Last updated: August 23, 2024

Article

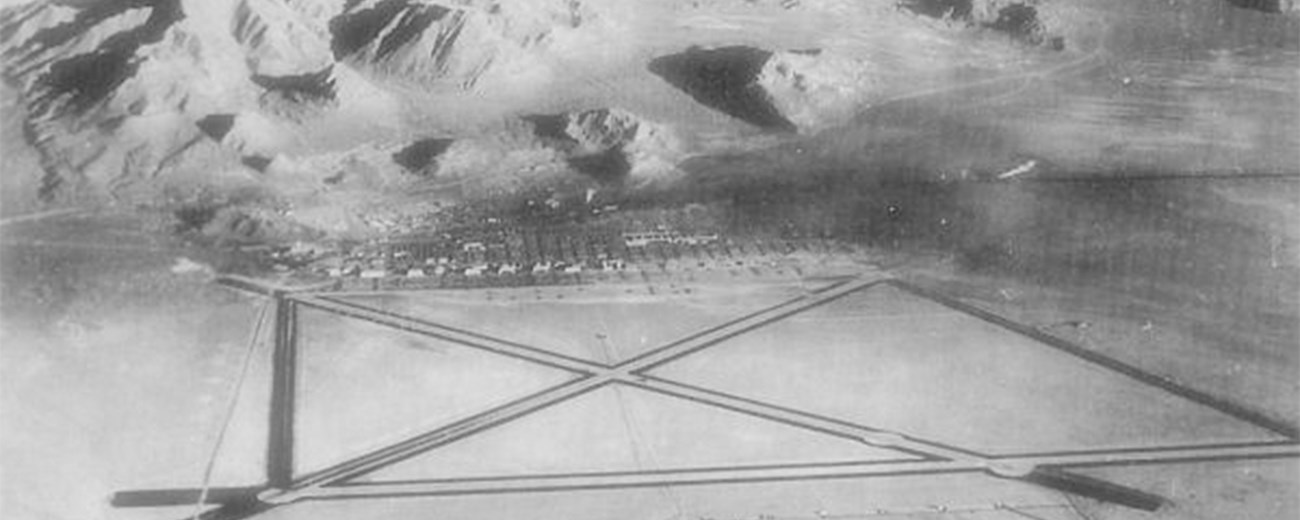

Wendover Air Base, UT

PUBLIC DOMAIN

In early September 1944, Lieutenant Colonel Paul Tibbets of the Army Air Forces, who probably knew more about the new B-29 bombers than any other pilot, was called to a closed military meeting. There he was put in charge of a secret project to prepare modified B-29s and their crews to be used delivering the atomic bomb to Japan, with the hope of ending the war. It would be known as the 509th Composite Group, and for security would be a self-contained unit, including not only the pilots and crews, but also repair and maintenance personnel and administrative staff. He was given his choice of three airfields: Wendover, Utah; Great Bend, Kansas; or Mountain Home, Idaho. Flying first over Wendover Air Field outside of Salt Lake City, he saw that it was just what he needed. It was remote, the runways would handle B-29s, and the hangars and maintenance facilities were in good condition. In addition, it was located along a rail line with a spur coming right into the base. This made it easy to deliver sealed shipments, and later to move out the materiel going to Advance Base, Tinian Island, in the Pacific.

Wendover had been established in 1939, with 1.8 million acres (737,000 hectares) for bombing and gunnery practice; it worked well for heavy bomber groups. After Pearl Harbor, Wendover became a key base for crew training. Several hundred barracks, hangars, and squadron buildings were built, and the first training unit arrived April 6, 1942. At its height it hosted 2,000 civilian employees and 17,500 military personnel and had 668 buildings and three 8,100-foot runways. These training programs ended in September 1944. When Tibbets arrived, it was basically empty. It was ready to begin its new secret role with the Manhattan Project, as a part of the Los Alamos Laboratory in New Mexico. For the 509th, it was within reach of Los Alamos as well as the site called “Sandy Beach”. This location, on the eastern side of the Salton Sea in California, was used for bomb flight and drop tests, and preparing bombing tables for the new planes. There was an air shuttle from Wendover to Los Alamos, via Kirtland Air Force Base in Albuquerque, for personnel and cargo.

The 509th consisted of 225 officers and over 1,540 enlisted men and was officially activated December 17, 1944. At a meeting that day, Tibbets told the men that they were there to work on a very special mission; they would be going overseas; they were taking part in an effort that could end the war; and everyone would be operating under maximum security. He had to convince the men that they could not give out a hint to anyone that the operation was different from any other in the military, although it certainly was. Mail and phone calls were monitored. Wendover was code-named Kingman, the Manhattan Project’s Site K; the work was called Project W-47. Los Alamos staff were not permitted to mention W-47 while in Los Alamos.

Wendover was ideal for testing and improving the bomb’s ballistic characteristics. The planes and crews practiced precision bombing, using a target that was a circle 400 feet in diameter. Bombardiers had to practice dropping the bomb from 30,000 feet, with accuracy to within 200 feet of the aiming point. Tibbets didn’t count a crew and navigator as being combat ready until they had made 50 practice drops. He insisted that they have practice bombs that were the size, shape, and weight of the real thing. Because of their shape, and because they were sometimes painted orange, they were called “pumpkins.” For target practice they were usually filled with concrete; eventually some were filled with conventional explosives and used against selected objectives, such as airfields, in Japan. The 509th received about 200 of the bomb casings. Besides the cases being used for crew practice, scientists from Los Alamos worked with them to modify the bomb configurations to allow them to fall accurately to the targets. The pilots and crews also perfected and practiced the “escape maneuver.” This was a 155-degree turn, done at full throttle the instant after an atom bomb was dropped, to allow the plane to get the maximum possible distance away from the bomb when it detonated. This required a degree of precision flying unfamiliar to bomber pilots, but after many practice runs the maneuver proved effective on the actual bombing flights.

The 509th moved to Tinian Island in June 1945. When they finished their work in the Pacific they didn’t return to Wendover; in November they were assigned to Roswell Army Airfield in New Mexico. There they became the nuclear strike and deterrence core of the Strategic Air Command. After the war the Wendover base was used for training exercises and as a gunnery range and research facility and was deactivated and reactivated several times. It was closed by the Air Force in 1969, given to Wendover City in 1977, and Tooele County took ownership in 1998. Today it is considered the most original and authentically preserved WWII Army Air Forces training base in the United States. There is a museum, with guided and virtual tours of the remaining buildings. The loading pits, used to get the bombs under the planes and into their bomb bays, still remain. It is considered a Tooele County public airport. Air shows and other activities take place there, and a local group, “Historic Wendover Airfield,” works to preserve the former base. Portions of the original bombing range are now designated the Utah Test and Training Range; with over 19,000 square miles (49,000 km2) of air space, it is used by the Air Force for live fire targets.

- Russ, Harlow W. Project Alberta: The Preparation of Atomic Bombs for use in World War II. Exceptional Books, Ltd. 1990. Los Alamos, NM.

- Rhodes, Richard The Making of the Atomic Bomb. Simon and Schuster, New York. 1986.

- Tibbets, Paul Jr. The Tibbets Story. Stein and Day, New York