Last updated: October 23, 2023

Article

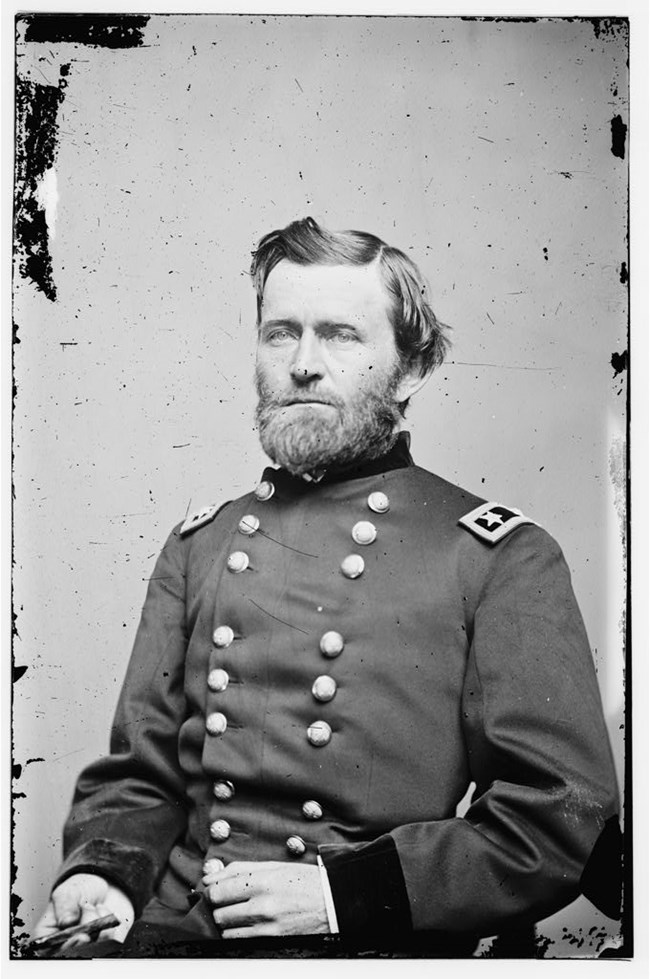

Was General Grant Surprised by the Confederate Attack at Shiloh?

Library of Congress

The Battle of Shiloh fought was the bloodiest battle fought during the American Civil War up to that point in the conflict. Fought on April 6-7, 1862, the two days of carnage led to around 23,000 casualties, making it the deadliest battle of the Civil War up to that point. The battle fundamentally altered Grant's perception of the Civil War and brought about charges of poor generalship against him personally. One persistent claim still debated today concerns whether Grant was surprised by the Confederate attack at Shiloh. Is there any truth to the claim?

Ironically, the first press accounts of the battle greatly exaggerated praise upon Grant. Shortly after the battle a correspondent named W.C. Carroll telegraphed an account of the Union victory to the New York Herald, but also included notes on Grant himself. “Grant in person had turned the tide, on the second day, by himself leading a desperate charge on the Rebel position, brandishing his sword ‘while cannon balls were falling like hail around him.’” However, a rival journalist named Whitelaw Reid wrote a scathing piece of equal exaggeration for the Cincinnati Gazette. He suggested that Grant’s army was surprised in its camps. He asserted that soldiers were asleep when the Confederates attacked, some were shot dead in their tents, and others were bayoneted in their sleep. He was highly critical of Grant and stated that he did not arrive on the field "until after nearly all these disasters had crowded upon us." The Governor of Ohio, hearing reports of Buckeye troops running away when the attack came, stated that his state’s troops were not cowards, but victims of "criminal negligence of the top command." The truth had to be somewhere in between these two accounts. Grant defended himself both then and later by saying that as soon as he heard that sounds of battle while starting breakfast on the morning of April 6th, he immediately cancelled his normal plans, issued orders, and rode to the front.

