Last updated: October 10, 2024

Article

The Evolution of Virginia Agriculture on the Portici Cultural Landscape

NPS/Jones 2021

This article was adapted from the Cultural Landscape Inventory documentation on Portici, Manassas National Battlefield Park, prepared by Angelina Riberio Jones in 2022.

Within the boundary of Manassas National Battlefield Park, Portici Plantation has been a fixture in the landscape since 1820, and it was preceded by an earlier plantation on the same property from around 1733. Portici is a historic landscape that demonstrates the development of historic agriculture in Virginia since European contact and up to the present day.

The earliest evidence of agriculture in Virginia is associated with Indigenous Algonquin and Siouan speaking people who periodically performed controlled burns to clear land for cultivation. Though people have occupied present-day Virginia since the Paleoindian period (11,000 to 9,000 BCE), widespread agriculture was not practiced until the Late Woodland period (1000 to 1600 CE). After European colonizers arrived, the agriculture industry continued to dominate the economy in much of rural Virginia, including what is known today as Prince William County where Manassas National Battlefield Park is located.

Early European Agriculture in Virginia

Prior to the establishment of the Portici Plantation, agriculture had become an important industry for European colonists throughout the Northern Neck of Virginia. During the colonial period land tenants cultivated most of the land, managed through lease agreements with the land holders.

After colonists and the Iroquois Nation signed the Treaty of Albany in 1722, the population of European settlers in the Virginia Piedmont region began to swell. Tobacco cultivation quickly became the primary source of wealth for colonial planters in the Northern Neck, fueling colonial development in the area. Colonists also supplemented their cash crops with produce, livestock, and timber woodlots.

Indentured servants in Virginia and throughout the colonies were primarily born in the British Isles and had entered a contract to sell labor for a pre-determined period of time. This contractual agreement was often legally coerced and targeted debtors, felons, or other vulnerable populations. However, there were also people who voluntarily agreed to enter the indenture. These indentures also held the promise of freedom at the end of the contract, though the contracts could be extended as part of a sentenced punishment.

Despite this disenfranchisement, enslaved people continued to express personal agency and maintain connections to their African cultural heritage. Traditions and materials evolved and were passed down to later generations born in the United States. For example, there is evidence that enslaved people at Portici in the mid-19th century, the majority of whom would have been born in North America, played a game of Egyptian origin called “mancala.” Additionally, enslaved people would often create gardens and grow food to supplement the insufficient rations provided by enslavers. Any surplus from these gardens were occasionally used to barter with or trade between other enslaved people within their plantations and neighboring ones. This created an inter-plantation microeconomy that was managed and organized by enslaved people exclusively. This income was able to be used by a small number of enslaved individuals for the purchase of manumission, granting them legal freedom in colonial Virginia.

NPS/Jones 2021

Development of the Portici Plantation

The Portici Plantation was preceded by another plantation on the same property, known as the Pohoke Plantation. The origins of the name are unknown, but the Pohoke refers to a dwelling built on the property by a tenant farmer sometime around 1733. Tenant farmers rented the property and house until Spencer Ball (1762-1832) and his wife Elizabeth “Betty” Landon Carter Ball (1768-1842) occupied it in 1802. Betty Ball was the sister of the landowner, George Carter (1777-1846), and descendant of the Carter family who had maintained land holdings over the area since the 1650s.After building their first plantation in the area sometime around 1653, members of the Carter family had acquired extensive land rights encompassing the Great (Upper), Middle, and Lower Bull Run Tracts of the Northern Neck, and members of this family had granted leases to the tenants on the Pohoke Plantation. Portici was built in the Lower Tract which had been passed on to two generations of Carter heirs and subsequently atomized before reaching the hands of George Carter.

Figure from McGarry, “Manassas Historic Sites Survey: Manassas National Battlefield Park, Virginia,” 1982. (NPS Electronic Technical Information Center (eTIC) https://pubs.etic.nps.gov/, accessed 2021).

