Last updated: August 30, 2024

Article

When the Rust Settles

by Johnna Rizzo and Matthew Twombly

Transcript and Image Description

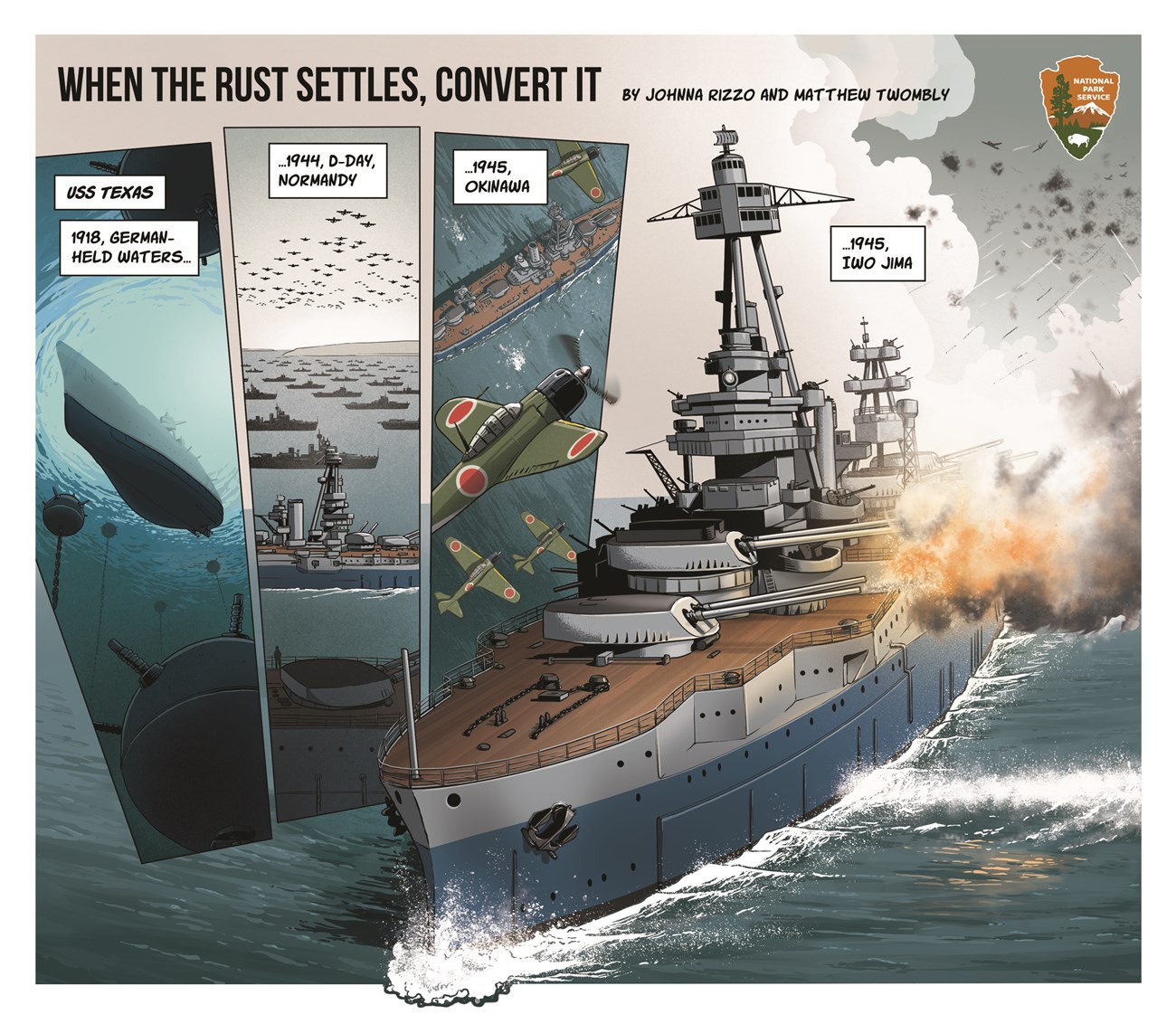

Line 1: USS Texas. Timeline - 1918, German held waters.

Image description: Looking through and underwater minefield at the hull of a ship.

1944, D-Day, Normandy.

Image description: hundreds of aircraft fly over a armada of hundreds of ships

1945, Okinawa.

Image description: Four Japanese aircraft fly a battleship.

1945, Iwo Jima.

