Last updated: December 14, 2023

Article

A Story Written on the Land: Recovering the Site of Werowocomoco

Werowocomoco Research Group

Matt Rath

Excerpted from "Virginia Indians at Werowocomoco: A National Park Handbook", second edition:

On February 15, 2003, a parcel of land along Virginia’s York River was wrapped with the quiet of a deep winter day, save for a breeze off the river that picked up speed as the sun traveled the sky. Across the fields, along the woods and the shoreline of Purtan Bay, the human footsteps of a small gathering made history. Virginia Indians, representing seven tribes, were among this group, marking the largest—and possibly first—native presence at this site in some 400 years. Yet Indians had hunted, fished, and raised families on this land for thousands of years. Over time, it became a seat of power for Virginia Indians and the site of interactions with European colonists that would reshape lives for generations to come. This place was and, in many ways, remains Werowocomoco.

On today’s maps, Werowocomoco can be found in Gloucester County, Virginia, on the north side of the York River. Nothing above ground remains of the Indian community that lived here. The rural landscape is largely intact, however, and clues to the past still lie in the earth. Fields and forests at the site surround a private, single-family home, situated at the end of a long gravel road with a view of Purtan Bay and the York River beyond. In the early 1600s, this river was known as the Pamaunke, and today some believe that Werowocomoco was a political and spiritual center in the Tidewater Indian world.

Indians moved away from Werowocomoco in 1609. In the centuries that followed, Indian heritage was both neglected and suppressed. While historians and others kept the memory of Werowocomoco alive, knowledge of its story faded. Scholars of indigenous cultures still associated the settlement with the north shore of the York River, but its exact location was no longer clear.

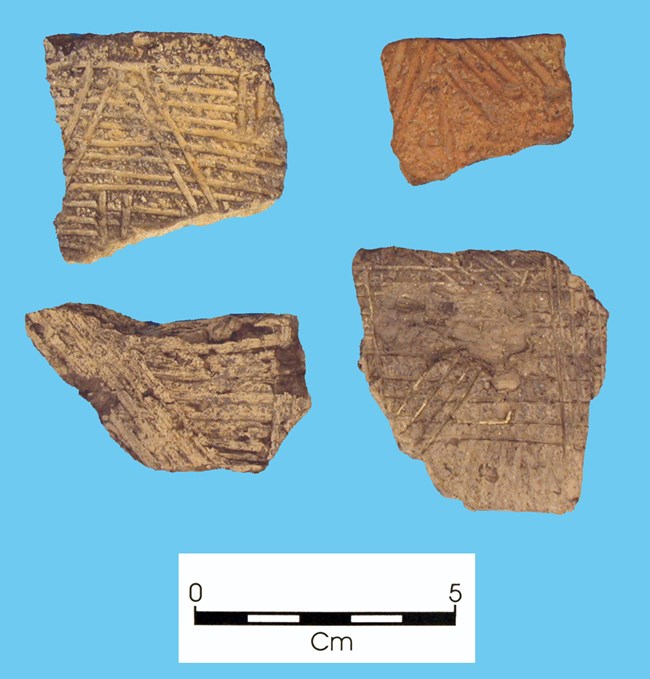

Werowocomoco Research Group

And then, in 2001, Werowocomoco surfaced once again. Archeologists Thane Harpole and David Brown of the Fairfield Foundation paid a visit to Bob and Lynn Ripley, who lived on the York River at Purtan Bay. Lynn Ripley had an impressive collection of artifacts from their land. The Ripleys’ garage was a workspace for sorting pottery fragments and projectile points, most of which she had gathered from the eroding shoreline. Harpole and Brown, who knew that Werowocomoco might have been at this location, immediately saw the significance of the artifacts. They contacted Randolph Turner, an archeologist at the Virginia Department of Historic Resources. Their exchange was the start of a partnership between the Ripleys, archeologists, and Virginia’s Indian communities. Together, this partnership restored native connections to Werowocomoco and directed respectful scholarship to the deep history of the site.

Werowocomoco—translated in the general sense from the Virginia Algonquian language as “place of leadership”—was the residence of a powerful political and spiritual leader known as Powhatan. His daughter Pocahontas could be found there too. Scholars believe that, beginning in the late 1500s, Powhatan established a chiefdom that may have influenced dozens of communities and their leaders along the rivers of the southern Chesapeake Bay. Among them were the ancestors of several contemporary Virginia tribes, including the Pamunkey, Mattaponi, Upper Mattaponi, and likely the Nansemond and Rappahannock as well. The Chickahominy were located near the center of the chiefdom but remained independent of it and did not pay tribute to Powhatan.

