Last updated: February 22, 2022

Article

Ulysses S. Grant, Slavery, and the "Hiring Out System" in St. Louis

Missouri Secretary of State's Office

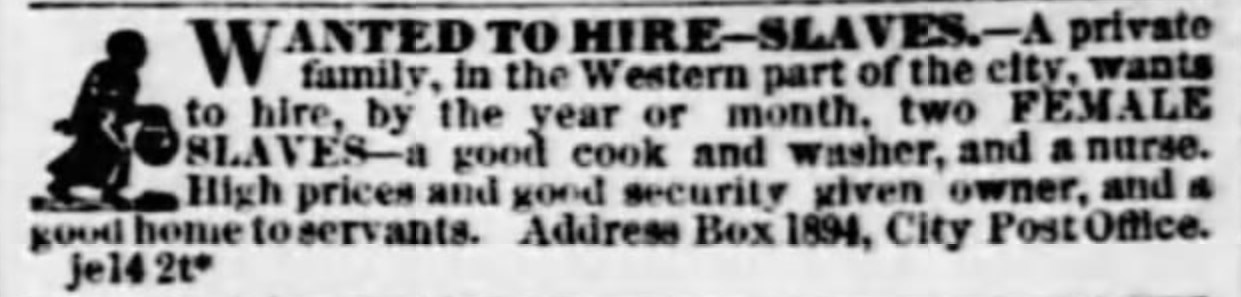

In the years before the American Civil War, enslaved African Americans sometimes worked away from the property of their enslavers. At times, they labored for other enslavers or for people who owned no enslaved people and were too poor to purchase enslaved laborers outright. Enslavers found that in some situations, they could make more money by contracting their enslaved laborers to others rather than having them work on their own property. The “hiring out” system of contracting enslaved labor became increasingly popular in the South during the 1850s when Ulysses S. Grant lived in St. Louis at White Haven, a plantation owned by his father-in-law Frederick F. Dent. The system of slave hiring grew especially in the upper South. As the profitability of crops such as tobacco and rice diminished and enslavers found that they had an excess of enslaved labor on their properties, they used the hiring out system to profit from slavery in another way. For example, enslaved laborers in urban cities like St. Louis could end up being hired out to work as artisans, blacksmiths, carpenters, and laborers as the value of cash crops decreased in the 1850s. However, the hiring out system also allowed enslaved people to build new networks across properties and gain power through negotiations where they would play off the needs of both their enslavers and hirers.

Hiring out enslaved people allowed for the strengthening of the “peculiar institution” as the profitability of enslaved agriculture diminished in the upper South. Enslavers in the upper South who struggled financially often made money by selling enslaved people “down the river” to the more profitable sugar and cotton plantations of the deep South. However, enslavers also relied on the hiring out system to continue profiting off of slave labor. The hiring out system also helped the upper South remain a society based around the institution of slavery. Enslavers could make a larger profit long term by hiring out people instead of selling them outright. Furthermore, hiring out allowed poorer whites to have a “taste” of mastery through hiring and further engrain enslaving Black people as a signifier of social status. Additionally, historian Johnathan D. Martin contends in his book Divided Mastery that “hiring allowed whites from different classes to ‘share’ slaves among themselves in a way that reassured them of their power and superiority.” Therefore, hiring-out acted not only as an economic boon for enslavers but also as a tool for perpetuating the myth of racial solidarity among whites in the Old South, where the enslavement of Black people functioned as the unifying force among white Southerners. As a result, many poor whites aspired to become enslavers to fulfill their personal and societal desires. Meanwhile, wealthy white enslavers used their status over Black Southerners as justification for their rule over poorer white Southerners as well.

State Historical Society of Missouri

For enslaved people, the hiring-out system presented new opportunities as well as new perils. When enslaved people worked on a new plantation, they often found themselves separated from their families and community ties for weeks on end. Without support from their friends and family, enslaved people were more susceptible to violence from their hirers. Additionally, without their loved ones to lean on, hired-out enslaved people could have a more challenging time emotionally and psychologically dealing with their new environment and any violence from their hirers. However, enslaved people could go home if given a pass to travel back to their plantations to see their families. Granting passes was totally at the discretion of the hirer, however, so enslaved people were at the whim of those hiring them to determine if they would be able to see their family for the year. Enslaved could try to run away, of course, but in leaving without a pass they risked often violent punishment if captured. At White Haven, Julie Dent Grant mentions that men enslaved by her father would ask her for favors, such as visiting other plantations and seeing their wives. They knew that her father could not say no to Julia, so they tried to get permission by bribing Julia.

