Last updated: October 30, 2020

Article

Why We Laugh

National Park Service

Good friends and casual visitors often remarked about James Garfield’s passion for books and their contents. A visitor to the Congressman’s home on I Street in Washington, D.C.:

“The books… overflowed the library. And undoubtedly the overflow has been regular, as you can go nowhere in the general’s home without coming face to face with books. They confront you in the hall when you enter, in the parlor and the sitting room, in the dining-room and even in the bath-room, where documents and speeches are corded up like firewood.” (quoted in Leech & Brown, The Garfield Orbit, p.182-183)

Garfield’s life-long friend Burke Hinsdale described his reading habits:

“In his later years, he read everywhere—on the cars, in the omnibus, and after retiring at night. If he was leaving Washington for a few days, and had nothing requiring immediate attention on hand, he would go to the great Library of Congress and say to the librarian, ‘Mr. Spofford, give me something that I don’t know anything about.’ A stray book coming to him in this way would often lead to a special study of the subject.” (quoted in TC Smith, James Abram Garfield, Life and Letters, p. 747)

And in the spring of 1881:

Visitors noticed that the White House now seemed filled with books: “Everywhere—in every nook and corner,” a reporter wrote. “A case in the parlor contains editions of Waverly [sic—referring to the Waverly novels by Sir Walter Scott.] and Dickens,” along with “French history in the original, old English poets and dramatists richly bound in black and gold” in the hallways and dining room. (Kenneth D. Ackerman, Dark Horse, p. 322)

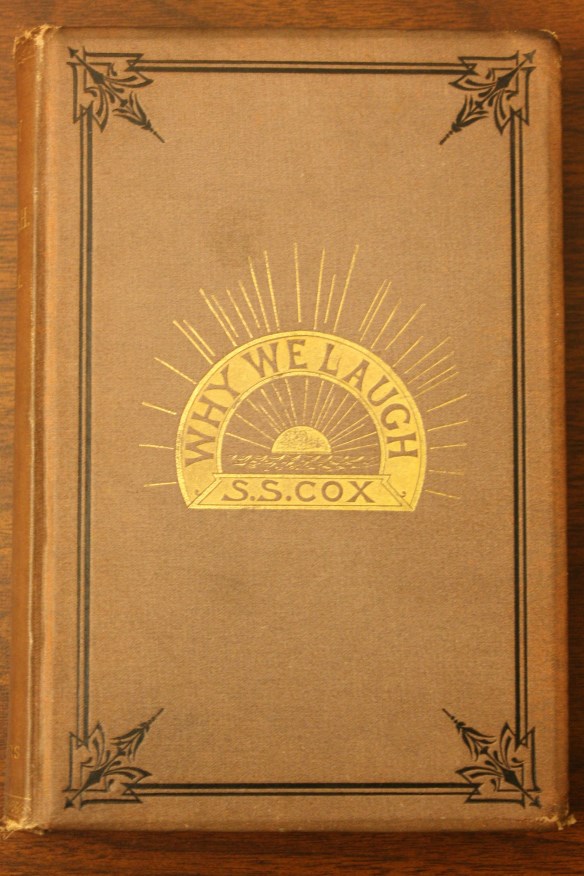

Now, all those books (except, we hope, for the ones borrowed from the “Congressional Library” as Garfield called it) fill the shelves of the President’s home in Mentor, Ohio. The Waverly novels are in the parlor, Dickens is in the boys’ room. About half of the books are in the Memorial Library—an eclectic collection that includes law, religion and philosophy, political history and biography, poetry, and interesting titles like Hygiene of the Brain, Mizpah, and Natural Laws of Husbandry. On a low shelf in a corner hides Why We Laugh, by S. S. Cox.

