Last updated: March 1, 2021

Article

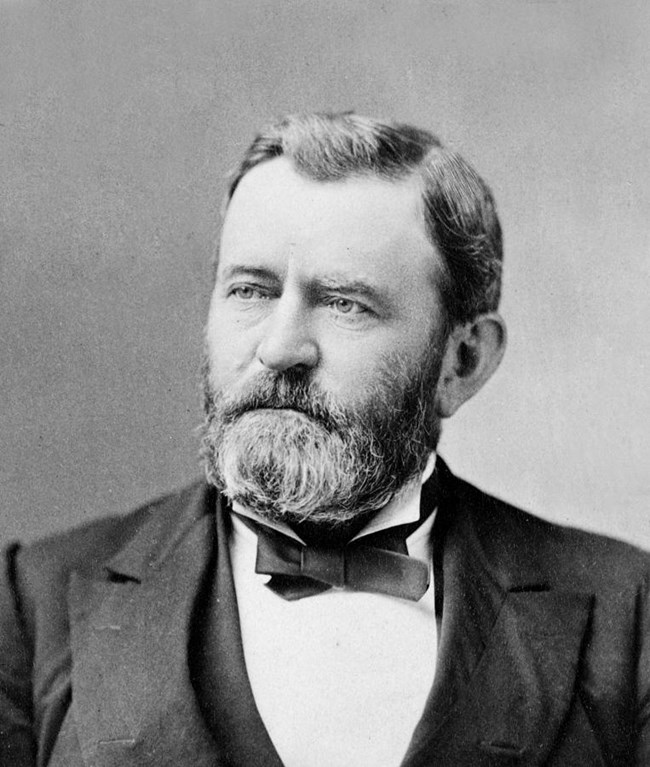

Ulysses S. Grant's Controversial Visit to Ireland

Library of Congress

At the start of 1879, former General and President Ulysses S. Grant entered the last year of his world tour. By this point he and his wife Julia had already traveled extensively throughout Europe, Egypt, and the Holy Lands of Jerusalem. He had been welcomed by heads of state and ordinary people alike throughout the tour, widely acclaimed as the symbol of American generalship and statesmanship. However, Grant soon visited the first country on his world tour with decidedly mixed feelings about him: Ireland.

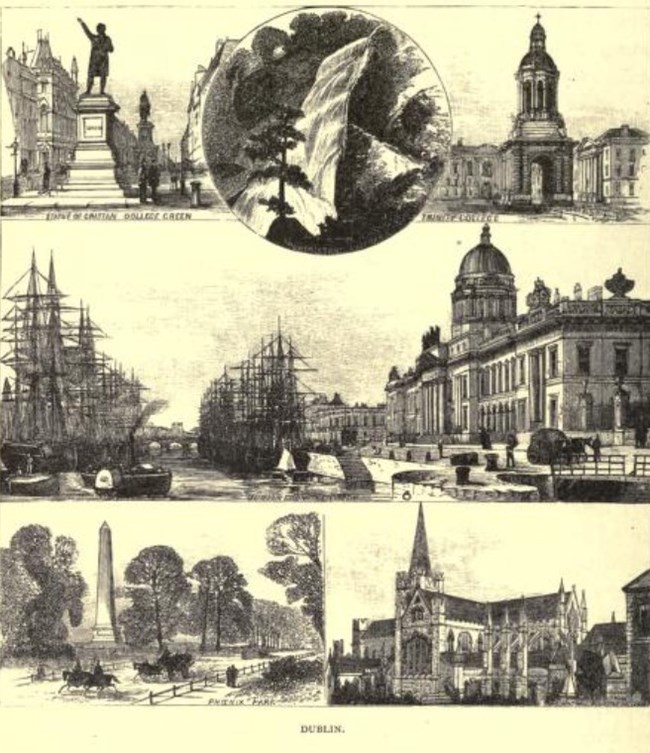

Grant spent a relatively short time in Ireland, arriving in Dublin on January 3, 1879 and departing the country five days later. During this time Ireland was under the rule of Great Britain, a point of longstanding anger and grievance among many Irish. Instead of an Irishman greeting Grant upon his arrival, an Englishman, the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland, the Duke of Marlborough invited Grant to lunch. Later, Grant was received and welcomed warmly by John Barrington, the Irish-born Lord Mayor of Dublin. Barrington associated Grant with Lincoln and declared, "Ireland mourned for [Lincoln's] loss when she heard the news that the great disciple of freedom had been struck down. A truly great general took his place and carried out the work that had been begun...the shackles of the negro and slavery disappeared from America, every part of which is now free." In other parts of Ireland, however, Grant was not viewed with this amount of esteem. When the city of Cork heard that Grant might pay them a visit, its leaders debated whether to welcome him into their city at all. Perhaps aware of this debate, Grant chose not to visit Cork.

