Last updated: May 13, 2025

Article

Tourism and Wildlife Impacts in Glacier Bay

NPS Photo

How does tourist visitation to the shorelines of Glacier Bay affect wildlife presence and activity?

Principal Researchers:

Mira Sytsma (University of Washington), Tania Lewis (NPS), Laura Prugh (University of Washington)

Dates:

Fieldwork was conducted May—September 2017-2018

Introduction

Shoreline tourism has been growing in Glacier Bay National Park largely due to increased shoreline use by tour vessel passengers. The shorelines of Glacier Bay provide denning locations, foraging habitats and nesting habitat for wildlife and see the highest concentration of human use, therefore increasing the frequency of human-wildlife interactions. These interactions can cause wildlife to alter their activity patterns, and can ultimately impact their survival and reproduction, demonstrating the need for quantitatively understanding how increased human use of the shoreline is impacting the capacity of wildlife and humans to coexist.The goal of this study is to provide information to inform park management of the impacts to wildlife occurring across differing levels of human use to establish biologically relevant thresholds of human use to ensure that significant resource degradation does not take place.

Methods

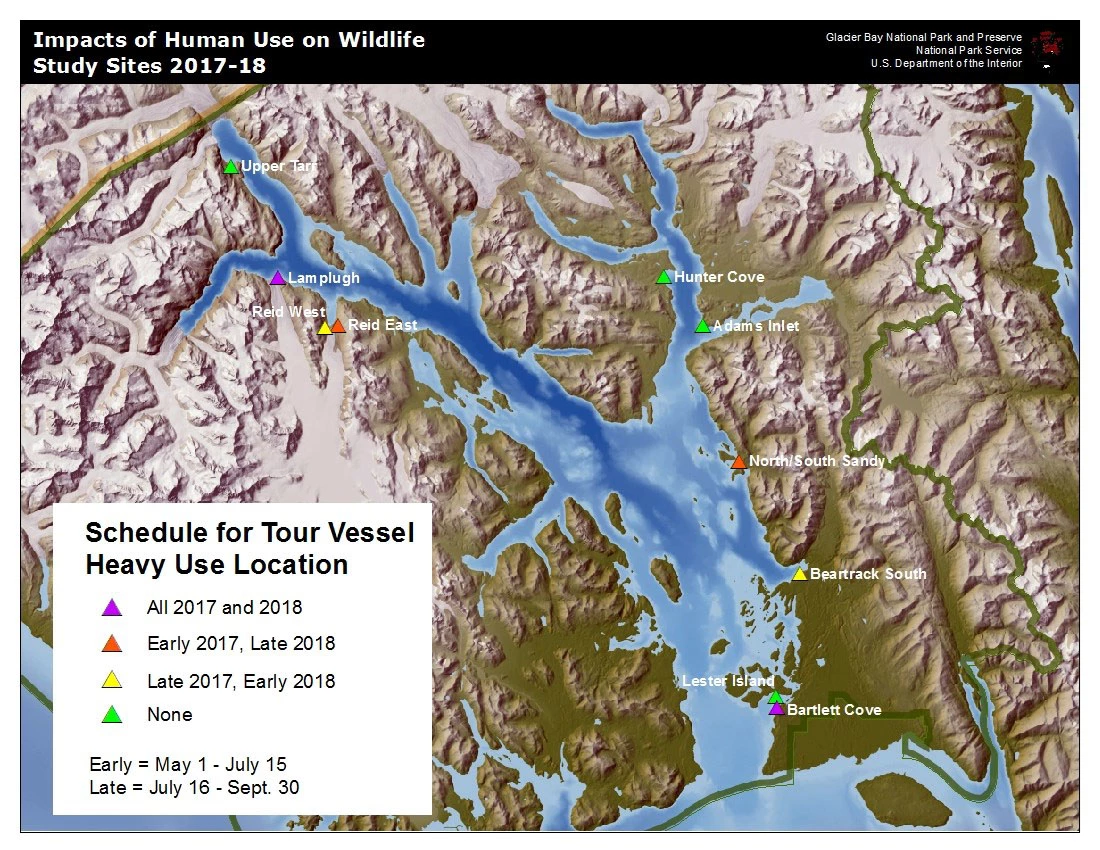

We used remote cameras to quantify presence and activity levels of black bears, brown bears, moose and wolves to understand how their behavior changes in response to human visitation. We placed 4 motion-sensor cameras at each of ten designated study sites throughout the park approximately 0.5 km away from one another.The experimental design of this study involved comparing wildlife activity in areas of human-use with areas of low or no human use. Sites were grouped into pairs and applied treatment of higher human activity by designating and rotating tour vessel heavy use locations (see map). This human activity treatment was included as a categorical variable (high versus low) in statistical analyses.

