Last updated: April 8, 2021

Article

What Lies Beneath: How Electrofishing and Environmental DNA Is Being Used to Monitor and Conserve Fish Species in Great Smoky Mountain National Park

Gary Verholek Photo

As the fisheries biologists reach their surveying site, they are greeted with an original Smokies soundtrack of talkative squirrels and tufted titmice. Listening to the soundtrack and breathing in the nostalgic smell of organic matter from the stream, the team gets to work. They put on their waders, strap on their backpacks, and stretch their nets across the water. To the naked eye, it may seem as these rangers are here to play some sort of water sport, but this is the way that they check the vital signs of 2,900 miles of streams that pulsates through the heart of the mountains. It would be quite the overhaul to survey 2,900 miles of stream. Instead, they annually monitor 35 sample sites throughout the park. These 100-meter (1/16th of a mile) sample sites include runs, riffles, pools, and complex habitat, which represents a typical segment of that stream. These surveys are important because they help us understand the important ecosystems of the park but also, “what lies beneath.”

NPS Photo

What is Electrofishing?

Slowly but surely, fisheries biologists scan the calm waters of Abrams Creek. A small clicking sound can be heard buzzing from the creek but not from the dragonflies, stoneflies, or caddisflies but from the small backpacks that send 400-700V AC of electricity through the water, which results in stunning or immobilizing fish long enough for fisheries biologists to capture them with a net. This technique is known as electrofishing. Acting as doctors and the fish their patients, fisheries biologists capture, weigh, measure, and place each fish in a holding area until they are ready to be released. By making three passes through a section of the stream, or performing this process three times, according to fisheries biologists, Matt Kulp and Caleb Abramson, “Fisheries biologists can collect 65-70 percent of the stream’s population and during this process.” You may be asking yourself, “how harmful is electrofishing to the organisms that live in the stream?” There is a small level of discomfort that fish may have during a survey, however, mortality rates from electrofishing are very minimal (<4%) to fish in the park and electrofishing has little to no impact on non-target organisms such as salamanders and crayfish.

The health of these important stream ecosystems can be determined through the trout, darters, suckers, shiners, and other fish that live there. Maintaining healthy stream ecosystems also benefits other species such as salamanders, raccoons, otters, herons, and humans but there is always a nemesis lurking in the depths and shadows of a Smokies stream. In this case, that nemesis is non-native and invasive populations of fish such as Rainbow Trout that cause havoc by outcompeting native species for resources. These species are the equivalent of a human’s body being ravaged by a virus. Electrofishing acts as a deterrent by identifying these invaders but also helps monitor the expansion and contraction of their range in portions of the stream. Although electrofishing has been used to evaluate stream health for decades, there’s recently been a what-if-in-the-world wonderment about another technique, and that technique is environmental DNA or eDNA.

