Last updated: November 22, 2021

Article

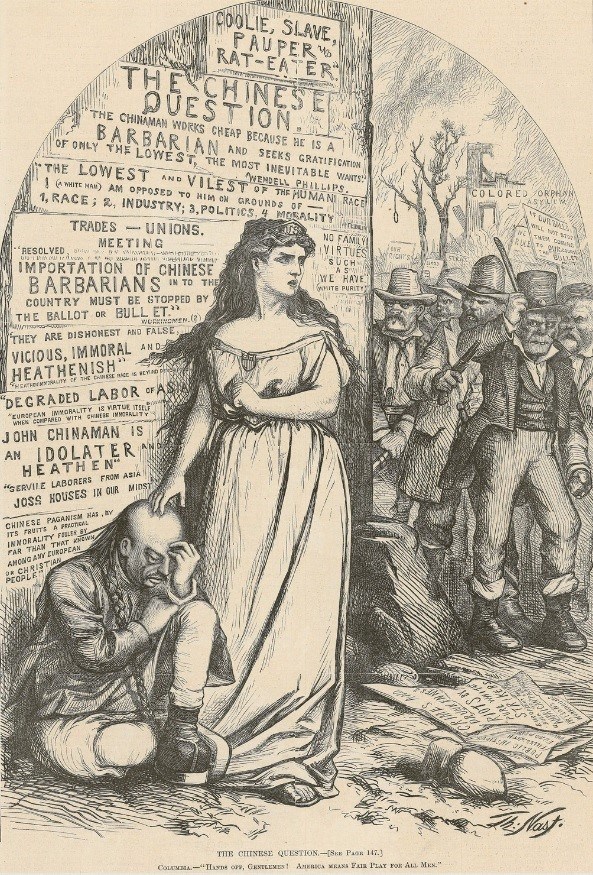

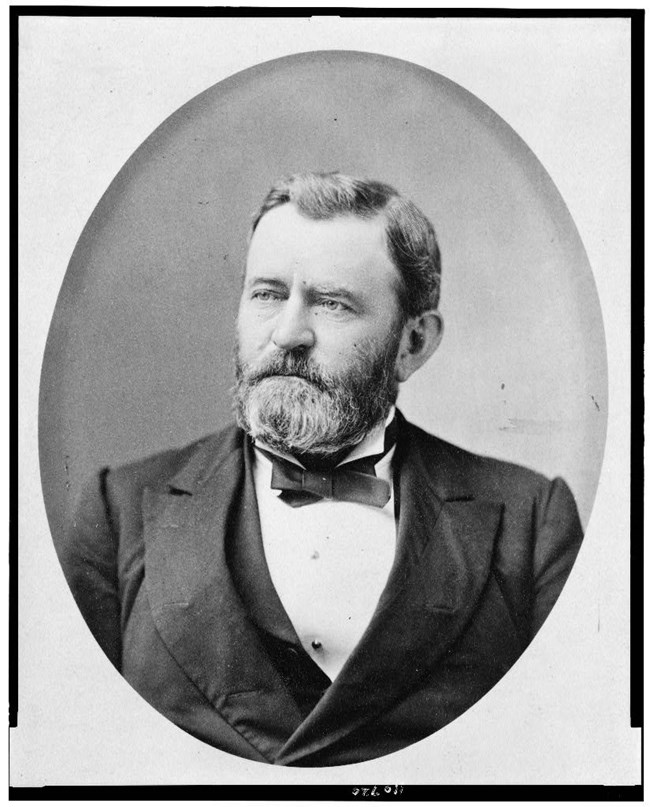

Ulysses S. Grant, Chinese Immigration, and the Page Act of 1875

Princeton University Library

Many people living in the United States today may be surprised to learn that the federal government largely divorced itself from immigration policy for nearly 100 years. To be sure, some restrictions on citizenship were established during the republic’s formative years. For example, the Naturalization Act of 1790 restricted U.S. citizenship to immigrants who were defined as “white” until 1870, when it was expanded to include immigrants of African descent. Furthermore, Atlantic seaboard states such as New York and Massachusetts used state “poor laws” to prevent some immigrants from settling within their borders before the Civil War. However, only one federal law existed to restrict immigration between 1787 and 1875. That law, which was passed in 1803 but poorly enforced, banned the "importation" of any free "negro, mulatto, or other person of color" to the United States in the wake of the Haitian Revolution. However, the federal government's relationship to immigration policy changed on March 3, 1875, when President Ulysses S. Grant signed the Page Act into law.

