Last updated: September 27, 2022

Article

Seeking Closure: Sarah Ruth's Effort to Discover What Happened to her Son Amos at Gettysburg

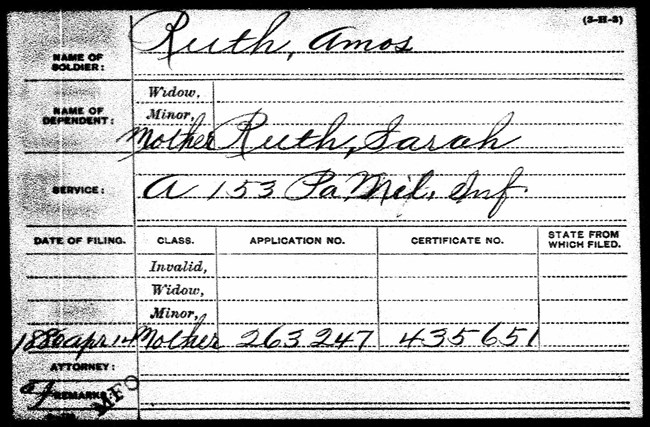

Shortly after the Civil War, Federal veterans were able to apply for military pensions provided by the United States government for their service. Those who lost their husbands or sons could also claim a pension with proof of their soldier’s death. Today, these pension files are widely used by researchers and genealogists. In the case of Amos Ruth, a private in the 153rd Pennsylvania listed as killed on July 1 at Gettysburg, an application for a pension created a multitude of questions. Amos was listed in some documents as killed, where in others he was listed as wounded and discharged with the rest of his regiment on July 23, 1863.[1] His mother, Sarah Ruth, applied for a pension, but an investigation was launched years later to learn what happened to Amos Ruth and to make sure that Sarah was not committing pension fraud. Sarah was not the only one affected by the disappearance of Amos, his younger brother William was also looking for answers. The two brothers served together during the battle, but William was unsure of his brother’s fate.

Amos and William Ruth were from Nazareth, Pennsylvania and worked as farmers. William was the younger of the two, born on June 5, 1843; Amos was three years older. By 1862, the brothers had moved from their parents’ home, but only a couple blocks away. They decided to stay close since their parents recently separated after a divorce and neither parent remarried. Before the brothers enlisted, they helped their mother, Sarah, as much as possible. Before the brothers decided to enlist, Amos gave his mother money before they departed in 1862. He also told his employer to give his mother his remaining wages if he did not return.[2]

Image reproduced courtesy of Northampton County Historical and Genealogical Society

The Ruth brothers both joined Company A of the 153rd Pennsylvania in September 1862 with their neighbors Cyrus Frace and Reuben Vogel.[3] The 153rd PA was as a 9-month regiment, compared to many whose term of service was for “three years or the course of the war.” The Ruth brothers, along with their neighbors, marched into Virginia in late November. They had their baptism by fire at the Battle of Chancellorsville in May 1863, from which the Ruth brothers emerged unscathed. The regiment’s nine-month term of service was coming to close during the Gettysburg Campaign, as the Army of the Potomac chased after the Army of Northern Virginia. As they returned to their home state, the Ruth brothers did not expect the homecoming they received. Under heavy artillery fire, the 153rd PA and elements of the 11th Corps arrived at Blocher’s Knoll (later known as Barlow Knoll) to prevent Confederate forces from reaching town. Skirmishers were sent forward to scout the woods to their front.