An important point to note is that General Grant never expected to fight a battle in the vicinity of Shiloh. According to historian James M. McPherson, Grant’s supervisory commander, General Henry Halleck, sent Grant "forward to Pittsburg Landing on the Tennessee River, twenty miles north of Corinth [Mississippi], and ordered [General Don Carlos] Buell to join him there with 35,000 additional troops. When the two armies were united, Halleck intended to take field command of their 75,000 men and lead them against Corinth." Pittsburg Landing was supposed to be a staging area for the true Union target, which was the strategic railroad hub at Corinth. Grant's Army of the Tennessee was divided on the 6th and one of his five divisions, under General Lew Wallace, was miles away at Crump's Landing. Grant worried about an attack two days before the battle of Shiloh, but not on his main body. If anything, he felt Wallace’s division at Crump's Landing was in the most danger of an attack. Writing to one of his other division commanders, Grant wrote that "it is believed that the enemy are reinforcing at Purdy, and it may be necessary to reinforce Gen. Wallace to avoid his being attacked by a superior force. Should you find danger of this sort, reinforce him at once with your entire Division." Of course, Grant’s prediction was mistaken once the main attack occurred on his main force at Pittsburg Landing.

Grant also noted skirmishing in the days preceding the main Confederate attack, but seems to have not taken these skirmishes as seriously as he should have. From April 3rd through 5th, Grant continued to cling to the view that the main battle would be in Corinth and not Pittsburg Landing. In a letter written on April 3 to Captain N. H. McLean, the Assistant Adjutant General of the Department of the Mississippi, Grant expected his army to advance on Corinth by Saturday the 5th. He also noted that captured Confederate deserters claimed that enemy forces at Corinth were "large and increasing." In a letter written to his wife Julia on the same day, Grant remarked that "soon I hope to be permitted to move from [Pittsburg Landing] and when I do there will probably be the greatest battle fought of the War." The letter to Julia is also important because it shows Grant as perhaps too overconfident about his forces. “I do not feel that there is the slightest doubt about the result and therefore, individually, feel as unconcerned about it as if nothing more than a review was to take place,” he wrote. Visiting Pittsburg Landing one final time on April 4th, Grant felt assured that all was calm. While returning to his headquarters eight miles away in a rainstorm, Grant’s horse fell on his leg, badly injuring his ankle. Finally, after writing cautionary orders and learning about increased skirmishing on April 5th, Grant confidently wrote that "the main force of the enemy is at Corinth."

American Battlefield Trust

Other historians have jumped into the debate. In "The Battle of Shiloh Surprise in Tennessee," Wiley Sword compared Shiloh to the Japanese surprise attack on Pearl Harbor. “Despite occasional fire from the pickets in the adjacent woods, and a brief skirmish on April 4th in the outlying timber, the Union army was at ease,” remarked Sword. William McFeely stated, "on April 5, 1862, the huge [Confederate] force was just south of Sherman's position and so clamorously noisy that they lost hope that their attack could be a surprise . . . They were wrong. But not because none of the Federal soldiers noticed them—indeed, there was a skirmish on April 5." Brooks Simpson asserts that Grant “did not believe an attack was imminent, and the intelligence offered by [General] Sherman suggested little cause for concern.” Ron Chernow states that "the charge of being blindsided at Shiloh would long be a sore point with Grant. Ordinarily the soul of honesty, he sought to rewrite history, claiming to have known a major battle was imminent. Unfortunately, his April 5 correspondence makes crystal clear that he had no intimation of a massive attack in the offing. He dismissed raids on Union outposts as the work of reconnaissance forces."

In the end, the evidence suggests that Grant was surprised by the Confederate attack on April 6th and that he was overly confident about his forces’ ability to quickly defeat the enemy. The Northern public had been clamoring to an early end of the war, but the bloody results of Shiloh served as a warning that the Civil War would be anything but short. "I gave up all idea of saving the Union except by complete conquest,” Grant remarked in his memoirs. Despite the criticism, Grant left Shiloh with his job and the support of President Lincoln. But the horrific experience nevertheless pushed Grant to evolve his thinking of military strategy towards a "Total War" concept.