The main grievances against Grant dated back to his Presidency. Critics argued that Grant didn't do enough for the cause of Irish independence, and in fact hindered it. During Grant’s presidency, the Fenian Brotherhood was dedicated to an independent Ireland totally free from Great Britain. Grant attempted to stop the Fenian Brotherhood during his presidency and some Irish citizens, according to historian Edwina Campbell, blamed Grant for not "receiving the Fenian leader who had visited the United States during his presidency." The second main complaint was that many Irish Catholics claimed Grant supported anti-Catholic policies during his presidency. One official claimed that Grant "went out of his way to insult their religion."

During the Civil War, a large Irish population in America overwhelmingly supported the Union cause. Recent scholarship puts 150,000 Irish fighting for the Union while 30-40,000 fought for the Confederacy. While settling in the United States and serving in its military during the war, many Irish American immigrants still maintained a burning desire to see Ireland rid of British rule. They enthusiastically supported the Fenian movement and sought to challenge the British by making raids into Canada, which was still under British rule at that time.

While the Fenians began raiding Canada during President Andrew Johnson's term, they continued into Grant's presidency in the late 1860s. The Fenians used bases in Vermont and New York for these forays into Canada. Although none of the raids achieved their goals of an independent Ireland, they gave the Grant administration a few headaches.

More than anything, these raids threatened to destabilize fragile talks between Britain and the United States regarding numerous political issues. The first revolved around the “Alabama Claims.” During the Civil War, the British built numerous ships, including the Alabama, that were then sold to and used by the Confederacy. These Confederate ships caused immense damage to U.S. shipping during the Civil War. The Grant administration now sought a way to recoup some of these losses from the British government. Additionally, the Grant administration wanted to resolve a longstanding border dispute with British Canada and establish equitable fishing rights in Canadian waters. According to historian Charles Calhoun, during these negotiations the British "raised the question of claims against the United States growing out of the Fenian raids into Canada." Although U.S. diplomats objected that this topic was not within the scope of their negotiations, President Grant felt that he had to do something about the Fenians.

Around the World with General Grant, Volume 1

To stop the issue from hampering negotiations between Britain and the United States, Grant issued a proclamation on May 24, 1870. He warned American citizens against "aiding, countenancing, abetting or taking part in such unlawful proceedings." If the Fenians continued "committing such illegal acts they will forfeit all right to the protection of the Government." This proclamation ended most Fenian raids, although Grant also pardoned Fenians in U.S. custody. In any case, the end of Fenian raids played a role in successfully resolving international arbitration between the United States and Great Britain.

Accusations of anti-Catholicism against President Grant stemmed from an 1875 speech he made at a reunion of the Army of the Tennessee in Des Moines, Iowa. This speech was partly a reaction to the Democratic legislature in Ohio mandating that the state "provide inmates of prisons and state hospitals access to religious instruction in their own faiths." Protestants had long feared that a growing number of Catholic immigrants would be more loyal to the Pope than to the U.S. government, and that efforts would soon be made to use public funds to subsidize Catholic schools around the country. Many Republicans, including Grant, embraced these fears and tried to make a political issue out of them. During his speech, Grant remarked that "if we are to have another contest in the near future of our national existence I predict that the dividing line will not be Mason & Dixon . . . but between patriotism & intelligence on the one side & superstition, ambition & ignorance on the other." He went on to say, "Encourage free schools and resolve that not one dollar of money appropriated to their support . . . shall be appropriated to the support of any sectarian school." Even though he did not include the word "Catholic" in his speech, many Catholic journals condemned Grant and claimed his use of terms like “superstition,” “ignorance,” and “sectarian” were direct attacks against their religion.

Claims against Grant being "anti-Catholic" made the newspapers in the United States during his travels in Ireland. General William T. Sherman, whose wife was Catholic and who had a son about to join the priesthood, defended Grant in the press. Grant later remarked that his comments were not intended to call out the Catholic church, saying "if any Methodist friends should ever undertake to divert public funds to the support of sectarian schools, they and I would be at outs." Near the end of his Irish trip, Grant remarked that "I could not think of having seen your little island with out putting my foot on your soil." After all, Grant’s own ancestors had once lived in County Tyrone, Northern Ireland. In Grant’s view, America offered "a home for all who find themselves limited on this side of the water. We will make you all welcome when you come here to see us-and more than that, we will make you citizens."

Calhoun, Charles W. The Presidency of Ulysses S. Grant. Lawrence Kansas, University Press of Kansas, 2017, pgs 172-173, 332, 505, 513.

Kahan, Paul. The Presidency of Ulysses S. Grant: Preserving the Civil War's Legacy. Yardley, Pennsylvania, Westholme Publishing, LLC, 2018, pgs 9, 84-85.

John Y. Simon, ed., The Papers of Ulysses S. Grant, Volume 20: November 1, 1869-October 31, 1870. Carbondale. Southern Illinois University Press, 1995, pg. 151.