Last updated: August 8, 2023

Article

Revolutionary War Pension Files: Tips and a Guide for the Curious

Revolutionary War Pension Project

The National Park Service and the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) are collaborating on a special project to transcribe the pension records of more than 80,000 of America’s first veterans and their widows. The project will make a permanent contribution to the historical record for the 250th anniversary of the American Revolution.

About the Records

The digitized records in the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) online catalog are the result of scanning 2,670 microfilm reels of the Case Files of Pension and Bounty-Land Warrant Applications based on Revolutionary War service, ca.1800 - ca.1912.

The microfilm was created in the 1970s by photographing more than 2.3 million documents in more than 83,000 files. Each file is associated with a surviving Revolutionary War soldier, his widow, or children, who applied for a pension based on the veteran’s service during War for Independence (1775-1783).

The files contain papers that can span over 150 years, from original Revolutionary War documents to 20th century letters from descendants enquiring about an ancestors' service.

Most files have about 30-40 pages of records, but some files have more than 100 or even 200 pages. This may be because a veteran was rejected under the requirements of one pension act, then reapplied and was approved years later under a different act. Or because the veteran was required to make multiple amended testimonies to clarify his service. It may be because a file contains both a soldier’s application and his widow’s, along with witness and supporting documents.

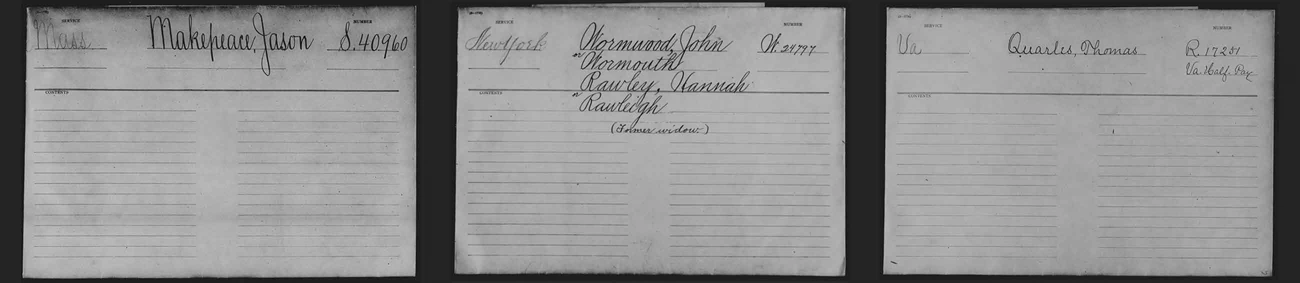

Decoding Pension Numbers

Pension files begin with a reference card listing the veteran’s name, the state where they claimed service during the Revolutionary War, and a pension number. Here’s how to decode the pension numbers.

- S: Pension numbers that begin with “S” are for a “Survivor”—a soldier who applied for and was granted a pension for his service.

- W: Pension numbers that begin with “W” are for a pension granted to a widow. Her name will be included on the reference card. A widow pension may or may not include the veteran’s pension, so it’s important to look through all the documents in the file.

- R: Pension numbers that begin with “R” are rejected pension applications. This doesn’t mean that the entire file was rejected; it only means that the most recent application was rejected. It might show that a soldier applied for a pension under the Act of 1832 and was approved, however his widow, who applied for her own pension years later—perhaps while living in a place far from where her husband served, where there were no surviving witnesses or corroborating paperwork—was rejected.