Hiring out also presented enslaved people with expanded communication networks. Those sent to different plantations and properties in an area could listen to gossip, rumors, and news that their hirers or enslaved people on that property had heard. In turn, when an enslaved person returned to their home community, they could spread this information to their local slave community. Thus, communication by enslaved people across plantations acted as a significant way for the enslaved to distribute vital news and information to each other. Despite most enslaved people lacking the ability to read and write, they learned the news of the day and spread that news across great distances, including rumors of freedom.

Often taking on extra work after their tasks for the day had been completed, enslaved artisans could possibly make money while hired out. People such as farriers, carpenters, and seamstresses were the best compensated for their skilled labor. Many enslaved people regularly hired out were able to make enough off these earnings to purchase their own freedom and later the rest of their family. However, these wages could also easily be confiscated by their hirer or enslaver, so the prospects of freedom were still slim. A prominent example of an enslaved person purchasing their freedom through the hiring out system in St. Louis is that of Elizabeth Keckley, who worked as an enslaved seamstress and became popular among the women of St. Louis’s aristocracy due to her superb needlework. Keckley’s skill proved so popular that she was able to purchase her own freedom, and later that of her son, from her earnings making dresses in 1855. Eventually, Keckley’s work became so well known that Mary Todd Lincoln brought her to the White House to be the First Lady’s personal dressmaker.

As the hiring out system grew, so too did the ability of enslaved people to negotiate with their hirers and enslavers. Slavery had always been a system of negotiation between enslaved and enslavers, albeit one in which enslavers held vastly more power in the negotiation. Enslavers could threaten violence, sell off family members, and hand out other punishments while enslaved people could refuse work or commit deliberate sabotage. Thus, a two-way negotiation developed between the two parties, with the enslaver having far more power over the enslaved, but the enslaved still having some influence in trying to shape their situation. With the growth of the hiring out system, this dialectic negotiation transformed into a triangular one with the addition of hirers, who would negotiate wages, food, shelter, and clothing with the enslaver (and sometimes the enslaved) when establishing a one-year work contract.

Meanwhile, hirers also haggled with enslavers over the price of their enslaved labor. Enslaved people could play off the conflict between enslavers and hirers to create the best situation for themselves. Some enslaved people would rather be hired out than be stuck at a plantation they hated or where they had limited means to earn funds. Other enslaved people could make themselves seem unattractive hires to stay at home with their families. Enslaved workers could refuse to work when hired out, while enslavers could refuse to hire out an enslaved person, and a perspective hirer could refuse to hire out someone they saw as being of poor character or skill. All three parties tried to get the best situation for themselves by playing the other two parties off one another. A hirer might allow an enslaved person to make more money on their own or give a larger food ration to entice them to want to be hired out by them. Meanwhile, enslaved laborers could make themselves look attractive to potential hirers to go where they thought they could get the best situation for themselves. Enslavers in turn played off both to make the most money off the hiring contract as possible. However, enslavers might be leery of hirers who posed a threat to their desire to have total control over the people they enslaved. If a potential hirer offered too many incentives to enslaved workers, then an enslaver might refuse to sign the contract in order to prevent any possible loss of a sense of mastery.

