Last updated: February 5, 2021

Article

Volunteers Find Fewer Than 2,000 Monarchs Overwintering in California in 2020

© The Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation 2021

January 2021 - Each fall, western monarch butterflies migrate to the California coast, to protected groves where they huddle together and wait out the cold. This fall, as the monarchs settled into their winter homes, observers noticed fewer monarchs. A lot fewer monarchs.

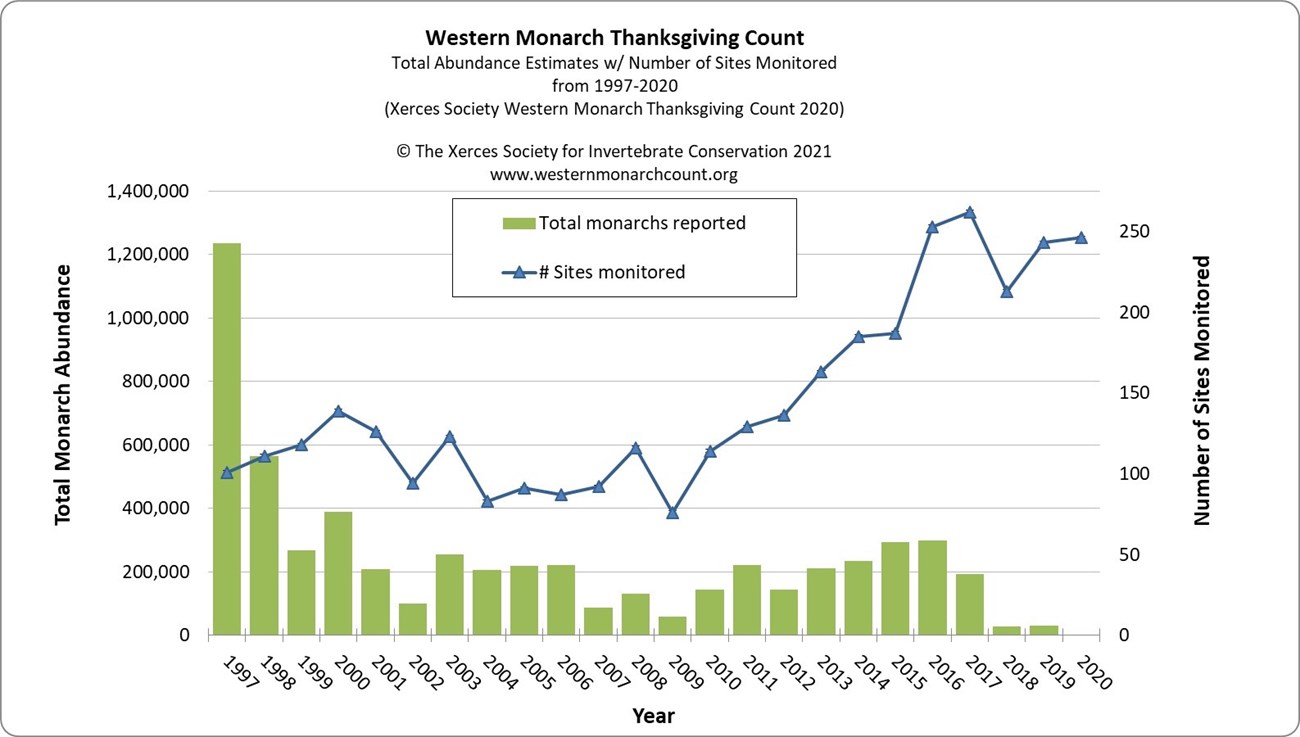

Data from the volunteer-driven Western Monarch Thanksgiving Count indicate less than 2,000 western monarchs overwintering in California in 2020. This represents a devastating decline of more than 99.9% of their 1980s population. Then, upwards of 4.5 million monarchs made the annual migration to the Pacific coast. In other words, in less than a human lifetime, the number of western monarchs went from the current population of Los Angeles to the number of students at a single suburban high school. Counts in Marin County also reflect this drastic decline. Where there were tens of thousands of monarchs as recently as 2015, volunteers found fewer than 200 in 2020.

This data came out just as the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) decided not to list the monarch butterfly as a federally endangered species. While they “found the monarch meets listing criteria under the Endangered Species Act,” they are focusing resources “on our higher-priority listing actions,” said USFWS director Aurelia Skipwith in a press release. The decision follows a recent ruling by the California Superior Court, which determined that insects are excluded from protection by the California Endangered Species Act.

© Morgan Stickrod / Photo 28030956 / 2018-11 / iNaturalist.org / CC BY-NC

All this means that the western monarch population is plummeting towards extinction without state or federal protective measures. However, for Mia Monroe, volunteer monarch monitor of 40 years and Marin Community Liaison for Golden Gate National Recreation Area, the power of community science, advocacy, and activism offers a beacon of hope. “When the monarch was proposed for listing in 2014, people didn’t wait for the listing. Studies started, plantings of milkweed are underway, protection of habitat started, conservation groups made monarchs a focus throughout the whole continent,” said Monroe.

No singular factor is traceable to the monarch’s decline. Instead, a combination of destruction and degradation of overwintering, egg-laying, and nectar sites, along with pesticides and climate change, are all likely contributors.The Xerces Society’s Western Monarch Call To Action is full of resources individuals and land managers can use to help protect and save the monarchs.

For now, the question remains; after the monarchs disperse in the spring, how many will return next winter?

“I tend to be a hopeful person because that’s what monarchs do, they give you hope. You want wild, beautiful things like that to be part of your everyday life,” says Monroe. “But I also feel desperately dismal. I’ve witnessed deep decline. I wonder what’s next.”

For more information

-

Explore the West Marin Environmental Action Committee’s Marin’s Monarch Movement report

- Participate in future Western Monarch Counts

- Find more ways to help from the Western Monarch Call to Action

- Learn about the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service listing decision

- Contact Golden Gate NRA Marin Community Liaison and Western Monarch Count Regional Coordinator Mia Monroe