National Archives and Records Administration

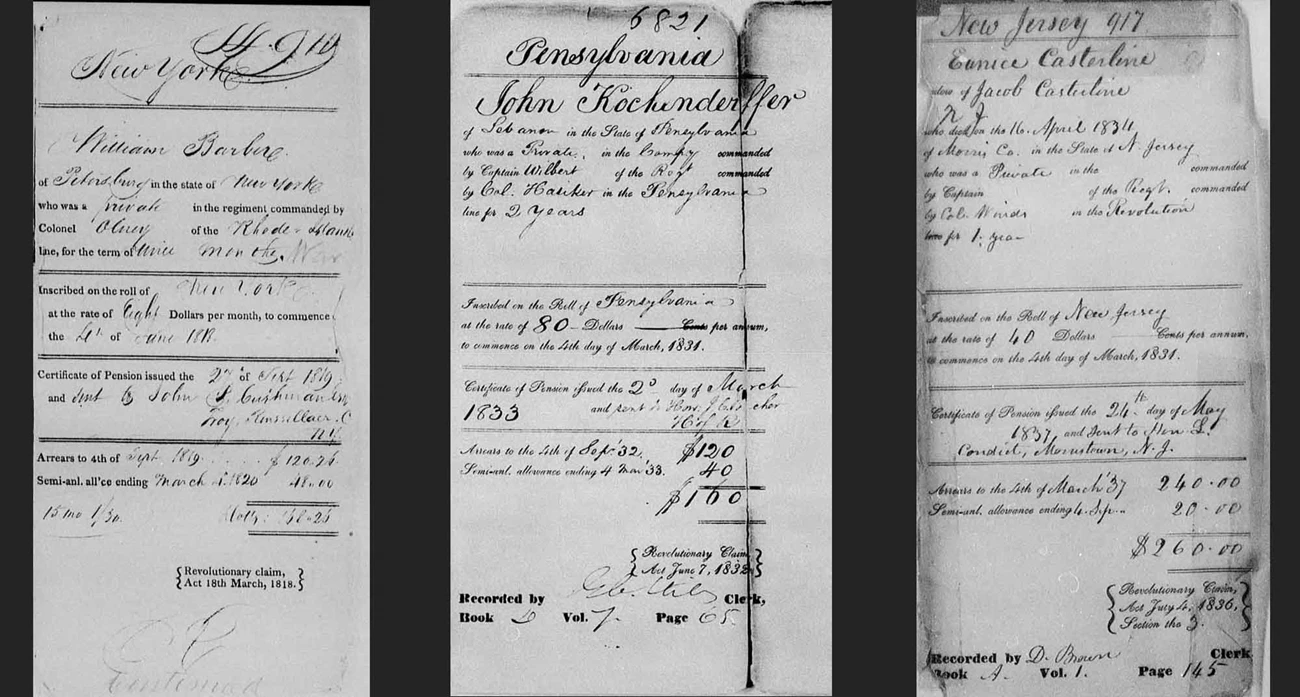

File Jacket Information

Approved pensions include a file jacket that contained the original application paperwork. It summarizes the veteran’s service and lists the amount the veteran or widow would receive. Payments included an initial lump sum owed the pensioner and the annual pension paid out twice a year, in March and September.

National Archives and Records Administration

Tip: Papers within a pension file are not arranged in any particular order

The most interesting or important documents may not be the ones that appear first in a file. Click through and read other documents, particularly those towards the end of the file. That’s where there are some of the most interesting finds.