NPS Photo

Results

We obtained 183,012 photos of humans and wildlife, including 154,444 photos of humans (84% taken at Bartlett Cove), 5,860 photos of brown bears, 3,452 photos of black bears, 6,927 photos of moose, and 570 photos of wolves. Independent detections of each species per camera ranged from 0-8 per week. Human activity ranged from 0-180 camera minutes per week.

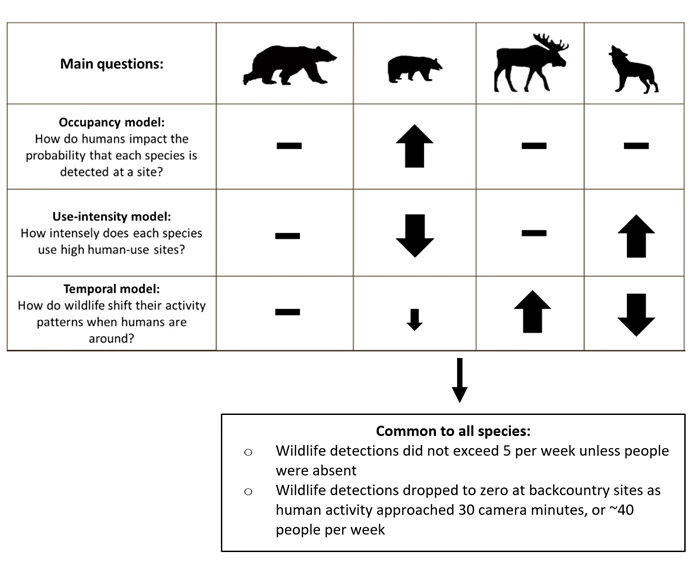

Detections did not exceed five per week for any species unless human activity was absent (zero photos of humans were taken). However, spatial and temporal patterns of wildlife activity in relation to human activity were nuanced and species specific.

- Brown bears were unaffected spatially or temporal by human activity.

- Black bears were more likely to be detected in areas of human activity but used those areas less intensely, and when humans were around, black bears shifted their activity patterns slightly to avoid when people were most active.

- Moose were no more likely to be detected in areas of high human-use versus low human-use and didn’t use either of those areas more intensely than the other. However, when humans were around, moose shifted their activity patterns to align with when people were most active.

- Wolves were no more likely to be detected in areas of high human-use versus low human-use, however, they used areas of higher human-use more intensely. Wolves also strongly avoided humans temporally dropping their activity to nearly zero during midday when humans were most active.

Detections of wildlife dropped to zero at all backcountry sites as human activity approached 30 camera minutes corresponding to ~40 people per week based on a correlation between human camera minutes and number of people per week from camper and tour vessel reports. In Bartlett Cove, detections continued for black bears, brown bears and moose after this threshold was reached but wolves were not detected.

NPS Photo

Management Implications

We found that low levels of human activity can alter wildlife behavior, therefore some combination of spatial and more granular temporal zoning may be necessary to promote human-wildlife coexistence in protected areas. This is a challenging task, and in Glacier Bay it means balancing the contrasting temporal responses of moose versus black bears and wolves with the fact that all species demonstrated some level of spatial avoidance of humans. Further complicating the situation is a growing population of people who seek to visit wild places and view wildlife without displacing the very animals they hope to watch.

- One solution is to continue to utilize the water-based wildlife viewing that occurs in Glacier Bay. Allowing people to view wildlife from a vessel, rather than on land, would allow wildlife to more freely use their space while providing people with a memorable wilderness experience.

- Another potential solution is to use threshold metrics to determine which management strategy—or combination of strategies—to use and where. And while we detected species-specific responses to humans in Glacier Bay, it would be difficult to manage a protected area for each species individually. Instead, management can focus on what species have in common.

- Our results indicate that a threshold level of human activity corresponding to 40 visitors per week potentially displaced all four wildlife species. Land sharing management techniques (or “business as usual” in Glacier Bay) may adequately mitigate human disturbance to wildlife up to that threshold. In areas of Glacier Bay where visitation commonly exceed 40 people per week, land sparing strategies, perhaps in combination with temporal zoning, may be necessary to promote coexistence. Tour vessels have the capacity to take large numbers of visitors to shoreline areas so concentrating off-vessel activities in specific areas while prohibiting use in others may accomplish this objective.