Last updated: October 23, 2022

Article

Making a Plan: Why Fredericksburg?

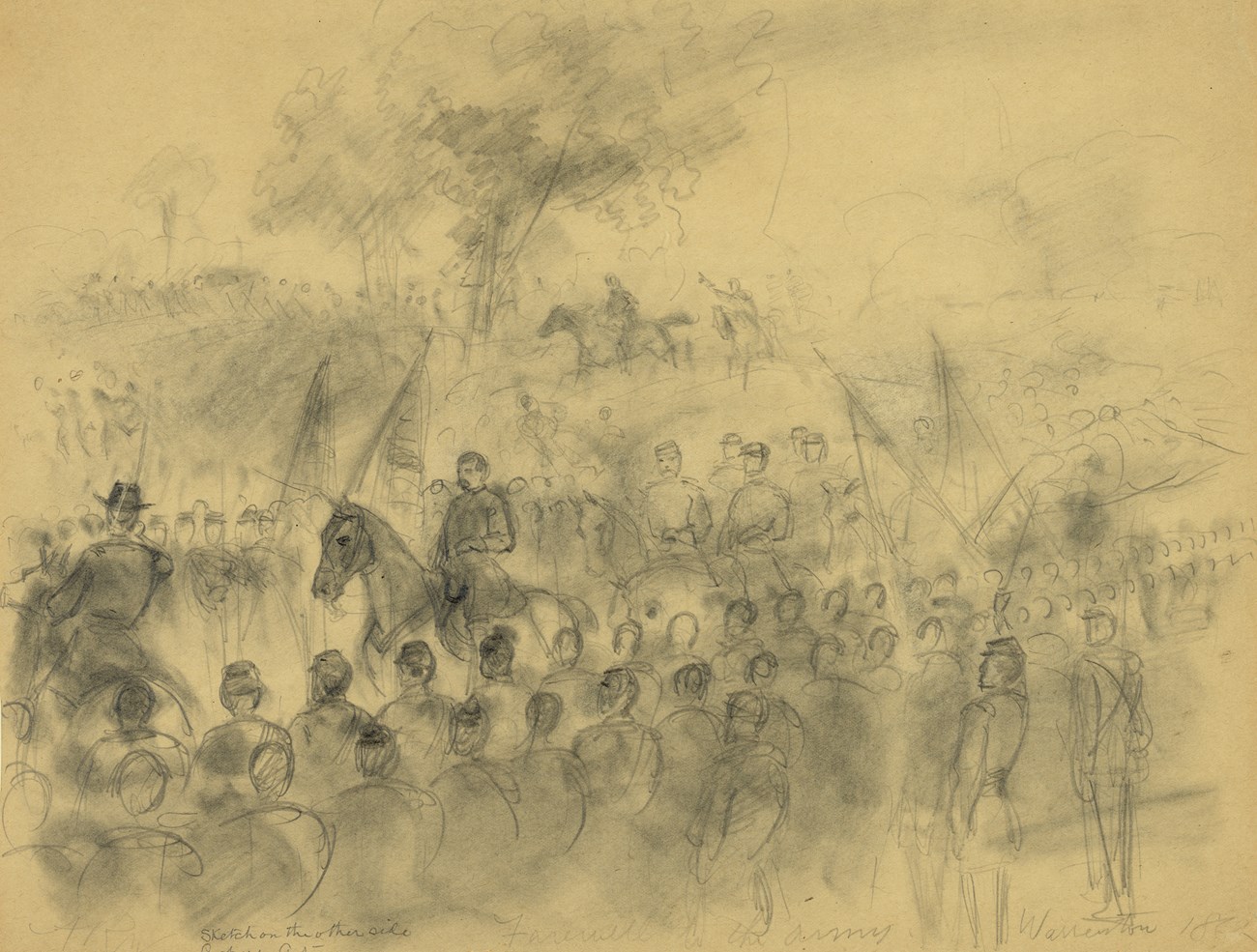

Sketch by Alfred Waud, Library of Congress

On November 10, 1862, George B. McClellan said goodbye to the Army of the Potomac for the last time. Newly promoted General Ambrose Burnside’s training wheels were about to come off.

Three days prior word had arrived from Washington, DC, appointing Burnside command of the army and relieving McClellan. Over those three days, McClellan worked closely with Burnside. McClellan updated the new commander on the status of the Army of the Potomac and answered any questions Burnside had. McClellan keyed Burnside in on a campaign he had been formulating that would allow the Army of the Potomac to have the upper hand. Notably, that meant moving to Fredericksburg.

After Antietam, the competing armies were at a standoff. The United States’ Army of the Potomac was around Warrenton and the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia was closer to Culpeper and Orange. Lincoln demanded military action in the wake of his announcement of the Emancipation Proclamation.

The Army of the Potomac’s current location at Warrenton stretched supply lines dangerously thin. If the army were to move to Fredericksburg, however, its closer proximity to Washington would make supplying the troops easier and had the bonus benefit of placing the troops along a straight path to the Confederate capital at Richmond. McClellan initially wanted to attack near Culpeper and then swing towards Fredericksburg, but in the few days consulting with Burnside after the change of command this plan shifted. The army would move directly to Fredericksburg from Warrenton.

Library of Congress

There were challenges to the Fredericksburg movement, especially the question of how the army would get across the Rappahannock River. Regardless, Burnside was confident. Burnside telegraphed his idea of moving to Fredericksburg to both Lincoln and General-in-Chief Henry Halleck.

McClellan reviewed the Army of the Potomac one last time on November 10. Some soldiers cheered the general who led them for almost a year and a half; others cried. McClellan and his staff boarded a train and left the army on November 11.

On November 14, Halleck sent Burnside a response:

“The President has just assented to your plan. He thinks it will succeed if you move rapidly; otherwise not.”

By the time Burnside got this approval, McClellan was gone. Ready or not, the Army of the Potomac was now Ambrose Burnside’s responsibility. Roughly forty miles to the southeast of Warrenton, the city of Fredericksburg was about to become the focus of an intense struggle. It was there that Burnside would succeed or fail.