In addition to a large house for the plantation owner’s family, plantation landscapes held dwellings for the enslaved laborers which were typically located away from the main house. Although those quarters were present on Portici, it is likely that some of the enslaved people resided in the main building’s cellar as well. Compared to the main house, the enslaved quarters were built to be more temporary structures, likely as a means for enslavers to further highlight the social divide they were facilitating.

Forbes, Edwin. "Slave cabin near Warrenton, Va." 1963 Aug. 5. (Library of Congress, https://lccn.loc.gov/2004661591, accessed 2024).

Alfred Ball and Changing Agricultural Methods

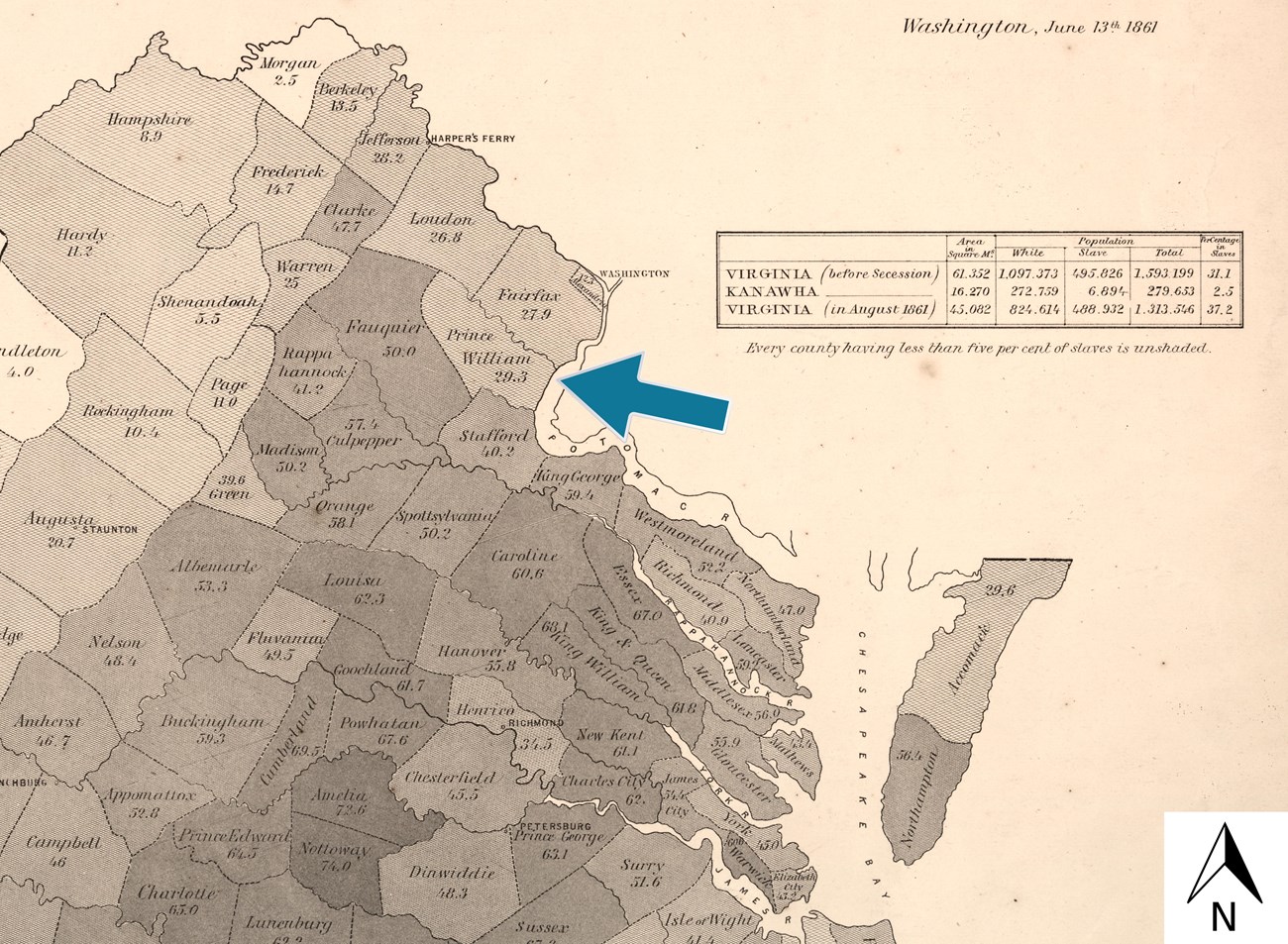

When Spencer Ball died in 1832, he left the Portici plantation to his wife and willed ownership of several people he had enslaved to his six children. Of those, his will directly names Robert “son of Aggy”, Armistead, Sukey “daughter of Chloe” and her child, Maria “Sally’s daughter” and her child, Polly and her children (Prince William County Circuit Court 1832: WB N, p. 426). Spencer and Betty Ball’s only surviving son, Alfred, inherited the property after Betty passed away in 1842.During both Alfred and his parents’ management of Portici, the population of the Commonwealth of Virginia had been declining. After the international importation of enslaved people was banned in 1808, a domestic slave trade economy developed. Enslavers in and around Virginia started to sell the people they enslaved to southern Gulf States which had a growing agricultural industry. During the Ball family’s management of Portici, the population of enslaved people in Virginia went from just over 40 percent of the population to just under 30 percent.

Graham, H. S, and E Hergesheimer. "Map of Virginia: showing the distribution of its slave population from the census of 1860," 1861. (Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/2010586922/, accessed 2024).