Image description: Battleship firing its deck guns

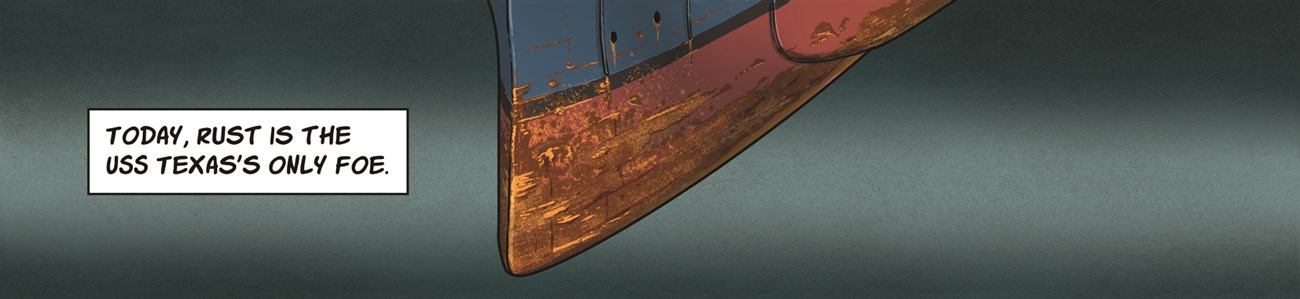

Line 2: Today, rust is the only USS Texas’s only foe.

Image description: Rust forming on the bow portion of a ship’s hull.

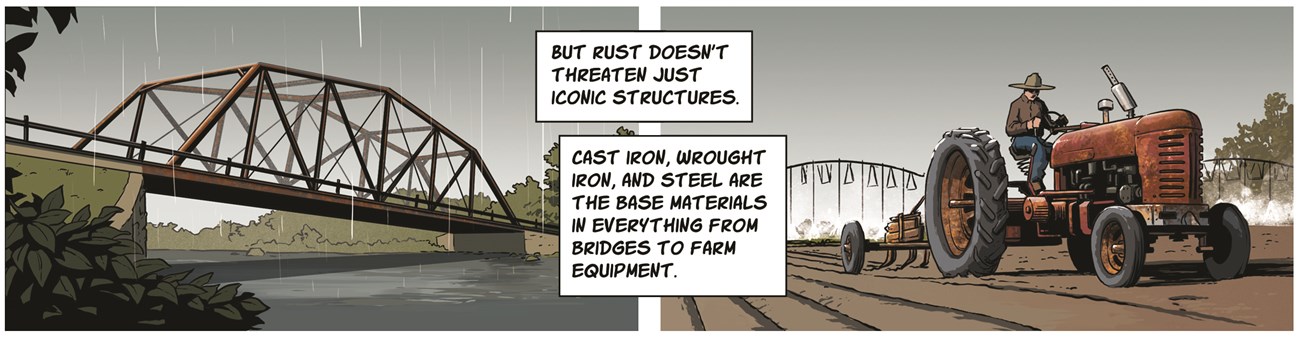

Line 3: But rust doesn’t threaten just iconic structures. Cast iron, wrought iron, and steel are the base materials in everything from bridges to farm equipment.

Left image description: Rust forming on a truss bridge over a river.

Right image description: Farmer plowing a field using a rusty tractor.

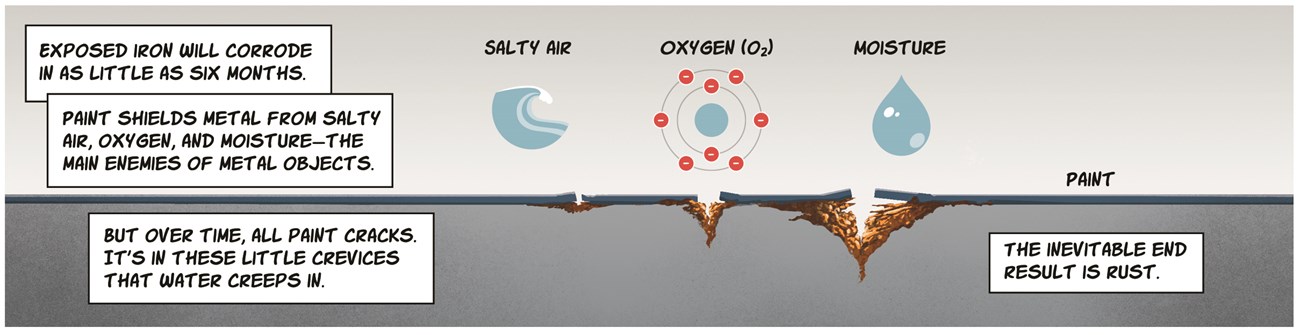

Line 4: Exposed iron will corrode in as little as six months. Paint shields metal from salty air, oxygen, and moisture – the main enemies of metal objects. But over time, all paint cracks. It’s in these little crevices that water creeps in. The inevitable result is rust.

Image description: A line of paint with the different size cracks allowing rust to form.