Amos was selected to go with the scouts into the woods in front of Blocher’s Knoll. When asked about this years later, William reflected, “When the fighting commenced, we were in different squads and were separated but were not very far apart. I know that he gave me some tobacco when we were going into action. When we were separated into the battle it was the last time that I ever saw him."[4] Within minutes, Confederate forces fired a volley into the ranks of the 153rd PA and forced the skirmishers to retreat. When they arrived back with the regiment, Amos was absent. William had little time to process what had just happened when Confederates suddenly pushed through the tree line and attacked their position. The defensive position broke, forcing the regiment to retreat. During the retreat, William was hit twice in the back of the left shoulder, one in the collar bone, and one below the neck. Unable to carry himself off the field, William was left behind, laying wounded upon the field until July 4. He was taken to the 11th Corps field hospital and was treated for his wounds. He lost the use of his left arm and was transferred to a hospital in Harrisburg on July 5.

Soon William, “began to inquire for him (Amos) but nobody that I saw could tell me anything about him. It was I that was in the hospital there and not he. I thought first that he might have been taken prisoner but the paroled prisoners that came to Harrisburg said that this was not the case, that he had not been taken prisoner.”[5] The younger of the two brothers was left wondering for years what happened to Amos. He assumed he was dead; killed in action and buried on the Gettysburg battlefield. William mustered out with the rest of the regiment on July 23, 1863 without locating his brother. He returned home to Nazareth, PA to inform his mother of the grave news.

NPS Photo

It was not until 1890 that Amos's story reemerged, ten years after his mother filed a pension under his name.[6] There is unfortunately no documentation on why Sarah waited to file a pension under Amos’s name as late as she did. Based on the history of Civil War Pensions, the process was complicated due to the constant passing of laws that changed the amount a pensioner received and who was eligible to receive one. However, one qualification was certain, there had to be evidence or an eyewitness to prove what happened to the soldier in order to receive a dependent’s pension.[7] Without knowing what happened to Amos at Gettysburg, the Pension Office had no proof of Amos being killed in action on July 1. After further investigation, the Pension Office asked for testimony to find out what happened to Amos Ruth. Members of the 153rd Pennsylvania Infantry closest to Amos were asked to provide a deposition for what happened to him so his mother could continue to collect his pension.

One of the first veterans asked to provide testimony was William Ruth. He stated that he was Amos’s brother and the claimant’s son, served in the same company, regiment and was where Amos was during the battle. He recounted his brother giving him tobacco before the fight but mentions he was wounded and left on the field overnight. He described looking for his brother but coming to the realization that he was killed in action. “My own belief is that he was killed and buried by the Confederates and when he was taken up again he was so much decomposed that no one could recognize him any more in fact, those that were not buried until the fourth day were black so that one could hardly tell them anymore.” William’s deposition explained what he knew and identified others who could talk more about what happened on July 1, 1863. He provided the names of William Kiefer and Henry Hagenbush, Amos’s tentmates, who would presumably know more about the event. The investigation brought out some emotions from William about his older brother, “I was satisfied that my brother was killed at the Battle of Gettysburg. If he was living, I was satisfied that we would have seen him.”[8]

The depositions continued after William Ruth’s account since he did not witness Amos’s death. So the investigator approached the next available witness, William Kiefer. During the battle, Kiefer was wounded, taken prisoner, and then paroled from the action on July 1. He remembered Amos before the war but became closer when they enlisted in the 153rd PA together. He recounted that Amos: “was the third man from me on the left and was forty or fifty yards from me. When the first firing began the shots were scattering but when the enemy came close enough, they fired a volley into us, and he fell on the first fire. At the same time that the volley was fired a shell exploded where he was, and he fell forwards and a little towards me. I can’t tell which killed him as the volley and the shell struck us at the same time, but I saw him fall and that is the last I saw of him.”[9] He continued that he did not check to see if Amos was dead since they had to retreat from the field. Even though some men speculated Amos was captured, Kiefer was among those who were captured and did not see him. Kiefer’s deposition is probably one of the most credible, since he wrote one of the regimental histories for the unit. The unfortunate news Kiefer delivers at the end of his deposition is that Henry Hagenbush, the man that saw Amos in his final moments, died two months before their interview with him.[10] Hagenbush’s deposition could have brought the family closure to what happened to Amos, ending the investigation.

