Last updated: August 15, 2023

Article

Uncovering Franklin Court

NPS photo

Franklin Court

Benjamin Franklin lived in a brick house on this site while serving in the Continental Congress and the Constitutional Convention. Franklin died here in 1790 and the house was torn down 22 years later. Today the site contains a steel "ghost structure" outlining the area where Franklin's house stood.

The Development of Franklin Court

After decades as renters, Benjamin and Deborah Franklin built a house for themselves on land behind their Market Street properties. Having arranged with master carpenter Robert Smith to build the house in the quiet garden courtyard, Benjamin Franklin sailed for London and entrusted his wife with managing the details of building and furnishing the house. His letters to her often included specific instructions about the work that needed to be done. Look for excerpts from their letters on the viewing portals and pavers throughout the outdoor exhibit.

The Franklins never lived in the home together. Deborah Franklin lived in the house with their daughter Sally (Sarah), son-in-law Richard Bache and their children until her death in 1774. Sally Bache and her family continued to live in the house with Benjamin Franklin after his final return to Philadelphia in 1785.

Benjamin Franklin made major improvements to the property in the five years before his death. He built a printing shop, bindery, and foundry for his grandson, Benjamin Franklin Bache. He added a new wing that included a large dining room, library, and additional bedrooms. He also built three rental properties on Market Street, two of which flanked an arched carriageway into his courtyard.

NPS Photo

Franklin's Heirs Transform the Property

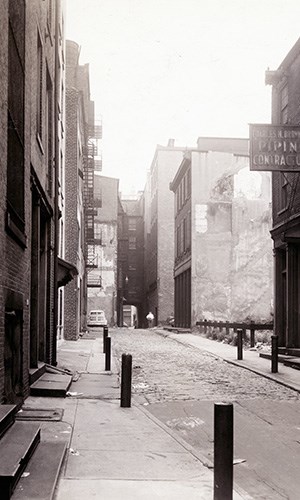

After Benjamin Franklin's death in 1790, the Baches inherited the house, but they took to living outside the city and traveling to England. Starting in 1794, they rented the house, most notably to the Chevalier de Friere, the Portuguese minister. Next, it became a boarding house, then an academy, later a coffee house, and finally, a hotel. Sally Bache returned to die in her home in 1808. Richard stayed on after her death and shared the house with the African Free School until his death in 1811.By 1812, the land had so increased in value that the Bache heirs tore down the house and rebuilt Franklin Court with rental row houses. The new buildings faced a narrow street that ran the length of the block from Market Street to Chestnut Street. Known as Orianna Street, it was soon crowded with shops—silversmiths, bookbinders, printers, bakers, and shoemakers.

The only physical remains of Franklin's once grand courtyard and home are the arched carriageway he added as entry to his property, a portion of the cellar kitchen, several foundation walls, and a privy pit.

NPS Photos

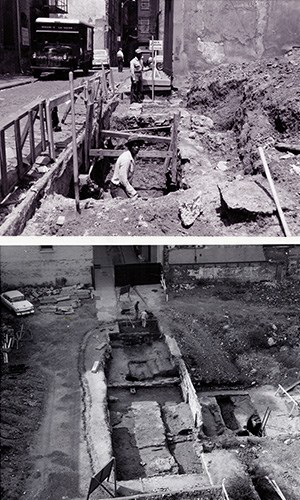

Digging in at Franklin Court

In 1948, Congress created Independence National Historical Park, which included Franklin Court. After the National Park Service began investigating the courtyard, archeologists located the outline and basement feature of the Franklin's house. In 1972, experts met to decide whether to reconstruct the house in preparation for the bicentennial of American independence. As evidence of the building's original design was incomplete, they decided to create a representational design.The first archeological excavations in Franklin Court occurred in 1953. These digs revealed foundation remains beneath Orianna Street and encouraged further exploration. Archeologists returned to Franklin Court in 1960. The excavations revealed more remains of the Franklin home, including a section of the cellar kitchen floor, additional foundation walls, and a privy pit.

NPS Photo

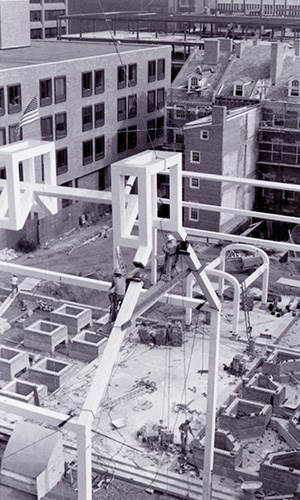

Reimagining Franklin Court

Philadelphia architects Robert Venturi, William Rauch, and Denise Scott Brown designed space frames following dimensions recorded in Benjamin Franklin's property insurance. The steel-framed "ghost structures" give scale to the property. The Franklin family house was large for the 18th century city, and unusual because it sat within a garden court, away from Market Street. Viewing portals provide visitors with a glimpse of the original cellar kitchen to the Franklin mansion.Since its opening in 1976, Franklin Court has received acclaim for its bold and innovative interpretation. In 1985, the Venturi and Rauch firm won the Presidential award for its design excellence.

In 2013, the site was renovated for new generations. New accessibility improvements made the ghost structure accessible to visitors with mobility impairments. But the most notable change occurred below the courtyard—the Underground Museum, which opened in 1976, closed to make way for the Benjamin Franklin Museum, which explores Benjamin Franklin's life and legacy using artifacts, videos, and computer interactives.