Missouri Secretary of State's Office

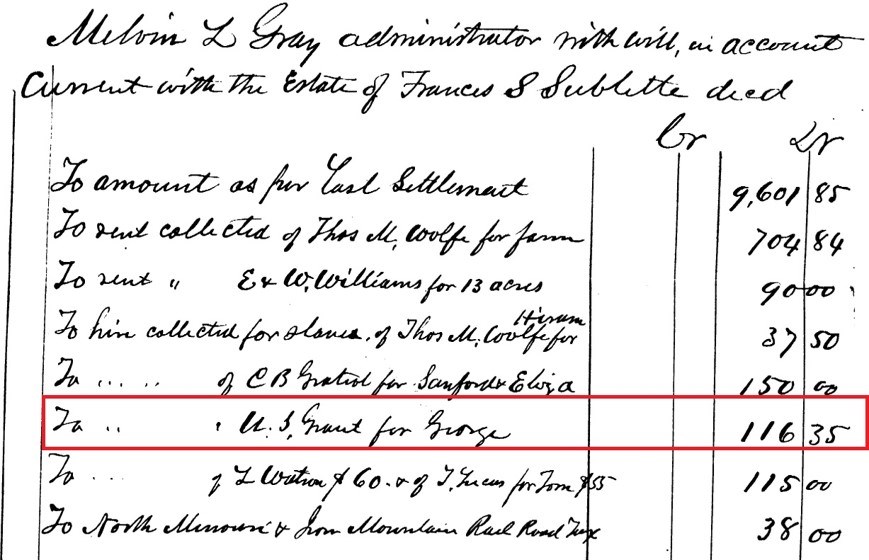

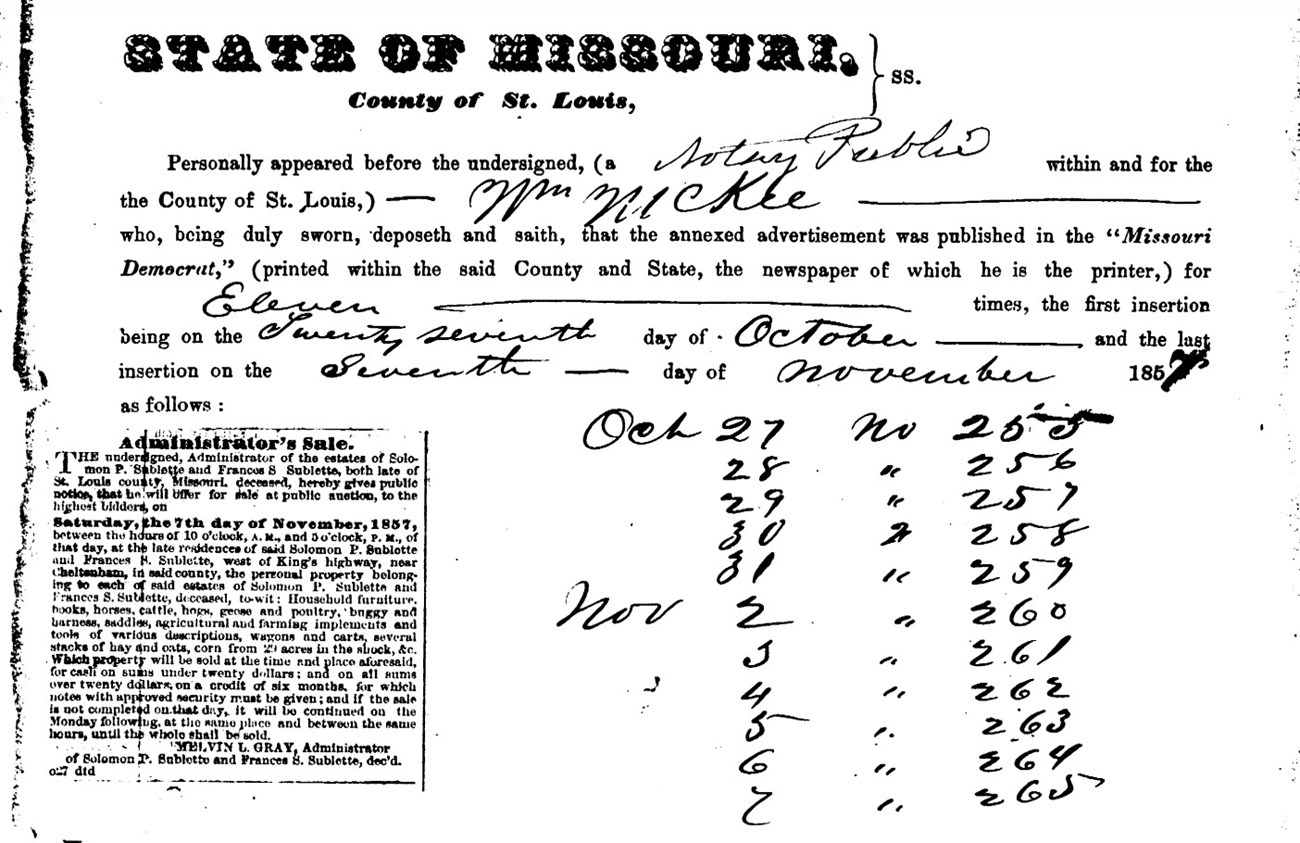

At White Haven, Grant acquired an enslaved man named William Jones, who most likely worked alongside him on his eighty acres on the property. When Grant left the farming business in 1859 to start a brief and unsuccessful career in real estate, he freed Jones according to paperwork from the St. Louis Courthouse. However, William Jones was not the only enslaved person who worked with Grant and his family at White Haven. Grant also had two enslaved hired out to work in the fields with him during the 1858 growing season. In a letter to his sister Mary, Grant remarked that, “I have now three negro men, two hired by the year and one of Mr. Dent’s, which with my assistance will enable me to do farming pretty well.” It was common for enslaved people to begin their contracts on New Year’s Day for the entirety of the year, hence Grant hiring by the year comment. George, a twenty-one-year-old laborer, was one of the men hired by Grant. George had been owned by the recently deceased Frances Sublette, whose husband and extended family gained their wealth from the fur trade. Grant hired George from the Sublette estate for $116.35 according to 1857 Probate Court records. Beyond these scraps of evidence, little is known about George and what his life was like while under Grant’s authority at White Haven.

Grant’s relationship with the hiring out system continued in 1859 and 1860. When Grant discussed with his father a plan to move to Covington, Kentucky (which never ended up happening), he mentioned hiring out one of the enslaved children at White Haven. Col. Dent told Grant he should take the enslaved man to Kentucky with the Grants and let him learn the farrier’s business. But if Grant’s anti-slavery father did not want him to bring the enslaved man to Kentucky, Grant remarked that he could “leave him [in St. Louis] and get about three dollars per month for him now, and more as he gets older.” In other words, Grant seriously contemplated hiring out this young enslaved child to make money for himself and Julia’s father. Additionally, Grant’s father-in-law informally gifted his daughter Julia four enslaved people, Eliza, Dan, Julia, and John. When the Grants moved to Galena. Illinois, in 1860, they left the enslaved laborers behind in St. Louis. “We rented our pretty little home [in St. Louis] and hired out our four servants to persons who we knew and who promised to be kind to them,” Julia Grant recalled in her Personal Memoirs. Since the enslaved people were still technically the legal property of Col. Dent, the money they made went to him.