Environmental DNA: The Things They Carried

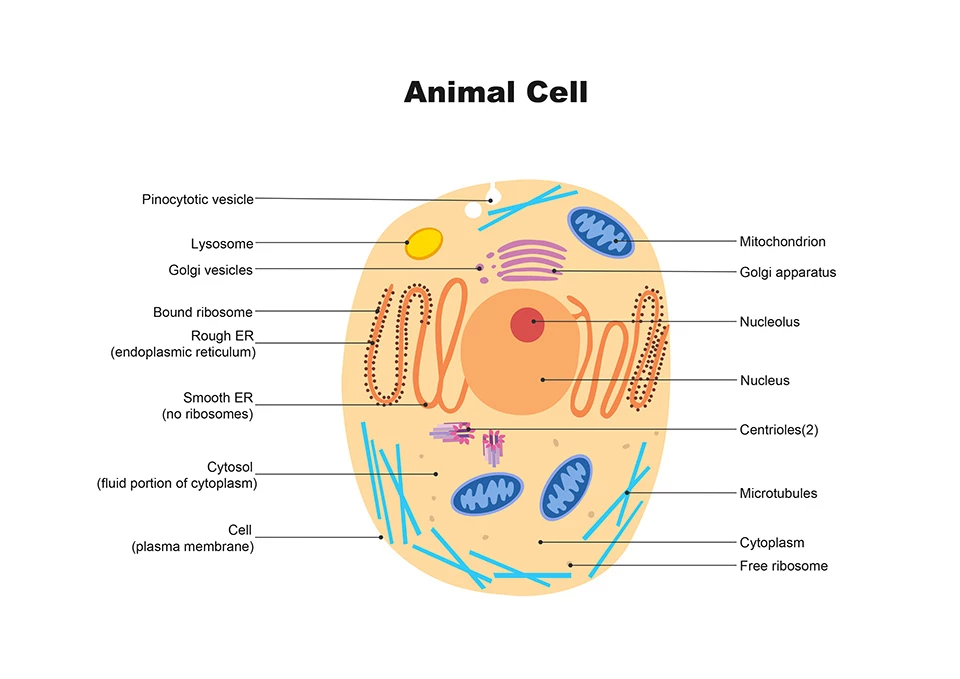

The waters are not as calm when Georgia College and State University researchers visit Abrams Creek. Unlike the hums of small electroshocking backpacks, two car batteries are on opposite sides of the stream. Yes, two car batteries are used to pump water from the stream, through a filter, and into a bucket. Once enough water is filtered, researchers carefully remove and freeze the filters for their next steps in the laboratory. Researchers are hoping to discover Environmental DNA or eDNA. Environmental DNA is what every organism in this world sheds in the environment. For instance, recently shed mucous cells from salamanders, skin cells from crayfish and insects, and scales and slime from fish in Abrams Creek fall under the umbrella of eDNA. Environmental DNA can also be captured from the past. Scientists have used deep ice core samples to study plants and arthropods from southern Greenland between 450,000 to 800,000 years ago. Scientists hope that species detection through eDNA will prove to be a less invasive and more efficient method for surveying life in a stream.In the laboratory, researchers work as mad scientists using an assortment of chemical solutions to extract eDNA from the samples taken from Abrams Creek. Next, researchers used polymerase chain reaction (PCR) primers to amplify or make millions if not billions of copies of specific deoxyribonucleic acid or (DNA). DNA is the hereditary material of humans and other organisms such as fish. Two types of DNA can be discovered in a cell. Nuclear DNA (nDNA) in the cell’s nucleus and mitochondrial DNA (mDNA) in the cell’s mitochondria region. This is important when it comes to animals since they carry more mDNA than nDNA. When PCR primers are used to amplify mDNA, it results in better detection of target species. This eDNA can then be searched in an International Barcode of Life program (iBOL) database. A database that stores data on thousands of species that have been surveyed. Imagine if each fish in a stream had a barcode located on its belly and you were able to scan that barcode to identify the species that you caught. That is the premise behind the iBOL database.

Wondershare Photo

NPS Photo

Does It Measure Up to the Hype?

As researchers patiently wait for the results from the eDNA survey, the suspense could not be more intense. What will this filter of eDNA tell us about the species the lurks in the Smokies? Unfortunately, although results identified many common species of fish, the results did not tell researchers about the next great discovery. Matter of fact, there was only one instance during the survey that eDNA picked up the presence of identical species of fish as the electrofishing data. While a 2015 survey showed that eDNA could an effective at identifying fish species in Abrams Creek, electrofishing is the best way that we can keep a pulse on our wonderful streams of the Smokies but eDNA has the potential to help us conserve our world.

“So, What Does eDNA Tell Us?"

So, what lies beneath? What lies beneath is the understanding that electrofishing is presently the best technique to monitor, conserve, and discover current and new fish species in the Smokies but the future does not exclude the potential of using eDNA in the Smokies and in the world. Using both techniques could not only help monitor the pulse of 2,900 miles of streams in the park but can also expand the biodiversity beyond our imagination, helping us potentially discover aquatic life that has been living the Smokies for hundreds or thousands of years. Imagine, the next great discovery could only be a small water sample away.