The Page Act of 1875 was the product of many political factors, including concerns over involuntary servitude, declining wages in the labor market, prostitution, and popular racist stereotypes about people of Asian descent. The act established three different goals. First, it authorized the use of federal agents at immigration ports to search and question “any subject of China, Japan, or any Oriental country” to determine if that person had come “without their free and voluntary consent, for the purpose of holding them to a term of service." If agents suspected that the person had come involuntarily to engage in “lewd and immoral purposes” while in the U.S., they could be expelled. Second, it effectively banned the immigration of Chinese women by portraying most of them as arriving in the U.S. solely to work as prostitutes. Finally, the act banned people who had been convicted of felonies in their home country from immigrating to the United States.

Anti-Asian and anti-Chinese sentiment had long existed in the U.S., especially in Western states like California and Nevada. The first major wave of Chinese immigration began in the wake of the California Gold Rush of 1848. Chinese men during the Civil War era worked in the West as manual laborers in railroad construction, mining, levee building, and factories, among other occupations. Looking to exploit this labor supply and keep costs as low as possible, many businesses hired Chinese laborers for low wages. Most Chinese men struggled to support themselves and did not earn enough money to bring their wives and children to the U.S. Although it is tough to measure in exact terms, prostitution rings did emerge with some frequency in California. According to historian Judy Yung, Chinese secret societies known as “tongs” oversaw a prostitution ring in San Francisco. Tongs would sometimes pay smugglers to kidnap Chinese women and remove them from their home country. Interestingly, prostitution was a legal occupation under California law dating back to the 1850s, and men of all races would have frequented prostitution houses. Rather than punishing men or placing a state ban on prostitution, however, the Page Act targeted Chinese women as threatening the institution of marriage.

Many white laborers and politicians vocally complained about Chinese immigration and sometimes resorted to violence against Asians. Workers argued that an oversupply of Chinese laborers lowered wages and took jobs away from white workers. California labor leader Denis Kearney famously argued in the 1870s and 1880s that Chinese laborers were tools of wealthy capitalists who conspired to destroy working class laborers. He frequently ended his speeches by saying “and whatever happens, the Chinese must go.” Meanwhile, politicians opposed civil rights for Asian immigrants and engaged in fearmongering by claiming that Chinese people spread germs for which they were immune but white people were not. In 1871, seventeen Chinese men and boys were massacred in Los Angeles. And many Republicans in California opposed their party’s proposed 15th Amendment—which ended racial discrimination at the polls—because it opened a doorway for Chinese men to become eligible voters. Congressman Horace F. Page of California authored the Page Act in the hopes that it would greatly restrict Chinese immigration to his state. Seven years later in 1882, the Chinese Exclusion Act further restricted Chinese immigration to the United States.

Library of Congress

What were Ulysses S. Grant’s views towards Chinese immigrants, and why did he support the Page Act?

While Grant did not comment on the Page Act upon signing it into law, he had invited such legislation to be passed during his Sixth Annual Message to Congress on December 7, 1874. Grant remarked in that speech that many Chinese people had not come to the United States voluntarily, and that Chinese women were "brought for shameful purposes, to the disgrace of the communities where [they] settled and to the great demoarlization of the young of those localities." In his Seventh Annual Message to Congress a year later, Grant expressed concerns about the “twin barbarisms” of polygamy and slavery. He first mentioned that Mormons in Utah territory were engaged in a “scandalous condition of affairs” by practicing polygamy. “That polygamy should exist in a free, enlightened, and Christian country” was an outrage that needed to be corrected with legislation protecting monogamous marriage, “innocent children [and] . . . innocent plural wives.” Continuing, he connected the fight to end polygamy with the fight to end sex trafficking then being practiced through “the importation of Chinese women, but few of whom are brought to our shores to pursue honorable or useful occupations.” Whereas Grant believed Mormon women were innocent victims in oppressive polygamous marriages, he does not seem to express the same sympathy for Chinese women victimized through the sex trade.