The declining soil qualities shifted the primary staple crop from tobacco to less labor-intensive crops like grains. This allowed for enslaved people to develop professional skills outside of cultivation. Tending to draft animals, smithing, and construction were some of the more frequent specializations. Enslaved women on the Portici plantation often spun wool or flax and crafted garments for the Ball family and other enslaved laborers. Enslaved people on Portici also engaged in crafts related to leather tanning, carpentry, and maintaining an apiary.

The Civil War and Portici

Francis “Frank” Waring Lewis (1822-1913), the nephew of Alfred Ball, owned Portici by the time of the Civil War. Frank Lewis continued to operate the plantation similarly to Alfred Ball, growing mostly the same crops and using enslaved labor. With the outbreak of the Civil War, the landscape surrounding Portici became a clear area for potential conflict.

“Draft General Management Plan, Environmental Impact Statement,” 2005. (NPS Electronic Technical Information Center (eTIC), https://pubs.etic.nps.gov/, accessed 2021).

After receiving a warning from Confederate forces that a battle would break out, Frank Lewis fled the Portici plantation, taking himself and his family to the “Snow Hill” plantation where his wife, Frances “Fannie” Adeline Stuart (1828-1899), had been raised. The Lewis family left behind 11 people that they enslaved, expecting them to continue managing and looking after the plantation in their absence.

They took most of the furniture they could transport to Snow Hill and stored valuables with their neighbor James Robinson (1799-1875). Robinson was a free Black man who owned the neighboring farm, he is also thought to be a biological member of the Carter family giving him familial ties to the Lewis’s.

