Last updated: November 22, 2021

Article

What is a Coral?

Caroline Rogers

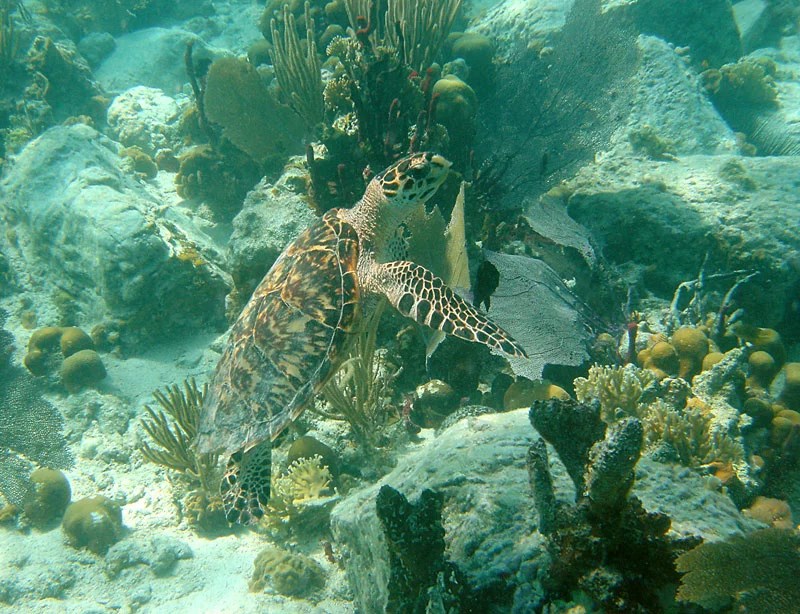

St. John is beautiful----above and below the water. Much of the beauty in the sea surrounding the island is from coral reefs and the colorful fish, sea turtles, and sea stars that live in and around them. But what, exactly, is a coral? There is nothing like a coral on land. Is it a rock, a plant or an animal?

The Great Barrier Reef, extending 1300 miles along the eastern coast of Australia, is the largest natural structure on the planet. This reef and all others including those around St. John exist because corals are solar-powered animals that create a complex physical framework. They are the architects of the reefs. The symbiotic relationship between the corals and the microscopic algae in their tissues results in the secretion of limestone rock (calcium carbonate) in a process called calcification. The coral animal receives nutrition from the algae (called zooxanthellae), and the algae photosynthesize within the protection of the coral tissues, using carbon dioxide and nutrients from the coral animal.

Corals form true reefs when they grow close together and deposit layer after layer of limestone, several feet high. Many different kinds of fish depend on coral reefs for food and shelter—places to hide from voracious predators like sharks, groupers and snappers. Octopuses make dens under corals, and Hawksbill Sea Turtles eat sponges growing on the reefs.

Caroline Rogers

Some corals are single individuals, but most are colonies. The word “colony” often confuses people—it simply refers to a group of coral polyps, often joined together at their bases. Each polyp is like an anemone. Anemones are closely related to corals but do not secrete limestone skeletons.

Caroline Rogers

Caroline Rogers

When you walk along the cobble beach around to the east from Salt Pond Bay towards Ram Head you see bright white rocks with interesting patterns—ridges, grooves and starlike-holes—mixed in with the black and dark gray boulders cast up on shore. These white “skeletons” are what remains when corals die.

Corals are differentiated into separate species based mostly on the characteristics of their skeletons. Corals range in size from just a few inches to over 12 feet high or across. Some of the largest colonies around St. John are Boulder Star Corals and Pillar Corals.The Boulder Star Coral, the most abundant coral growing on the reefs around the island, has been hit particularly hard by bleaching and disease. While it is still the dominant coral on the reefs, many of the colonies have died. It is unusual to see an intact colony in good condition.