National Archives and Records Administration

Pension Application Forms

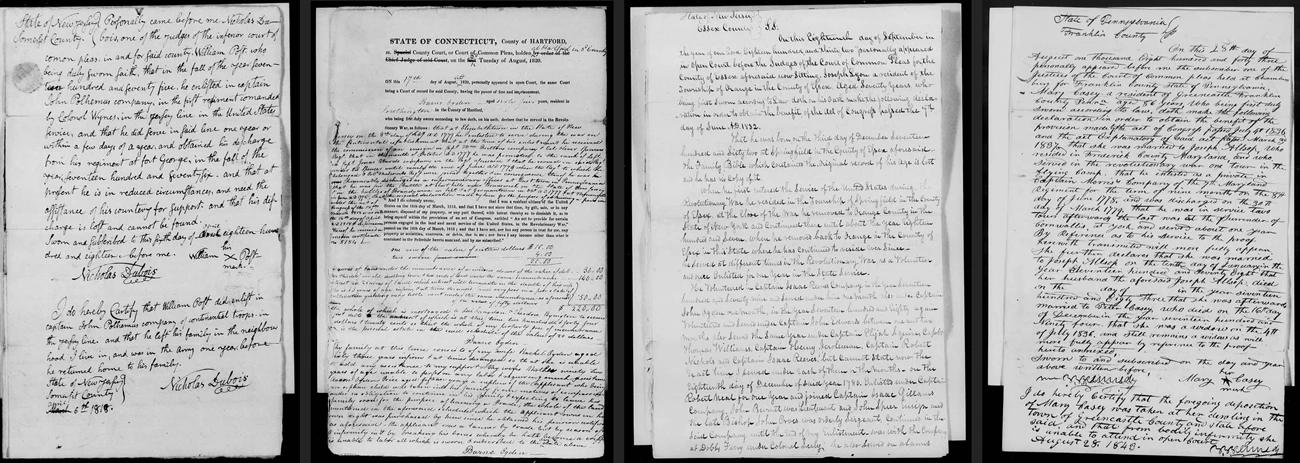

The heart of the Revolutionary War Pension Files are the pension applications. Most applications are handwritten manuscripts, but some applications under the Pension Act of 1820 use printed forms. The forms vary slightly from county to county, and state to state.

The Four Pension Acts - The Differences and Why They Matter

Applications across all four Pension Acts generally start the same way. An introductory statement indicating the state and county where the claimant is giving their testimony, the date of the petitioner’s appearance before the Court or lawyer, the claimant’s name, age, and place of residence.

Pension applications submitted under the first two Pension Acts, in 1818 and 1820 are generally short, averaging just a paragraph or two.

1818 – US Continental Line soldiers eligible for pensions

Since only regular soldiers of the Continental Line (the US Army) were eligible for pensions under this Act, it was fairly easy to check surviving muster and pay rolls to verify whether a person claiming service had served. Long oral narratives weren’t necessary to prove service so are rare under this act. Most applications are the veteran simply naming their company, regimental officers, and the state where they served.

William Post - William Post (NJ) submitted a straightforward pension under the 1818 Act. (Image below.)

1820 – Continental Line soldiers eligible; requires proof of financial need

Pensions granted under the Act of 1820 were still limited to regular army soldiers of the Continental Line, so the information about the veteran’s wartime service did not differ much from applications made under the Act of 1818.

Significantly, the Act of 1820 had an additional requirement for the veteran to prove that he and his family (if he had one) were in dire financial need by providing an inventory of all the property he owned and descriptions of the state of health of everyone in the veteran’s household. As a result, these records track valuable information about families, daily life, society, and public health in the new nation.