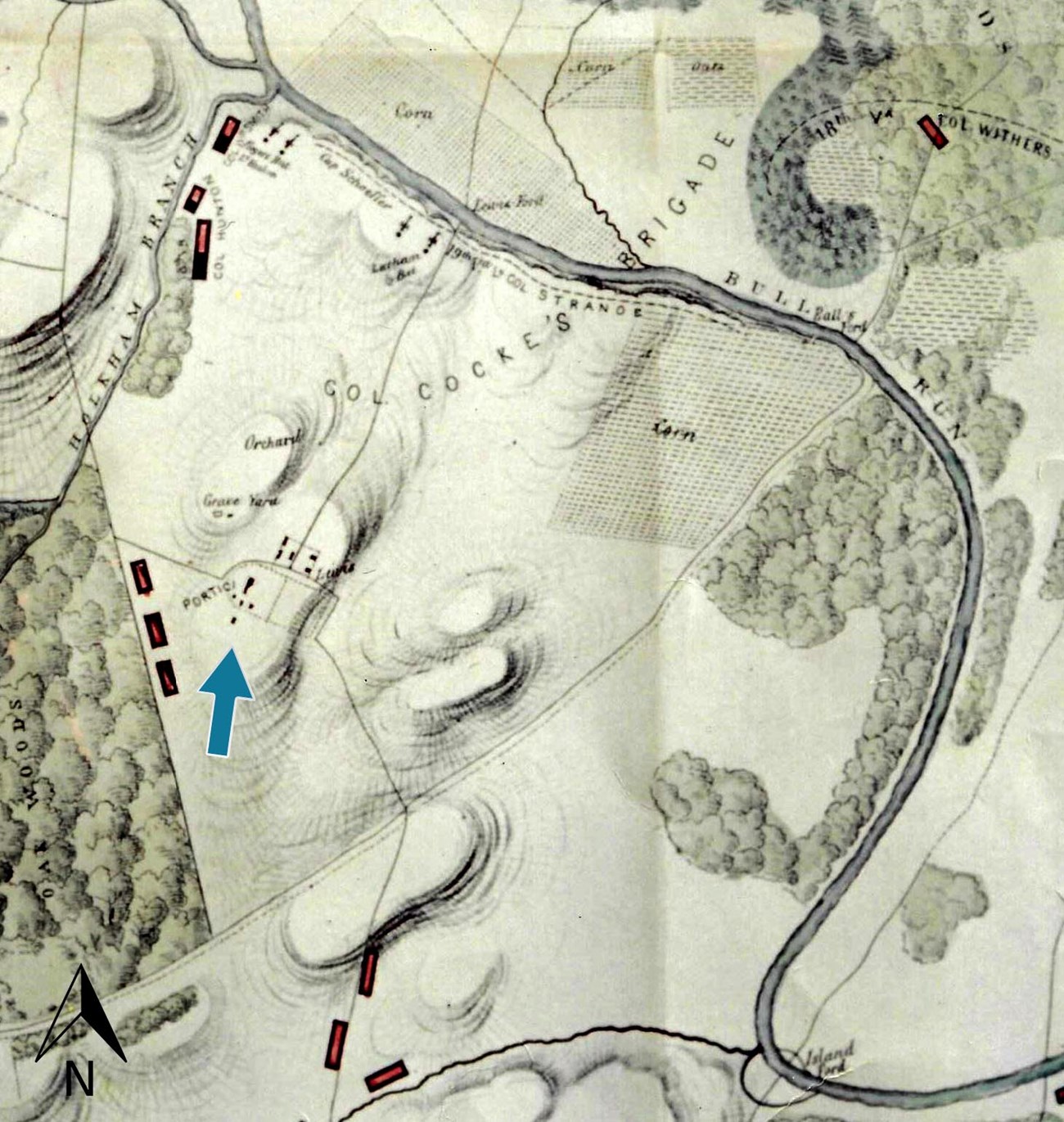

“Map of the Battle Ground of Manassas from Actual Surveys by an Officer of General Beauregard's Staff Showing the Exact Position Occupied by Federal & Rebel Forces in the Battle of 21st July 1861,” 1861. NPS/Manassas National Battlefield Park Archives.

The Second Battle of Manassas broke out on August 28, 1862, and mostly took place outside of the Portici cultural landscape. Although contradicting oral histories blur the exact date, the Portici main house burned down sometime after this battle and before the end of the war. The surrounding landscape and neighboring farms were severely damaged from both the fighting and neglect during the war.

Reconstruction and Beyond

The Lewis family returned to Portici in 1865 and rebuilt the main house on the same ridge as the earlier building. With the emancipation of the formerly enslaved population, the agriculture industry in Virginia was transformed. Production on the Portici farm was scaled down, with Frank Lewis selling off portions of his property over the following decades. This was a common trend throughout Manassas as smaller farms began to replace the larger plantations which had been built by enslaved labor.