Most coral species, including Elkhorn, Staghorn and Boulder Star Corals, release male and female gametes (sperm and eggs) into the water. The gametes fuse and develop into larvae that are transported far from the “parent” colonies. These are called “broadcast spawners.” Some species have internal fertilization, in which eggs are retained inside the polyps and fertilized by sperm that were released into the water column. The larvae of these “brooding corals” sometimes settle close to the parents. Coral larvae, only about the size of a pinhead, need to settle on hard surfaces, like dead coral, to survive. Parrotfish eat algae that can grow over small corals.

Caroline Rogers

Corals are carnivores that eat zooplankton. Like many other animals in their Phylum (Cnidaria) and Class (Anthozoa), their cells have specialized stingers with barbs (called nematocysts) that can stun their prey—tiny shrimp and other crustaceans. A few corals like Finger Coral and Pillar Coral extend their polyps during the day, giving them a fuzzy appearance. Most corals extend their polyps at night when feeding.

High light and high seawater temperatures lead to coral bleaching—the breakdown of the symbiotic relationship with a loss of the zooxanthellae, and the coral appears bleached (pale or white). Bleached corals are still alive but will eventually die unless the water becomes cooler. In 2005, bleaching associated with the highest seawater temperatures on record, and a subsequent outbreak of disease killed about 60% of the corals around St. John, St. Croix and Puerto Rico. Recently coral diseases have become more of a concern worldwide. In 2010, many corals around St. John bleached, but no disease outbreak followed. The corals at least on some St. John reefs have begun to recover, but corals grow very slowly and if recovery occurs it could take decades. The Boulder Star Corals, the most abundant on St. John reefs, only grow about 4/100 of an inch a year—the width of a dime. The fastest growing corals, like Elkhorn and Staghorn, only grow several inches a year.

Global climate change is expected to raise seawater temperatures, leading to more bleaching episodes. Climate change is also expected to make the ocean more acidic, which could cause corals to dissolve. Some scientists even think that reefs could collapse this century unless the greenhouse gases that are driving climate change can be brought under control! In addition, scientists predict that major storms will become more frequent. Tropical storms and hurricanes can smash corals, especially the more fragile branching corals like Staghorn and Elkhorn. Storms can overturn and break corals to depths of 60 feet or more. Some of the coral branches or fragments can land on hard substrate and begin to grow. However, if the corals are damaged too much, the fragments will not survive.

The peak of hurricane season, August and September, occurs when seawater temperatures are usually at their highest. Surprisingly, major storms can sometimes be beneficial because they often lower seawater temperatures, making it less likely that corals will bleach.

Caroline Rogers

We need to learn more about how St. John’s reefs are linked to other reefs in the Caribbean. Research on currents and on the different genotypes (genetic makeup) of corals reveals that some of the Elkhorn Corals on St. John grew from larvae that came from Buck Island Reef National Monument, St. Croix, while others developed from larvae from as far away as St. Vincent and the Grenadines. The “connectivity” among reefs throughout the Caribbean is an active area of research. If reefs that are the source of the larvae of corals, fish and other reef species deteriorate, then “downstream” reefs could suffer. Coral reefs are the most diverse marine ecosystems, with an estimated 1 million species, only about 10% of which have been identified. We may be losing species that haven’t even been discovered, including some that could benefit people. Natural products from some reef species can help fight cancer and other diseases.

Caribbean corals are usually various shades of brown, gray, green and yellow, while corals from the Indo-Pacific can be brilliant blues, purples and pinks. The colors come from pigments in the coral animals and in the zooxanthellae. At least some of the pigments appear to protect the corals from high light levels, especially in very shallow water. Recently, some scientists have started to try to synthesize the natural sunscreens found in corals for use by humans. Some of the chemicals in sunscreens now on the market harm corals. It is better to use products, for example with zinc, that physically block the sun’s rays.

People can’t control hurricanes, diseases, and bleaching, of course, but they can avoid inflicting other damage on corals from careless anchoring and releasing of pollution and sediments into reef waters. Corals are the fragile foundation of extraordinarily beautiful coral reefs that protect shorelines from erosion, support the highest biodiversity of any marine systems, and provide many products that can improve the lives of people.