National Archives and Records Administration

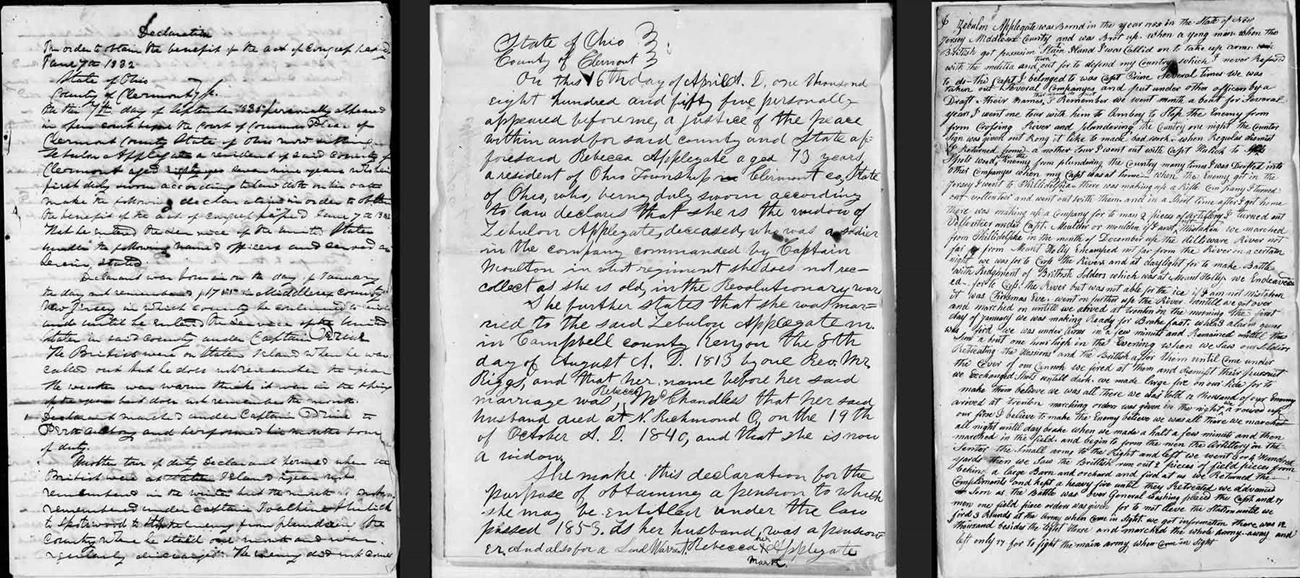

1832 – Eligibility requirement lowered to at least six months of service meaning militia service is eligible

Pension applications filed under the Act of 1832 hold great potential to discover new details and stories about the Revolution. Eligibility was no longer limited to regular army soldiers of the Continental Line. Anyone who served at least six months was eligible to apply meaning state militiamen were eligible.

Records kept by militias were incomplete at best. Rather than issue paper certificates of discharge, militiamen were often discharged verbally, leaving no documentation of their service. As a result, veterans applying under the Act of 1832 were required to appear before a Court of Record and provide oral testimony about their service by answering a standard series of War Department questions (“interrogatories”) corroborated by at least one credible witness.

US War Department questions posed to veterans included

- Where were you living when you were called into service; Where have you lived since the revolutionary war; and where do you now live?

- How were you called into service; were you drafted, did you volunteer, or were you a substitute? And if a substitute, for whom?

- State the names of some of the regular officers who were with the troops where you served…and the general circumstances of your service.

1836 – Widows become eligible

In the last series of Pension Acts, beginning in 1836, widows of veterans married before the end of the Revolutionary War in1783 were eligible to apply for pensions.

Widows were required to appear before a Court of Record to provide oral testimony about their husband's service, present proof of the marriage, and corroborate stories with credible witnesses. These women’s stories hold exciting potential to reveal new information through their first-hand accounts and experiences of their families during the Revolutionary War.

Sarah Martin recalls the trauma of having her house plundered by the British in Woodbridge, New Jersey. British soldiers threatened to shoot her child if she didn't cook them eggs.

National Archives and Records Administration

Pension Office Investigation Documents

Documents created by the Pension Office as they investigated a veteran's or widow's case are also included in each file. This may include timelines that map out a veteran’s length of service to see if the claimant met required time, letters between Pension Office officials to the veteran, widow and their lawyers or representatives. The correspondence is typically a request for clarification or additional supporting information. Often, a veteran would be asked to submit one, two, or even three additional amended or supplemental testimonies to resolve outstanding questions.

Pension Certificate and Accounting Documents

Sometimes, the pension certificate approving a claim will be in the file, accompanied by payment documentation such requests to transfer an account from one state to another when a veteran moved.

Supporting Documents

Documents submitted to support pension applications are among the most personal and compelling.

- Marriage Documents: To prove marriage to a veteran, widows often included family registers in their applications (in what must have been a heartbreaking moment) by tearing handwritten family trees out of family Bibles. Others submitted beautiful Frakturs illustrating their family story, and even small printed wedding certificates.