“Photographs taken at the maneuvers near Manassas, Va., September 1904,” 1904. (Library of Congress, https://lccn.loc.gov/2005687979, accessed 2021).

Frank Lewis managed the Portici farm until his death in 1913, after which time the Portici farm was divided between his four children. The Portici cultural landscape was subsequently farmed by members of the Lewis family until Frank Lewis’s granddaughter Fannie Tasker Lewis Lee (1852-1931) sold her portion of the land to Carol Homola Aldrich (1914-2007) and her husband in 1947. Frank Lewis’s grandson, Robert Lee Lewis, Jr. (1893-1983), later sold his portion of the Portici farm to a man named William Henry Wheeler (1911-1980) in 1950, marking the final descendant of the Carter family to manage the land. Wheeler, in tandem with a business partner named Thomas Pearson, ran a successful dairy farm on the land following a trend towards dairy production across Prince William County.

“Fannie Lee Henry House MNBP,” 1941. NPS/Manassas National Military Park Archives.

“Aerial Photography,” 1980. Fairfax County Government.

Eventually the National Park Service (NPS) acquired tracts from both the Aldrich family and Wheeler as the boundaries of Manassas National Battlefield Park expanded. Upon acquisition of the properties, part of the Portici cultural landscape was under lease to a turf company who maintained sod harvesting rights until 1996. As recently as 2021, NPS entered a 10-year agricultural lease on 117 acres of what used to be the Portici farm for the production and harvesting of hay, continuing the long-standing agricultural legacy on the land.

NPS/Jones 2021

Quick Facts

-

Cultural Landscape Type: Historic Vernacular Landscape, Historic Site

-

National Register Significance Level: National

-

National Register Criteria: A, D

A - Military use during the Civil War.

A - Commemorating and memorializing the First and Second Battles of Manassas.

A - An example of a Virginia Piedmont plantation prior to the Civil War and a farm following the conflict.

D - For its potential to yield archeological data pertaining to Virginia Northern Piedmont agricultural practices and social history and the Civil War..

-

Periods of Significance: 1861-1865, 1733-1936, 1936-1944

Landscape Links

-

National Register of Historic Places: Manassas National Battlefield Park

- Plan a Visit: Tour Stop #11

The original documentation this information was gathered from was heavily informed by the work compiled in the archeological report entitled Portici: Portrait of a Middling Plantation in Piedmont Virginia (1990) prepared by Kathleen A. Parker and Jacqueline L. Hernigle; Coming to Manassas: Peace, War, and the Making of a Virginia Community (2003) prepared by Linda Sargent Wood and Richard Rabinowitz; and Archeological Overview and Assessment Manassas National Battlefield Pre-Draft (2018) prepared by John Bedell and Kisa Hooks.

Fairfax County Government, Google Earth

Image Descriptions

1937 aerial

This image shows the condition of the farm at a point of atomization of Lewis family ownership and the formation of the Recreational Demonstration Area (RDA).

“Aerial Photography,” 1937. Fairfax County Government (https://www.fairfaxcounty.gov/maps/aerial-photography, accessed 2021).

1953 aerial

This image shows the transition of a portion of the property to dairy farming under Wheeler's ownership.

“Aerial Photography,” 1953. Fairfax County Government (https://www.fairfaxcounty.gov/maps/aerial-photography, accessed 2021).

2024 aerial

While there are fewer fields in cultivation than there once were, landscape features still convey the agricultural character of the property and its historic importance in the area's economy and during the Civil War. The continued agricultural use of the landscape is integral to understanding Portici's connection to the history of Virginia Piedmont land cultivation.

GoogleEarth (accessed 2024).

For a more detailed view of the landscape's development, annotated maps in the Portici Cultural Landscape Inventory report show changing ownership and use and identify resources within the landscape boundary and in Manassas National Battlefield Park.