National Archives and Records Administration

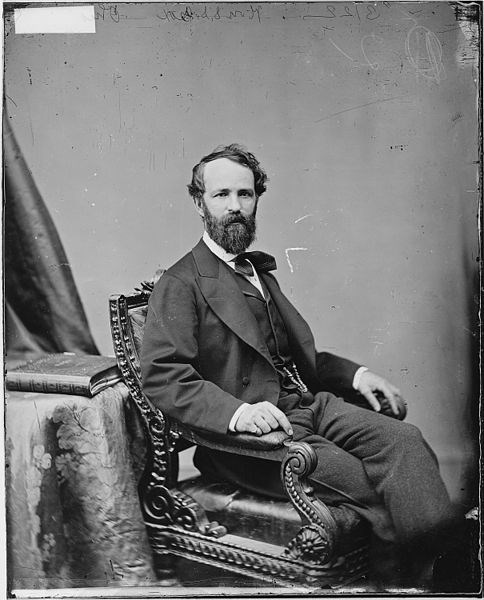

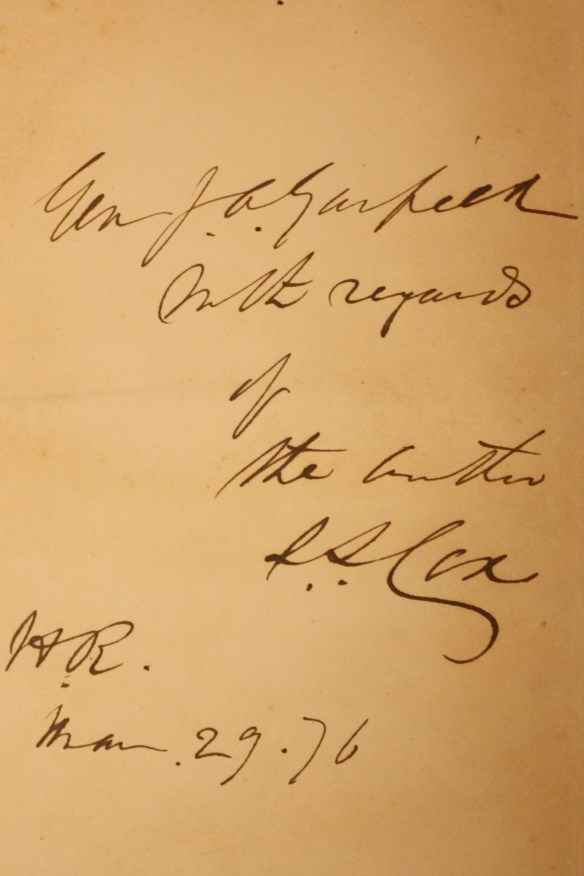

Samuel S. Cox was born in Zanesville, Ohio, in 1824; practiced law in Cincinnati; edited the Ohio Statesman in Columbus; and served as a Democratic Member of Congress from the Columbus area for four terms, from 1857 to 1865. Outspokenly opposed to the Civil War, and to President Lincoln, Cox’s political fortunes in Ohio waned, and he moved to New York. Democrats in New York elected him to Congress in 1868, and he served there until 1883. So, Cox served alongside James Garfield in the House of Representatives for fourteen years. On March 29, 1876, Mr. Cox presented Gen. J.A. Garfield with a copy of Why We Laugh.

Perhaps to impress his readers with his scholarship, Cox begins his book with a classical definition of humor. “Humor, in its literal meaning, is moisture. Its derived sense is different; but while it is now a less sluggish element than moisture, we still associate with humor some of its old relations. In old times, physicians reckoned several kinds of moisture in the human body—phlegm, blood, choler, and melancholy. They found one vein particularly made for a laugh to run in, the blood of which, being stirred, the man laughed, even if he felt like crying…” It quickly becomes apparent that the “We” in Cox’s title refers to Americans in general and legislators in particular.

National Park Service

He asserts repeatedly that American humor is based most often on exaggeration. “The Declaration of Independence is a splendid exaggeration…’all men are created equal’…’all government derives its powers from the consent of the governed’…With such a chart[er], and with such a grand initial momentum, need we wonder at the magnitude of our ideas, the magniloquence of our orators, and the exaggerations of our humor? Our large lakes, our long rivers, our mountain ranges, our mammoth conifers, our vast mineral treasures, our wide prairies, our great crops, our growing cities, our enlarging territory, our unrivaled telegraphs, our extensive railroads and their equally extensive disasters, our mechanical skill and its infinite production, our unexampled civil unpleasantness and its results, would seem to call for an aggrandized view of our political and social position, and, as a consequence, for a broad, big, Brobdingnagian humor.”

Eighteen of Cox’s twenty-five chapters are about legislative humor. Filled with quotes, quips and epigrams, it is quite apparent that Cox found his colleagues to be his most important source of material; this volume is a classic study in the fine Washington art of name dropping. Garfield’s name only appears a few times, most notably in the chapter called Legislative Retort and Repartee: “ It was a railroad grant. ‘Where is all this to lead?’ exclaimed Washburne. ‘To the Pacific coast,’ said Garfield. ‘To the bottom of the treasury rather,’ was the prompt rejoinder.” It doesn’t seem to me that Garfield was an active participant in the repartee. I wonder if every man named between the covers of Why We Laugh received a signed copy.

Were Cox and Garfield friends? In his diary Garfield mentions a number of dinners with other members of Congress, including S. S. Cox. And he notes, “Some of the best men socially in Congress are political adversaries.” But the journals also indicate that in the work of Congress, Garfield found amusement in different places than Cox.

Tuesday, March 5, 1872: On the Judicial Fund a brisk debate sprung up, which drifted off into questions of Ku Klux, in which an amusing passage at arms occurred between Cox of N.Y. and Rainey, a colored member from South Carolina. Cox got the worst of it.

Wednesday, February 9, 1876: In the House the debate continued on the Diplomatic Appropriations Bill and nothing was accomplished. Springer if Illinois and Cox of N.Y. attempted to make fun of the Diplomatic Service and got off a good deal of stale wit, with a little that was bright.

National Park Service

Monday, November 19, 1877: The day was spent on the Paris Exposition Bill. Cox made a carefully prepared speech devoted to witticisms, pleasant to hear but very uncomfortable for the man who indulges in it. I do not believe it is possible for such a man to have a pleasant reputation for good judgment.

This last is after Garfield accepted Cox’s book. Had he read it? Does this entry reflect Garfield’s reaction to Cox’s thesis, or is it more a comment on their political differences?

House colleagues and social friends, Cox and Garfield seem to have had very different senses of humor. Toward the end of his book, Mr. Cox finally explains why he feels levity is so important to legislating:

“Our enjoyments in this life should antedate our future bliss. We have enough clouds of sorrow here. Let us fringe their dark edges with sunshine. Let us mellow and brighten them for the solace of others, if not for the joy of our own heart. Grief and melancholy are selfish. All nature calls for hilarity…In that province of human activity in which life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness are the ostensible objects of guarantee—the province of statesmanship—where the collisions of prejudice, interest, and passion are in constant debate, while there may be no need for the cap and bells of the fool or the acrobatic entertainment of the harlequin and clown, there is ever an urgency for those gifts which cheer, brighten, and bless, and which suffuse through society their soft radiance like the sweet, hallowing influences of sunset.”

Perhaps Mr. Garfield could agree with that.

Written by Joan Kapsch, Park Guide, James A. Garfield National Historic Site, December 2013 for the Garfield Observer.