Last updated: January 14, 2021

Article

Ulysses S. Grant's Path to Victory: The 1864 Overland Campaign

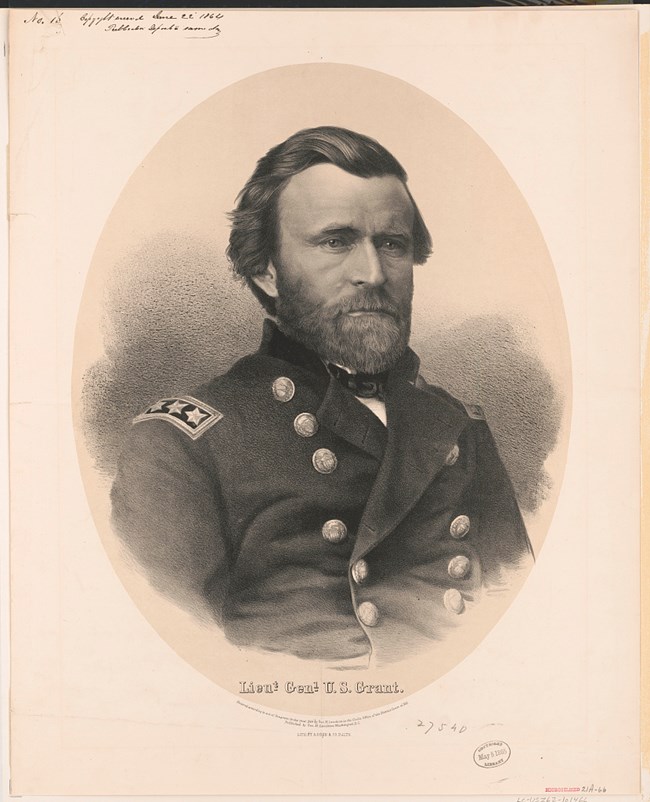

Lithograph by A. Hoen (Library of Congress)

When Ulysses S. Grant took command of all United States armies in March of 1864, he promised to change how the Union war effort was being conducted. 1864 was a crucial "make it or break it" year in the Civil War. The nation had already gone through unspeakable bloodshed and war weariness was at an all-time high. Many soldiers who had enlisted in the U.S. military at the beginning of the war in 1861 had signed up for a three-year term that was about to expire. Would they re-enlist? And perhaps most importantly, President Abraham Lincoln was up for re-election as the Union hung in the balance. As commander of all Union armies, the path to victory laid on the shoulders of Lt. General Ulysses S. Grant, who strove to find a winning strategy and accomplish Union war aims as quickly as possible.

When General Grant formulated his plans for the upcoming spring campaign of 1864, he endeavored to bring a unifying purpose to his forces. Destroying or capturing Confederate armies and restricting their ability to wage war became the foremost objective. Grant hoped that “so far as practicable all the armies are to move together and towards one common [center].” Earlier in the war, Grant observed how “various [Union] armies had acted separately and independently of each other, giving the enemy an opportunity often of depleting one command, not pressed, to reinforce another more actively engaged.” To accomplish this end, Grant’s main objective was defeating General Robert E. Lee and his Army of Northern Virginia. Defeating Lee was important because his army had been the most successful of all Confederate armies and when that army ultimately fell, the Confederate war effort would be doomed.

Grant relayed the importance to capturing Lee’s army to General George Gordon Meade, the commander of the Army of the Potomac. “Lee’s army will be your objective point. Wherever Lee goes, there you will go also.” While previous Union commanders of the Army of the Potomac believed that Richmond itself was a bigger prize, Grant realized that even with Richmond in Union hands, the war would continue as long as Lee’s army was still on the field and supported by the Confederate population. This situation had a precedent in U.S. history. During the American Revolution, the British captured the Continental capitol at Philadelphia. However, Washington’s army remained on the field and the Continental Congress simply moved its base of operations. Grant’s strategy proved true when Richmond was finally captured on April 2-3 1865. Even though the capitol was now in U.S. hands, Lee’s army escaped and fought on for another week. While Grant’s main objective was defeating Lee, he planned simultaneous campaigns in support of his Army of the Potomac to strangle the Confederacy. These included campaigns in the Trans-Mississippi, Shenandoah Valley, the James River east of Richmond, and a major campaign against Atlanta led by Grant’s trusted subordinate, General William T. Sherman.

While Grant was planning offensive strategies, he also assuaged Lincoln’s fears about a possible Confederate northern incursion. “It was necessary to have a great number of troops to guard and hold the territory we had captured, and to prevent incursions into the northern states.” He went on to say that the troops “could perform this service just as well by advancing as by remaining still; and by advancing they would compel the enemy to keep detachments to hold them back, or else lay his own territory open to invasion.” Lincoln, seeming to understand Grant’s purpose to use all the Union armies simultaneously towards a common purpose, stated “Oh, yes! I see that. As we say out west, if a man can’t skin, he must hold a leg while somebody else does.”

In formulating his plans for the 1864 campaign, Grant also began his excellent working relationship with President Lincoln. Despite having a mutual respect for each other, they never met personally until late March 1864. Lincoln expressed his disappointment in the “procrastination” of past commanders. He went on to tell Grant that he wanted “someone who would take responsibility and act and call on him for all the assistance needed, pledging himself to use all the power of the government in rendering such assistance.” Grant responded by assuring Lincoln that he would do his best with the means available to him and to avoid “annoying” Lincoln or the War Department. Lincoln, in his last letter to Grant before the Overland Campaign was set to open on May 4, expressed his “entire satisfaction with what you have done up to this time.” He called Grant “self-reliant and vigilant.” He also expressed a wish to not put “any constraints or restraints” upon Grant, thereby showing his trust in Grant’s generalship. He also let Grant know, “if there is anything wanting which is within my power to give, do not fail to let me know it . . . now with a brave army and a just cause, may God sustain you.” On May 4, 1864 Lt. General Ulysses S. Grant put his plan in motion and advanced on all fronts for a push to finally end the American Civil War.