Last updated: February 9, 2023

Article

Under the Floorboards: Preserving Newspapers from 1927

Emma Rockenbeck

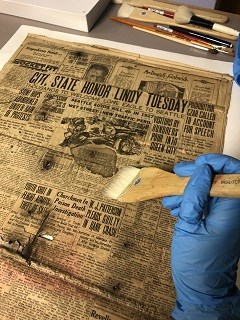

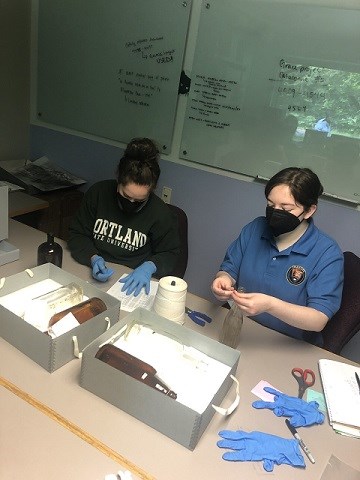

The newspaper sections that I was processing were mostly from The Seattle Daily Times, Sunday, September 11, 1927. They were found beneath the floorboards of the Paradise Visitor Center during the Paradise Developed Area Dig (Paradise Dig), a multiyear archaeology project led by the archaeology team at Mount Rainier National Park (MORA). After being decontaminated of potential hantavirus for a year in a freezer, the finds of the Paradise Dig were brought by the archaeology team to the Mount Rainier Curatorial Facilities to be housed in their archives. This June, I worked alongside Northwest Youth Corps (NYC) Fellow Audrey Nelson, Archaeology Student Intern Grace Atkins, MORA Curator Brooke Childrey, and a group of dedicated volunteers to process the finds of the Paradise Dig. The newspapers found under the floorboards had been used as insulation between the baseboard and the flooring. Given their history, they were in remarkably good shape.

The September 11, 1927 edition of the Seattle Times was full of illustrated full-page advertisements for tools, farming equipment, wagons, cars, real estate companies, and shipping companies. The Society section was dedicated to gossip about rich and influential Seattle area families. To my modern eyes, this section read like a posh version of an early 2000s tabloid magazine – full of details that hardly seemed factual and plenty of pearl-clutching. The fashion section had an advertisement for “Gay Tub Frocks to Buy This Fall", accompanied by charming illustrations of dresses, hats, and fur coats. I have always loved fashion history. When I imagine what a person in the past wore – what materials were used, how the garment was fastened, how it must have felt on their body – I briefly step into their life experience.

Emma Rockenbeck

It was also facinating to see the news headlines from September 1927. Some jumped out to me as a modern reader – headlines about prohibition, an article that raves about modern imitation leather on automobiles deceiving even the experts, and articles that call Seattle Queen City (you are more likely to hear Seattle referred to as Jet City or Emerald City these days). Other headlines seemed more familiar – sensationalist takes on local crimes and murders, traffic safety reforms, political posturing, and melodramatic moaning about “what society has come to.”

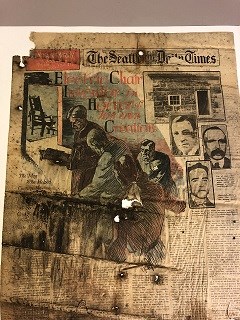

The page that surprised me most was the front page of the issue. It had a combination of illustrations and photographs that looked like the cover of a 1950s science fiction book. In the center is an illustration of four men, sketched with dark noir style shadows and colored with splashes of a vivid, sickly green. The men appear to be two prison guards, a convict in a prison jumpsuit, and a priest in a long dark robe reading the prisoner his last rights. In the left corner of the illustration looms an electric chair, waiting to claim the prisoner’s life. Bold red letters proclaim, “Electric Chair Inventor in Horror of his own Creation.” In the right corner of the page are three photographs. The first is of Alfred Porter Southwick, the inventor of the electric chair. The second and third photographs are of two prisoners. A caption reads “No more spectacular battle was ever fought to save Bartolomeo Vanzetti (center right) and Nicola Sacco (center) from the death chair.” The front-page story of this issue was the Sacco and Vanzetti case.

Emma Rockenbeck

It was jarring to find such a controversial piece of history in the form of a newspaper. This piece of crumbling paper in my hand was once an ordinary object that the builders of the Paradise Visitor Center thought nothing of, stuffing it under the floorboards as insulation. After all, we still use newspapers in a similar manner; we wrap objects in newspaper when we move, we lay newspaper down under art projects to keep paint from staining our tables, and we wrap packages in newspaper. Future generations may find newspapers from 2023, stuffed inside a box in some attic, and be equally as intrigued with the headlines.

I often wonder what future generations will think of our contemporary news media. News media is us writing history as we go; shaping the events of our world into a tidy narrative, trying to make all the frustration, pain, uncertainty, fear, and joy of life understandable on a human scale. That is what humans do – we tell stories. Only time will tell if these stories match with the reality we are living. This is why it is important that we try to preserve both historic artifacts and contemporary artifacts with cultural significance, and then study that history and learn what we can.

Article written by Emma Rockenbeck

for "A Day in the Life of a Fellow" Article Series

National Park Service - Workforce Management Fellow

in Partnership with Northwest Youth Corps