Last updated: September 23, 2020

Article

Voting by Mail During a National Crisis

Library of Congress

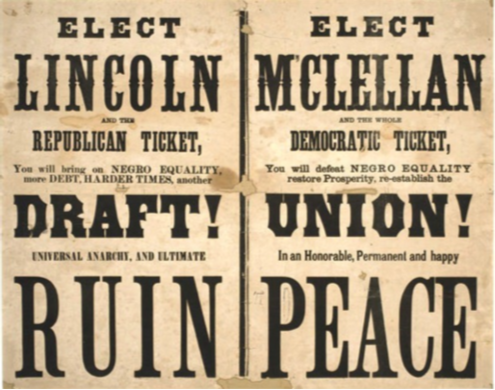

Less than a year after the commander in chief issued the contentious Emancipation Proclamation, with over half a million eligible voters temporarily assigned hundreds of miles away from their homes, and in the middle of a cataclysmic war for the very soul of the nation, Americans asked themselves a key question: how do we maintain our democracy? One of the central characteristics of a representative democracy is the ability of its citizens to cast a vote for their national leaders in a free and fair election. As President Lincoln’s first term drew to a close, the war was not yet settled, nor were the chasms of political division within the Republican Party. The situation was made all the more complex by the fact that many registered voters who presumably would vote for the reelection of their current commander in chief were unable to return home to cast their ballots.

The problem of voting in the 1864 election had occurred to a number of state legislators in the early days of the Civil War. The difficulty with voting in the 1862 mid-terms had given them a glimpse of the difficulties they would have during the election for the next president, so a number of states acted quickly to set in place a mechanism by which soldiers in the field could vote by mail. At the onset of the Civil War, the only state constitution with a provision for mail-in voting by men away in military service was Pennsylvania. This was a throwback to difficulties made apparent during the War of 1812. Minnesota and Wisconsin were quick to revise their state constitutions to allow mail-in voting in the fall of 1862. Ohio, Vermont, and West Virginia amended their state constitutions in 1863, and a number of other states just barely made or missed the 1864 election.

State constitutional amendments made during the Civil War generally fit the same pattern as those of Wisconsin and Minnesota. They specified 1) that all eligible voters “shall be entitled to exercise the right of suffrage at any general election” wherever they were stationed, 2) that “elections at the camps should be in the manner consistent with the general election laws of the state,” and 3) that officers of the regiments should oversee the process and appoint inspectors.

Library pf Congress

Soldiers would fill out their ballots by hand and seal them in an envelope which would then be sealed with wax and sent by mail to their respective voting districts. Some states had provisions that required the ballots not to be opened until the day of the election, while others indicated that the votes not be marked in any way as to make them discernable from those votes cast at home.

The State of Ohio recorded 470,722 votes cast by Ohioans at their home precincts and an additional 50,903 votes cast by Ohio soldiers in the field. Votes cast by Ohioans at home for Lincoln numbered 265,154 (a relatively slim majority to McClellan’s 205,568), but Ohio soldiers voted 41,146 for Lincoln and a scant 9,737 for McClellan.

Despite warnings and accusations of potential fraud in the soldier vote, only one case of voter fraud was brought to trial, and it involved several New Yorkers who attempted to record the votes of recently deceased and incapacitated New York soldiers in order to swing the “Soldier Vote” for McClellan. The anomaly was caught, and glaringly obvious, when the results of one district which had raised an entire regiment of soldiers saw their results did not match those of any other districts. The fraudulent report there had McClellan winning over 90% of the vote rather than losing almost three to one as was the case in nearly every other district.

The American Civil War was not the last time a President was elected during a national crisis with eligible voters far from home; indeed the election of 1944 during the height of American involvement in World War II was just as chaotic with a much larger force of voters mobilized around the world, but the events of the 1864 election set a firm precedent that no matter where Americans are, no matter what they have been called upon to endure, and no matter how big their project may be, they are still Americans and they still value one of the core tenets of American democracy – participation in a free and fair election to choose their elected officials and their commander in chief.