- Military Documents: Other applicants submitted original paperwork from the war. An officer might submit his original commission or orders received. Other soldiers submitted to the Pension Office the original discharge signed by General Washington they received at the end of the war when the army was furloughed at Newburgh, NY in 1783.

- Wartime Letters: Original wartime letters written in camp on active service are among the rarest documents.

- Diaries and Journals: Records include about 70 journals, diaries, and account books kept by soldiers during the Revolutionary War. NARA’s guide to the Revolutionary War Pension and Bounty-Land Warrant Application Files has information about diaries and journals in the pension files, beginning on page 14.

National Archives and Records Administration

Get Started!

We hope you are inspired to transcribe these records to experience the joy of historical discovery and make a permanent contribution for the nation’s 250th anniversary, or simply follow this project. With 80,000+ files containing more than two million documents, who knows what other treasures await? You could be the one to discover them!

Make a permanent contribution to the historical record by registering as a volunteer with the National Archives. Add "NPS" to the beginning of your username to be counted as a National Park Service referral. For example, NPSNatalieM.

Braisted, Todd. "A Patriot-Loyalist: Playing Both Sides." The Journal of the American Revolution April 7, 2014. https://allthingsliberty.com/2014/04/a-patriot-loyalist-playing-both-sides.

Crackel, Theodore J. "Longitudinal Migrations in America, 1780-1840: A Study of Revolutionary War Pension Records." Historical Methods 14, no. 3 (Summer 1981): 133-137.

Crackel, Theodore J. "Revolutionary War Pension Records and Patterns of American Mobility, 1780-1830." Prologue: The Quarterly of the National Archives and Records Administration 16, no. 3 (Fall 1984):155-167. https://www.archives.gov/publications/prologue/1984/fall/pension-mobility.html.

Dann, John. The Revolution Remembered: Eyewitness Accounts of the War for Independence. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1980.

Davis Heaps, Jennifer. "'Remember Me': Six Samplers in the National Archives." Prologue: The Quarterly of the National Archives and Records Administration 34, no. 3 (Fall 2002): https://www.archives.gov/publications/prologue/2002/fall/samplers-1.html.

National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives Microfilm Publications Pamphlet Describing M804 Revolutionary War Pension and Bounty-Land-Warrant Application Files. Washington: General Services Administration, 1974. https://www.archives.gov/files/research/microfilm/m804.pdf (PDF ~5 MB).

Nudd, Jean. Using Revolutionary War Pension Files to Find Family Information. Prologue: The Quarterly of the National Archives and Records Administration 47, no. 2 (Summer 2015): https://www.archives.gov/publications/prologue/2015/summer/rev-war-pensions.html

Rees, John U. "They Were Good Soldiers": African-Americans Serving in the Continental Army, 1775-1783. Warwick: Helion & Company, 2019.

Resch, John. "Federal Welfare for Revolutionary Veterans." The Social Service Review 56, no. 2 (June 1982): 171-195. https://www.jstor.org/stable/60000115.

Resch, John. "Politics and Public Culture: The Revolutionary War Pension Act of 1818." Journal of the Early Republic 8, no. 2 (Summer 1988): 139-158. https://www.jstor.org/stable/3123809.

Resch, John. Suffering Soldiers: Revolutionary War Veterans, Moral Sentiment, and Political Culture in the Early Republic. Amherst: University of Michigan Press, 1999.

Schultz, Constance. "Daughters of Liberty: The History of Women in the Revolutionary War Pension Records." Prologue: The Quarterly of the National Archives and Records Administration 16, no. 3 (Fall 1984): 139-153.

Schultz, Constance. "Revolutionary War Pension Applications: A Neglected Source for Social and Family History." Prologue: The Quarterly of the National Archives and Records Administration 15, no. 2 (Summer 1983): 103-114.