Grant expanded his thoughts in a conversation with Chinese general and diplomat Li Hongzhang during his two-and-a-half-year world tour. Visiting Tientsin, China, in June 1879, Grant lamented that prejudice and violence against Chinese Americans was commonplace. “There is a class of thriftless, discontented adventurers, agitators, and communists, who do not work themselves and go about sowing discontent among honest workingmen,” he claimed. “Your Excellency may rest assured that the great mass of the American people will never consent to any injustice toward China or any class.”

Continuing, Grant acknowledged that he was “ready to admit that the Chinese have been of great service to our country. I do not know what the Pacific coast would be without them. They came to our aid at the time when their aid was invaluable” in building the West’s infrastructure. Expressing skepticism about anti-immigrant workers who claimed California was “overstocked” with Chinese labor, Grant remarked that “I rather suspect that many generations must pass before so great an empire as California would have too much labor.” The biggest concern for Grant was that “the trouble about your countrymen coming to America is that they come under circumstances which make them slaves. They do not come of their own free will. They do not come to stay, bringing their wives and children. Their labor is not their own, but the property of capitalists . . . We had slavery some years since, and we only freed ourselves from slavery at the cost of a dreadful war,” Grant warned. “Having made those sacrifices to suppress slavery in one form, we do not feel like encouraging it in another.” While the end of chattel slavery seemingly created the right of all individuals to make contracts for their labor, Grant’s comments suggest that he believed some contracts were unfair, coercive, and merely another form of slavery.

Library of Congress

Ulysses and Julia Grant visited China on their world tour from April 30 through June 15, 1879, stopping to visit Hong Kong, Shanghai, Peking, and Tientsin along the way. General Grant’s comments about his experiences in China were decidedly mixed. Privately, he stated to former Secretary of the Navy Adolph E. Borie that “Tientsin is a more populous city than Shanghai and more repulsively filthy,” and wrote to longtime friend Daniel Ammen that “it is not a country nor a people calculated to invite the traveler to make a second visit.” However, he also expressed to Ammen his admiration for the industry, work ethic, and desire for education among the Chinese people. “My belief is that . . . Europe will [soon] be complaining of the too rapid advance of China.”

Grant nevertheless seems to have been genuinely moved by his experiences in Asia. He remarked that Hong Kong “is really the most beautiful place I have yet seen in the East.” When a land dispute emerged between China and Japan during the world tour, Grant agreed to work as a mediator to help find a peaceful solution. And in numerous public speeches he expressed gratitude for the warm welcome he received from the Chinese people. During one speech he announced that “my visit to China has been full of interest. I have learned a great deal of the civilization, the manners, the achievements, and the industry of China that I had never known before. My visit to China has increased my estimate of the civilization and the character of the Chinese people, and I shall leave the country with increased feelings of friendship towards them.”

David A. Gerber, American Immigration: A Very Short Introduction. New York: Oxford University Press, 2011.

Hidetaka Hirota, Expelling the Poor: Atlantic Seaboard States and the Nineteenth Century Origins of American Immigration Policy. New York: Oxford University Press, 2016.

John Y. Simon, ed. The Papers of Ulysses S. Grant, Volume 29: October 1, 1878 - September 30, 1880. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 2008, pgs. 122-170.

Lynne Yuan, "China's Lost Women in the Far West," HistoryNet, October 2019.

Ming M. Zhu, "The Page Act of 1875: In the Name of Morality," Legal History Workshop, 2010.