Part of a series of articles titled The Midden - Great Basin National Park: Vol. 17, No. 2, Winter 2017.

Article

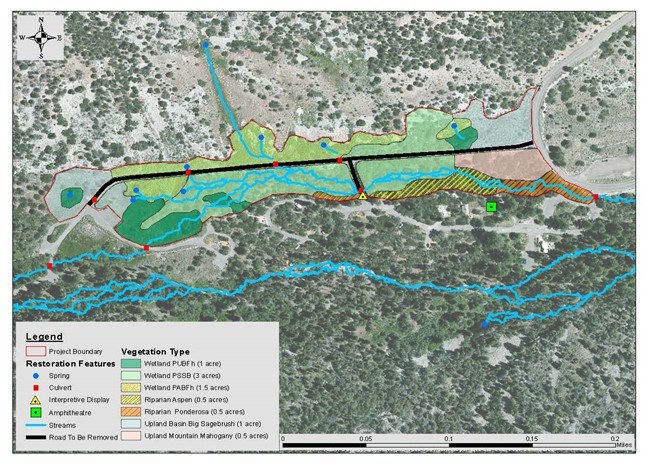

Upper Lehman Wetlands Restoration

This article was originally published in The Midden – Great Basin National Park: Vol. 17, No. 2 , Winter 2017.

The Upper Lehman Campground was developed in the 1960s by the U.S. Forest Service. The area of the northern campground access road was originally a wetland complex consisting of springs, seeps, wet meadows, and a braided riparian stream system. A road was graded in, covered with several feet of road base, and then paved. To redirect water from both the road and nearby campsites, ditches were constructed to drain wet areas and channel water through five culverts. A perennial tributary was placed in a 20 meter long ditch and diverted into the main steam of Lehman Creek.

The existing conditions showed that wetland functions and values were compromised. Wetland function was eliminated or degraded, native vegetation was reduced, and hydrologic function was impacted due to the diversion of natural flow patterns. Loss of hydrologic function was by far the largest impact. Wetlands and riparian habitat are extremely limited within the park, but because of their outsized ecological footprint, are typically valued more than other ecological systems.

NPS Photo

-Restore one-half mile of riparian stream habitat to proper functioning condition

-Restore eight acres of wetland habitat to proper functioning condition

-Decommission one-third mile of road and restore native ecosystems

-Monitor biological communities to document restoration success.

All wetland and riparian types showed evidence of adverse impacts due to channelization and loss of water. There are seven mapped ecological systems within the project area. Five of these will benefit from the project:

NPS Photo

• Wetland Type PSSB is a palustrine system dominated by woody vegetation, (aspen, Wood’s rose, and water birch) that are small or stunted because of environmental conditions.

• Wetland Type PABFh is a palustrine system but is dominated by sedges and emergents that grow principally on or below the surface of the water for most of the growing season. It is semi-permanently flooded system with surface water persisting throughout the growing season.

• Riparian Aspen is dominated by quaking aspen with greater than 60% cover in unconsolidated sediments near permanent water. White fir may be present in the over story but the understory is dominated by wetland grasses, sedges, and forbs.

NPS Photo

Wildlife: The species below depend upon wetlands and riparian stream habitat, are species of management concern, and were documented within the project area. All of the species would benefit from larger and proper functioning wetland and riparian habitats.

• Water shrew (Sorex palustris)

• Inyo shrew (Sorex tennellus)

• Ermine (Mustela erminea)

• Long-tailed weasel (Mustela frenata)

• Yellow-bellied marmot (Marmota flaviventris)

• MacGillivray’s warbler (Oporornis tolmiei)

• Yellow warbler (Dendroica petechia)

NPS Photo

Last updated: March 6, 2024