Werowocomoco Research Group

In the spring of 1607, English colonists arrived on a neighboring river, now named the James. A few Europeans had explored the Chesapeake before, but this was a larger group and they aimed to stay. The colonists built a stockade on the edge of a swamp and named it James Fort. It would soon become Jamestown, the first permanent English settlement in North America. But in the early 1600s, the future of the colonists, the Virginia Indians, and what would become the United States was not only unwritten but very much uncertain. Within a span of decades, their stories would change dramatically. The people who walked the shores of Werowocomoco witnessed events that Indians, scholars, and curious visitors continue to ponder and question today.

Captain John Smith, an English leader of James Fort, wrote that he met Powhatan and Pocahontas when he was captured and brought to Werowocomoco in December 1607. Their meeting marked the beginning of escalating interactions between Indians and colonists that ranged from cautious and friendly to confusing and violent. By 1609, more of the English had arrived and continued to demand food from the Indian harvests. The Indians were increasingly unwilling to trade and wary of English intentions. Attempts at cooperation steadily led to conflict, and Powhatan moved his headquarters farther inland. Werowocomoco soon fell silent.

The land at Werowocomoco was then cultivated for crops and timber from the early days of colonial Virginia, either by a single family or small cluster of neighbors. There is no indication that they maintained any direct association of the land with Werowocomoco or its importance to native and colonial history. Through the centuries, its identity as a native place echoed mostly through the ink of colonial explorers, who had recorded its location on hand-drawn maps and in personal accounts of events in and near the site. The Indian perspective on Werowocomoco was not documented, and its story was largely overshadowed by the unfolding of a new nation that, in celebrating its own history, often dismissed the history of those who preceded it.

Martin Sekula / Virginia Department of Historic Resources

Now, through a remarkable confluence of people, funding, research, and partnerships, Werowocomoco has begun to receive the attention it deserves. Its location has been pinpointed, explored, and honored. The Ripleys not only permitted archeological explorations, but also welcomed them. Between 2003 and 2010, archeologist Martin Gallivan of the College of William and Mary led a series of field sessions with support from the Virginia Department of Historic Resources, National Park Service, and National Endowment for the Humanities. The fieldwork has revealed the deep history of Werowocomoco—a history now known to have begun centuries before Powhatan ever lived there.

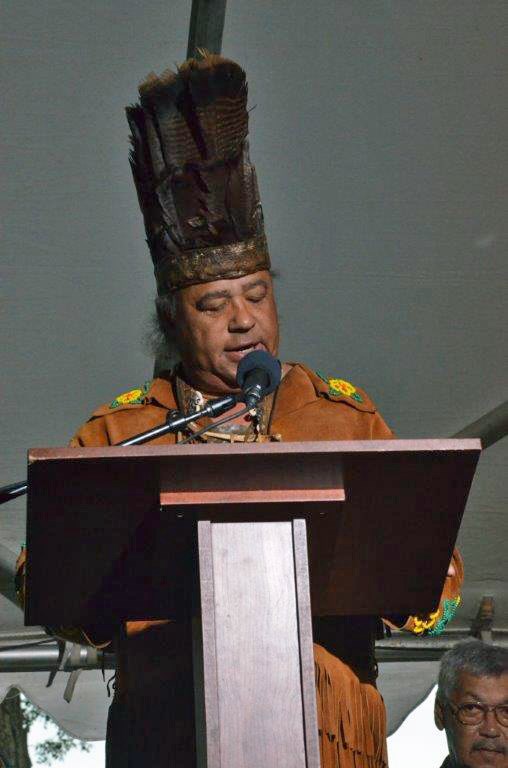

The Werowocomoco research team established an important partnership with Virginia Indians, an effort led by William and Mary professor Danielle Moretti-Langholtz. As a result, the work at Werowocomoco is the first archeological project to take place with the sustained guidance and participation of Virginia Indians. The project’s Virginia Indian Advisory Board included representatives from the Pamunkey, Mattaponi, Upper Mattaponi, Rappahannock, Nansemond, and Chickahominy tribes. Together, they have provided advice and feedback on research goals, public outreach, and the handling of artifacts. Virginia Indians also helped with the field investigations, while others have come to walk the land, tour the excavations, and spend family time along the shore.

Partners in the Werowocomoco project immediately recognized the need for long-term stewardship of the site. In 2005 and 2006, Werowocomoco was added to the Virginia Landmarks Register and the National Register of Historic Places. In 2012, the Ripleys placed an easement on approximately 58 acres of the property through the Virginia Department of Historic Resources. The easement is a legal agreement, attached to the property deed, which helps provide permanent protection for the land and its archeological resources. In 2016, the site was sold to the National Park Service, which is working to steward the land and its resources in cooperation and consultation with Virginia Indian tribes.