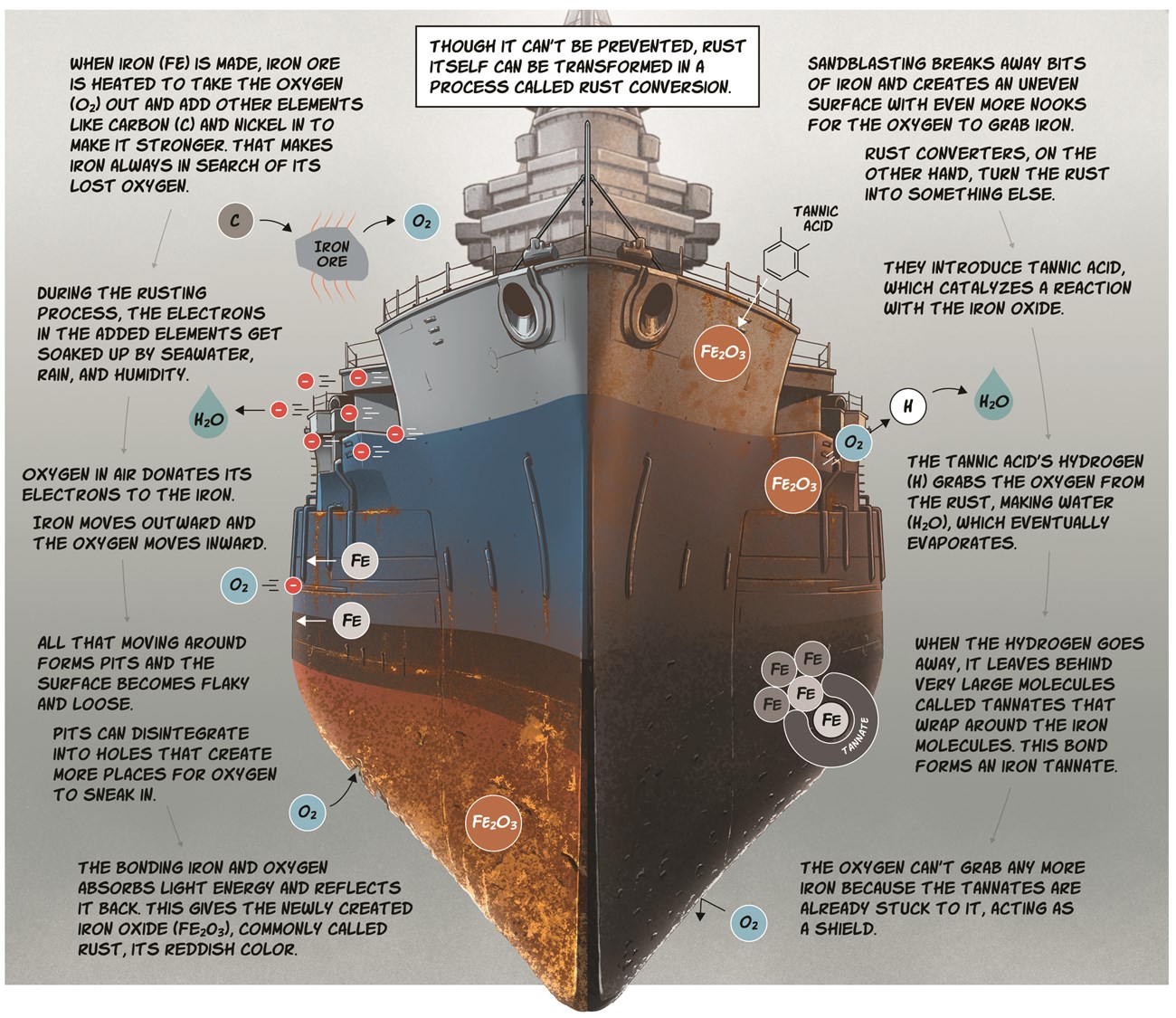

Line 5 text center: Though it can’t be prevented, rust itself can be transformed in a process called rust conversion.

Text left side of the image:

When iron (Fe) is made, iron ore is heated to take the oxygen (O2) out and add other elements like carbon (C) and nickel in to make it stronger. That makes iron always in search of its lost oxygen.

During the rusting process, the electrons in the added elements get soaked up by seawater, raw, and humidity.

Oxygen in air donates its electrons to the iron. Iron moves outward and the oxygen moves inward.

All that moving around forms pits and the surface becomes flaky and loose.

Pits can disintegrate into holes that create more places for oxygen to sneak in. The bonding iron and oxygen absorbs light energy and reflects it back.This gives the newly created iron oxide (Fe2O3), commonly called rust, its reddish color.

Text right side of image:

Sandblasting breaks away bits of iron and creates an uneven surface with even more nooks for the oxygen to grab iron.

Rust converters, on the other hand, turn the rust into something else.

They introduce tannic acid, which catalyzes a reaction with the iron oxide.

The tannic acid’s hydrogen (H) grabs the oxygen from the rust, making water (H2O), which eventually evaporates.

When the hydrogen goes away, it leaves behind very large molecules called tannates that wrap around the iron molecules. This bond forms an iron tannate.

The oxygen can’t grab any more iron because the tannates are already stuck to it, acting as a shield.

Image description: Looking at the bow of a battleship with various amounts of rust on different part of the ship.

Line 6: Rust conversion creates a stable surface that can be painted, saving the iron for another day.

Image description: Silhouette of a battleship on the ocean at twilight.

Source: National Center for Preservation Technology and Training, National Park Service.