Col. Frederick Dent probably also hired out people he enslaved to support himself in the late 1850s and early 1860s while struggling financially. The hiring out system might help explain the decrease between the 1850 and 1860 Slave Schedule in the U.S. Census, where the number of people enslaved by Frederick Dent is thirty in the former but only seven in the latter. Census takers would only count the number of people on the enslaver’s property when they stopped by or questioned neighbors if the homeowner was not available. Slave schedules make no distinction between people enslaved by the person listed or simply hired out by them.

White Haven’s relationship to the hiring out system in the 1850s is typical of the period. Less wealthy farmers like Grant were able to hire out additional labor to help with their farming needs, while larger enslavers like his father-in-law could hire his out instead of selling them to make additional money. The enslaved people at White Haven had their experiences shaped by slavery and most certainly tried to shape the system to fit their needs as well. Hiring out separated loved ones for extended periods of time but also gave new opportunities for enslaved people to purchase their freedom. Thus, the system both weakened the grip of slavery by allowing enslaved people to gain greater power in negotiations but also strengthened the system by allowing large-scale enslavers to survive and thrive as plantation agriculture diminished. Additionally, it allowed for slavery to continue expanding in regions like Missouri and other parts of the Upper South as the demand for renting enslaved labor grew. By giving poorer whites a taste of mastery, they too would aspire to enslave people of their own and continue growing the institution of slavery as it remained at the center of Southern society and power.

Further Reading

Berry, Daina Ramey. The Price for Their Pound of Flesh: The Value of the Enslaved, from Womb to Grave, in the Building of a Nation. New York: Beacon Press, 2017.De Bow, J.D.B. The Interest in Slavery of the Southern Non-Slaveholder. Charleston: Evans & Cogswell, 1860.

Deyle, Steven. Carry Me Back: The Domestic Slave Trade in American Life. New York: Oxford University Press, 2006.

Grant, Julia Dent. The Personal Memoirs of Julia Dent Grant. New York: Putnam Press, 1975.

Johnson, Walter. Soul By Soul: Life Inside the Antebellum Slave Market. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1999.

Kennington, Kelly M. In the Shadows of Dred Scott: St. Louis Freedom Suits and the Legal Culture of Slavery in Antebellum America. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2017.

Martin, Jonathan D. Divided Mastery: Slave Hiring in the American South. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2004.

Merrit, Keri Leigh. Masterless Men: Poor Whites and Slavery in the Antebellum South. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2017.