 1891 and Boston Herald, April 4 1903. Boston Herald, June 6 1895 p.6. Boston Herald, September 22 1897, p.9. Boston Herald, June 7, 1901, p. 5. Boston Herald, April 20 1903. Boston Herald, April 20 1903. Boston Herald, May 29 1904, p. 31, and May 31, 1904, p.3. Boston Herald May 29 1904, p. 31, and May 31, 1904, p.3. Boston Herald, August 18, 1904, p. 3. Boston Journal, July 10 1897.

[35] The Shaw Memorial: A Celebration of an American Masterpiece. Eastern National. 2002. Pg. 39.

[36] Booker T. Washington. Up From Slavery: An Autobiography. New York: A.L. Burt Company, 1901. P. 253.

[37] “Fought with the 54th," Boston Herald, October 1, 1901.

[38] Blanchet.

[39] Boston City Directory, 1902, p. 294 1902, Boston directory - Boston Directory, 1789 to 1901 - (bostonathenaeum.org) and Boston City Directory, 1904. Page 352. 1904, Boston directory - Boston Directory, 1789 to 1901 - (bostonathenaeum.org)

[40] Boston Herald, November 24, 1908, p.12, “All accounts of the accident are substantially the same...Sergt. Carney, thinking a passenger was to leave the car, stepped back. An instant later he stepped forward, but the elevator man, thinking he had moved away purposely to await the return of the car downward, started again. The upward movement of the car and the forward movement of Mr. Carney were simultaneous, and almost at the same moment the messenger cried:” Don’t! Stop the car.” His cry was followed by the crushing of his leg and he toppled forward into the car. He had been caught by the ankle between the floor and the sill of the car.”

[41] The Boston Globe, November 23, 1908.

[42] Boston Herald, December 10, 1908, pg 1

[43] Boston Globe, December 10 1908

[44] The Boston Globe, December 12, 1908

[45] Blanchet.

[46] Blanchet.