Last updated: November 2, 2020

Article

Why No Middle Names?

According to Ancestry.com, no one on the Mayflower had a middle name. Nor did most of the Founding Fathers. For centuries in Europe, a legal name consisted of a given or first name and a surname (or patronymic).

While middle names began appearing in the late Medieval times, they were reserved only for nobility in England with an old law making them illegal for the rest of the population. Since the Pilgrims and many early settlers came from England, early American tradition included just the two names. Only about five percent of Americans born during the Revolutionary War era had middle names.

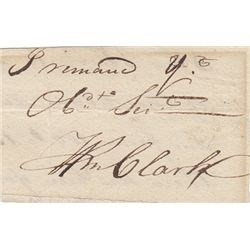

Middle names began to find favor among wealthy extended families in the late 1700s. Aristocratic families increasingly began giving their children two names, so that by the time of the Revolution a quite small but traceable number of southerners carried middle names, mainly those from upper-class families.

In less than a single century middle names were transformed from a somewhat faddish rarity to a practical requirement. The practice began to catch on with the middle class after the turn of the 19th century, and it had become nearly customary by the time of the Civil War. By 1900 nearly every child born had a middle name. In fact, the enlistment form used in World War I was the first government form to provide space to write a middle name – a reflection of the assumption that nearly every person had one.