Last updated: October 17, 2023

Article

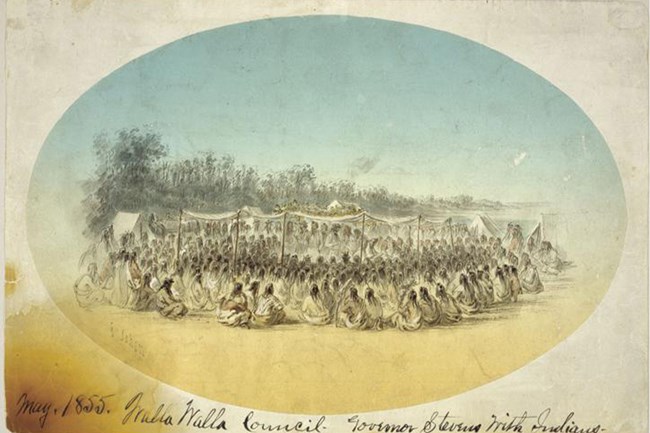

Walla Walla Council (1855)

PUBLIC DOMAIN

Article written by James Schroeder

On May 29, 1855, 5,000 Native American chiefs and tribal delegates to the Walla Walla Treaty Conference gathered on the grasslands near Walla Walla to meet with Washington Territory’s Governor Isaac Stevens and Oregon Territory’s Superintendent of Indian Affairs Joel Palmer to negotiate tribal boundaries in eastern Washington. An afternoon rainstorm foreboded turbulent times ahead. After convening for two weeks, tribal representatives agreed to cede 60,000 square miles (155399 sq km) to the United States government in exchange for the Yakama Reservation in Washington, the Umatilla Reservation in Oregon, and the Nez Perce Reservation in Idaho. These concessions opened land to White settlement in the Priest Rapids Valley and profoundly reshaped the political geography of Washington.

During the nineteenth century, many Whites adhered to the ideology of manifest destiny calling for divinely sanctioned continental expansion. Governor Stevens was no different. In 1853 after President Franklin Pierce appointed him both Governor and Superintendent of Indian Affairs in the newly created Washington Territory, Stevens promptly used his authority and his military surveying experience to promote White settlement and railroad networks in the Pacific Northwest, aided by army surveyor Captain George McClellan who later rose in fame as Union Commander during the American Civil War. Stevens believed that before his plans could come to fruition he needed to legally abolish Native claims to the land.

Between 1854 and 1855 Stevens pressured Puget Sound tribes into signing treaties that confined them to reservations while ceding much of the west coast to the United States. He pushed tribes to exchange traditional migratory lifestyles for European-style farming, and like many Whites saw reservations as a temporary step to assimilate Native Americans into “civilized” society. In mid-1855 Stevens and Palmer approached tribes of the Columbia Basin hoping to achieve similar concessions. Leaders from the Yakama, Umatilla, Cayuse, Walla Walla, Nez Perce, and associated tribes traveled to Walla Walla to listen to their proposals.

Yakama Chief Kamiakin initially tried to unite other leaders in opposition to any exploitative treaties. Stevens and Palmer undermined this unity by cajoling and threatening the delegates. Stevens emphasized the benefits of farming, claimed the United States would make generous payments in clothing and equipment, and warned that reservations provided protection against “bad white men.” Palmer declared that Native Americans and Whites could never live together in harmony, disingenuously warning that without reservations and special protections, tribes would suffer theft and abuse at the hands of settlers. Interpreter Andrew Pambrun claimed Stevens also told Kamiakin “if you do not accept the terms offered… you will walk in blood knee deep.” Gold had also been recently discovered in northern Washington, and few Tribal leaders could safely ignore the genocidal fate suffered by thousands of Native Americans during the California gold rush of 1849.

Faced with these dire choices, Tribal leaders felt they had little choice but to agree to Stevens’ terms. Stevens did make limited concessions. Tribes retained the right to fish and hunt on ceded lands, practices vital for physical and spiritual sustenance. In addition, although Stevens only proposed the Yakama and Nez Perce reservations, Tribal representatives successfully demanded a third reservation for the Umatilla, Walla Walla, and Cayuse tribes. On June 9 delegates signed the Yakama Nation Treaty of 1855 and the Walla Walla, Cayuse, and Umatilla Treaty of 1855. According to Pambrun, when Kamiakin signed “he was in such a rage that he bit his lips that they bled profusely. A treaty with the Nez Perce was signed two days later.

Stevens achieved the land concessions he desired, but his domineering attitude laid the foundation for future conflict. He conveniently overlooked the fact decentralized tribal leadership precluded any single chief from speaking for the entire tribe. Many groups impacted by the treaties of 1855 were not even represented at the council. Stevens added to Native grievances by allowing White settlement in ceded territory before the treaties were ratified by Congress and resulting skirmishes with miners only escalated tensions. The death of Indian Agent A. J. Bolon in September 1855 at the hands of Yakama warriors angry over the murder of a Tribal family started the Yakama War, a period of hostility lasting until 1858. Skirmishes erupted across Washington as the United States Army and territorial volunteers clashed with Yakama warriors supported by tribes throughout the Columbia Basin. In 1856 a young Cornelius Hanford, founding father of the town of Hanford, took refuge in the Seattle blockhouse when tribes attacked the community.

There were few hostilities in the vicinity of White Bluffs, but the Priest Rapids Valley provided a useful trade and travel route for soldiers and civilians throughout this period. The Army forbade White settlement in eastern Washington due to the potential danger but lifted these restrictions after 1858. In 1859, Congress finally ratified the Walla Walla Conference treaties, marking a traumatic period of displacement for many Native American. There were a few exceptions, however. Arguing they had never signed a treaty with the United States, the Wanapum Tribe quietly remained in the Priest Rapids Valley where they had resided since time immemorial. In the early 1940s the Army temporarily allowed Wanapum members to continue accessing traditional fishing grounds on the restricted Hanford Site.

The rights and stipulations enumerated in the treaties of 1855 still impact local tribes. Fishing and hunting on ceded land remain cherished rights. These treaties also codified arbitrary boundaries drawn by United States officials when delineating tribal identities. The Yakama Treaty confederated fourteen disparate tribal bands into the Yakama Nation while the Walla Walla, Cayuse, and Umatilla Treaty placed three separate tribes onto one reservation, laying the foundations for contemporary Tribal political identities in the Columbia Basin.

- Parker, Martha Berry. Tales of Richland, White Bluffs & Hanford, 1805-1943, before the Atomic Reserve. Fairfield, Wash: Ye Galleon Press, 1986.

- "Pre-1943 Oral Histories", Hanford History Project, http://hanfordhistory.com/collections/show/1

- Bauman, Robert, and Robert Franklin. Nowhere to Remember : Hanford, White Bluffs, and Richland to 1943. Edited by Robert Bauman and Robert Franklin. Pullman, Washington: Washington State University Press, 2018.

- Hanford-White Bluffs Pioneer Association, “Harry and Juanita Anderson Collection (Hanford-White Bluffs Pioneer Association),” Hanford History Project, accessed March 23, 2023, http://hanfordhistory.com/items/show/4939.

- Hanford-White Bluffs Family Histories, Hanford History Project, http://hanfordhistory.com/collections/show/6