Last updated: April 1, 2024

Article

Ulysses S. Grant Reacts to the Firing on Fort Sumter

Galena State Historic Sites

During the secession crisis before Fort Sumter, and with the possibility of civil war erupting at any moment, Grant’s military past was generating interest among the people he dealt with in his family business. He remembers in his memoirs, “we had customers in all the little towns in south-west Wisconsin, south-east Minnesota and north-east Iowa. These generally knew I had been a captain in the regular army and had served through the Mexican War. Consequently, wherever I stopped at night, some of the people would come to the public-house where I was and sit till a late hour discussing the probabilities of the future.” The former army officer now found himself considered a local authority on the crisis and the possibility of war. He was wrong on ultimately one assessment, expressing his views that the war would be a short one, later admitting, “I continued to entertain these views until after the battle of Shiloh.” [ fought almost exactly one year later.]

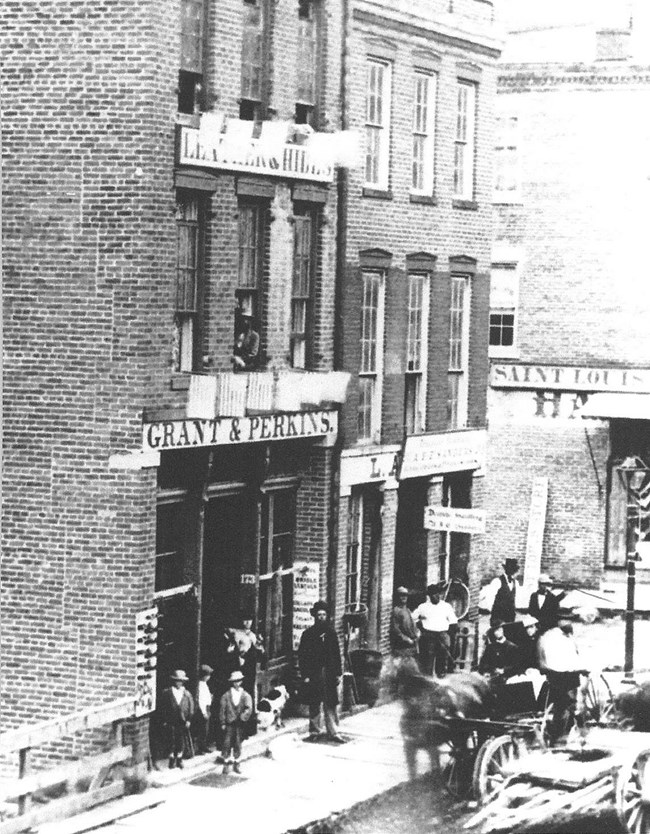

As Grant’s status as a former regular officer in the US Army was known to the people in the Galena area, he was destined to take a leading role in the activities of that town on the outbreak of the Civil War. When President Lincoln called up 75,000 volunteers to serve ninety days in the aftermath of Fort Sumter Galena was awash in patriotism. Grant remembered that advertisements throughout town called for the citizens to gather at the courthouse for a meeting. Businesses stopped. Grant wrote in his memoirs, “all was excitement; for a time, there were no party distinctions; all were Union men, determined to avenge the insult to the national flag. The courthouse meeting was filled and soon Grant found himself presiding the meeting. This was probably as he reflected, “although a comparative stranger…I had been in the army and had seen service.” After rousing patriotic speeches by leading men of Galena including John A. Rawlins and Elihu Washburne, the meeting resulted in a call for volunteers in Galena to form a company of soldiers to help fill Illinois’s original quota of six regiments. The captain of the company was to be elected. Grant remembered, “I declined the captaincy before the balloting but announced that I would aid the company in every way I could and would be found in the service in some position if there should be a war.” Walking home from that meeting he remarked to his brother Orvil, “I think I ought to go into the service.” His days in the family business was over. “I never went into our leather store after that meeting, to put up a package or do other business.”

Ulysses S. Grant’s personal letters during the aftermath of Fort Sumter reveal a deep commitment to the Union. He wrote his slave owning father-in-law Colonel Frederick Dent back in White Haven, Missouri on April 19, “the times are indee[d] startling but now is the time particularly in the border slave states, for men to prove their love of country…but now all party distinctions should be lost sight of and evry [sic] true patriot be for maintaining the integrity of the glorious old Stars and Stripes. [sic] He goes on to say, “no impartial man can conceal from himself the fact that in all these troubles the South [sic] have been the aggressors and the Administration has stood purely on the defensive.” He also prophesizes to his slave owning father-in-law, “in all this I can but see the doom of Slavery.” Two days later he writes his own father, Jesse, “whatever may have been my political opinions before I have but one sentiment now. That is we have a Government, [sic] and laws and a flag and they must all be sustained.” He also offers a clue in this letter to why he did not accept the Captaincy and immediately go back into the army. He wrote his father, “I do not wish to act hastily or unadvisedly in the matter, as there are more than enough to respond to the first call of the President. I have not yet offered myself, I have promised and am giving all the assistance I can in organizing the Company [sic] whose services have been accepted from this place.” [Galena] In reality Grant was looking for a better opportunity, a colonelcy. That opportunity would find Grant in a matter of a few months beginning his second career in the army which ultimately led to the presidency.