National Archives and Records Administration

The depositions given by William Kiefer and William Ruth provided the best picture of what happened to Amos on July 1. The investigation stalled with the loss of Hagenbush, who witnessed the event described by Kiefer and Ruth, but others stepped forward to clarify. B.F Shaum, Valentine Heller, and J.L Boerstler appeared before investigators to confirm the story that Amos was killed on July 1 and his body was never recovered. B.F Shaum was the commander of Company A and confirms that Amos was present for roll the morning before the battle. He took roll once the battle was over and Amos was listed as killed from the fight.[11] Shaum does not discuss seeing him after roll call due to his wounding and being left on the field until the battle was over. He only hears of Amos’s death through soldiers that continued the fight after July 1. Shaum’s statement is rather brief, but the accounts of Valentine Heller and J.L Boerstler provide the necessary details Shaum was unable to provide.

Valentine Heller’s story was very similar to Kiefer’s account. “[T]he last that I saw of him was where we were out there together,” remembered Heller. “After the first volley we had to retire, and I have no doubt but that he was killed then.”[12] J.L Boerstler also remembered, “I saw Amos Ruth fall. I don’t remember whether he fell after the company had received a volley by the enemy and I can’t say whether a shell exploded before them. The only thing I know is that I saw him fall.”[13] However, Boerstler could not confirm if Amos was wounded or killed, only the fact that he fell on the field. He did mention that when he arrived at the Harrisburg hospital, he did not see him there or any time after the regiment’s mustering out. Both Heller and Boerstler saw Amos Ruth fall on the battlefield, like Kiefer’s account, but cannot confirm what wounded/killed him. To further matters, they could not confirm if Amos was located after the battle.

After five depositions from members of Company A, 153rd Pennsylvania Infantry, the fate of Amos Ruth seems certain but not confirmed. The accounts William Kiefer, Valentine Heller, and J.L Boerstler, all mention the same timeline of events. Company A was called to the front as skirmishers near Barlow’s Knoll. The five men and Amos Ruth were spread out nearly 30 to 50 yards apart from each other when Confederate Infantry fired a volley into their ranks. Around the same time, a shell exploded to the front of Amos Ruth and he fell from the results of the volley or the shell. Much of the company were either wounded or later captured during their fight on July 1. When William Ruth was brought back to the XI Corps field hospital, no one in the regiment knew were Amos was. After William’s transfer to Harrisburg, both the patients in the hospital and those released on parole confirmed that Amos Ruth was not amongst them. All five deposition writers believe that he was killed on July 1 and his body was never recovered.

The story of Amos Ruth is not uncommon. The chaos of battle and the lack of identification items, like dog tags, made it difficult to identify soldiers after the smoke cleared. Even if a soldier received a proper burial, many families could not make the trip to recover their loved ones or by the time they did, they were unable to locate them. For Amos Ruth, the investigation provided a chance for the family to finally know what happened to him. The only concern about the conclusion of Amos’s story is that most of the soldiers questioned are asked for detailed specifics nearly thirty years after the battle ended. The men were fighting for their lives and some left wounded on the field, trying to find their own way out of a desperate situation. The fact present may not be completely accurate as memories of the battle faded with age. The investigation by the Pension office opened some wounds, especially with William Ruth. They tried their hardest to give closure to not only Amos’s mother Sarah, but also to William, who never saw his brother after the first volley. The depositions and statements in this case turned the favor toward Sarah Ruth to collect the pension for her son.[14]

Amos Ruth’s pension file provides us with a glimpse of what might happened to him on July 1 at Barlow’s Knoll. His body was never located, but his story lives on through these files and through the memories of his comrades. Many of the soldiers killed on July 1 were reinterred into the National Cemetery as unknowns, where Amos’s might rest today. The pension files show the impact of the war on young families and future generations. Though families were compensated for their loss, nothing could fill the void created by the absence of their loved ones.