Last updated: April 29, 2021

Article

Ulysses S. Grant's Experiences During the Camp Jackson Affair

Missouri Historical Society

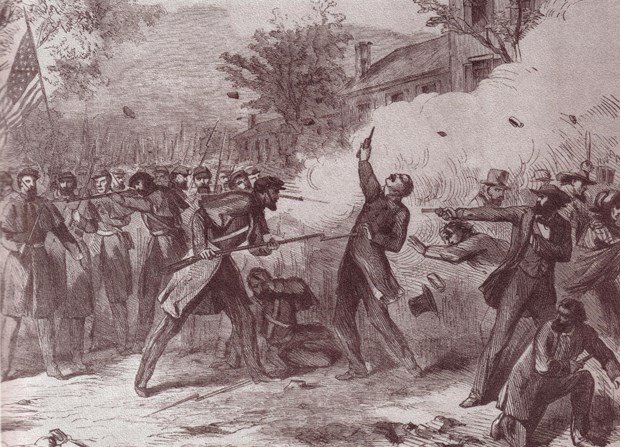

Missouri was very divided in these early days of the war. Through slavery and commerce down the Mississippi River, the state had ties to states that would become a part of the Confederacy. Through industrialization, railroad trade, and immigration (especially Irish and anti-slavery Germans) the state also had ties to the North. Newly elected Governor Claiborne Fox Jackson was sympathetic to the Confederacy and called for a state constitutional convention to debate the merits of secession in February. Although the convention voted overwhelmingly against secession (98 to 1), Governor Jackson and his allies still maneuvered for Missouri’s secession by using questionable methods. Jackson refused President Abraham Lincoln’s call for troops after the firing of Fort Sumter. With approval from the state legislature, he began raising and equipping the Missouri State Guard, a state militia whose members were mostly secessionist. The State Guard began threatening the federal arsenal in St. Louis, which housed many weapons and gunpowder. Other federal arsenals in the South had been overtaken by Confederate forces, so the threat to the St. Louis federal arsenal was credible. Moreover, Jackson supported a bill that placed the St. Louis City Police under state control, weakening protection of the arsenal. Soon the Missouri State Guard established an encampment just west of downtown St. Louis which they named after their governor, Camp Jackson.

General William Harney was a conservative commander in charge of federal troops in St. Louis. Underneath him was Captain Nathaniel Lyon, who was tasked with defending the arsenal alongside Frank Blair, an influential U.S. Congressman from St. Louis. They began raising their own pro Union militia, which through Blair’s influence became sanctioned by the Lincoln administration. In St. Louis to help with mustering troops in nearby Belleville, Illinois, Ulysses S. Grant wrote to his wife Julia about this development. “There are two armies now occupying the city, hostile to each other, and I fear there is great danger of a conflict which, if commenced must terminate in great blood shed and destruction of property without advancing the cause of either party.” To safeguard surplus weapons at the arsenal, Lyon shipped them across to Illinois for safe keeping.

Following the Camp Jackson Affair, General Harney struggled to keep the peace between secessionist and unionist elements Missouri. On May 21, Harney met with Sterling Price, a former governor of Missouri. They worked out an agreement in which Price’s state forces kept order in Missouri and the federal government would not interfere in state affairs, but the federal army would regulate affairs in St. Louis. By this agreement, General Harney conceded to the heavily pro secessionist state authorities the right to run state affairs. Naturally, Frank Blair, Nathaniel Lyon and their allies were incensed by this and they successfully maneuvered for Harney’s removal and for Lyon to replace him. Soon after, Lyon was promoted to Brigadier General. He bluntly stated his uncompromising unionist stance in a meeting with Claiborne Fox Jackson, Sterling Price and Frank Blair at the Planters House in St. Louis. When Price sought to continue the agreement that he worked out with Harney, Lyon would hear none of it. Irritated and uncompromising, Lyon allegedly stood up during the middle of the meeting and stated angrily, “rather than concede to the State of Missouri for one single instant the right to dictate to my Government in any matter however unimportant…I would see you and every man, woman and child in the State, dead and buried.” As he finished, he turned to Governor Jackson with the grand finale of his speech, “this means war.” From that moment the Civil War was officially underway in Missouri.

Lyon would not see the fruition of his uncompromising unionist stance, dying at the Battle of Wilson’s Creek on August 10, 1861. Ulysses S. Grant remembered the Camp Jackson Affair and praised Lyon and Blair in his Personal Memoirs. “I have little doubt that St. Louis would have gone into rebel hands, and with it the arsenal with all its arms and ammunition” had Lyon and Blair allowed Camp Jackson to stand. “As soon as the news of the capture of Camp Jackson reached the city the condition of affairs was changed. Union men became rampant, aggressive, and, if you will, intolerant. They proclaimed their sentiments boldly, and were impatient at anything like disrespect for the Union.”

John Y. Simon, ed., The Papers of Ulysses S. Grant, Volume 2: April-September 1861. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1969. pp. 26, 30-31.

Louis S. Gerteis, Civil War St. Louis. University Press of Kansas, 2001.

Ulysses S. Grant, Personal Memoirs of Ulysses S. Grant. New York: Charles Webster Publishing, 1885.

Louis S. Gerteis, Civil War St. Louis. University Press of Kansas, 2001.

Ulysses S. Grant, Personal Memoirs of Ulysses S. Grant. New York: Charles Webster Publishing, 1885.