Last updated: October 12, 2022

Article

Twin Cities Ordnance Plant: Integrating the WWII Workforce

Courtesy of Hennepin County Library, Minneapolis Newspaper Photograph Collection.

The Twin Cities Ordnance Plant was established in 1941, specifically for World War II defense production. At its peak, the plant employed 26,000 Minnesotans, including record numbers of African Americans (both men and women) in an integrated setting.

Defense Production

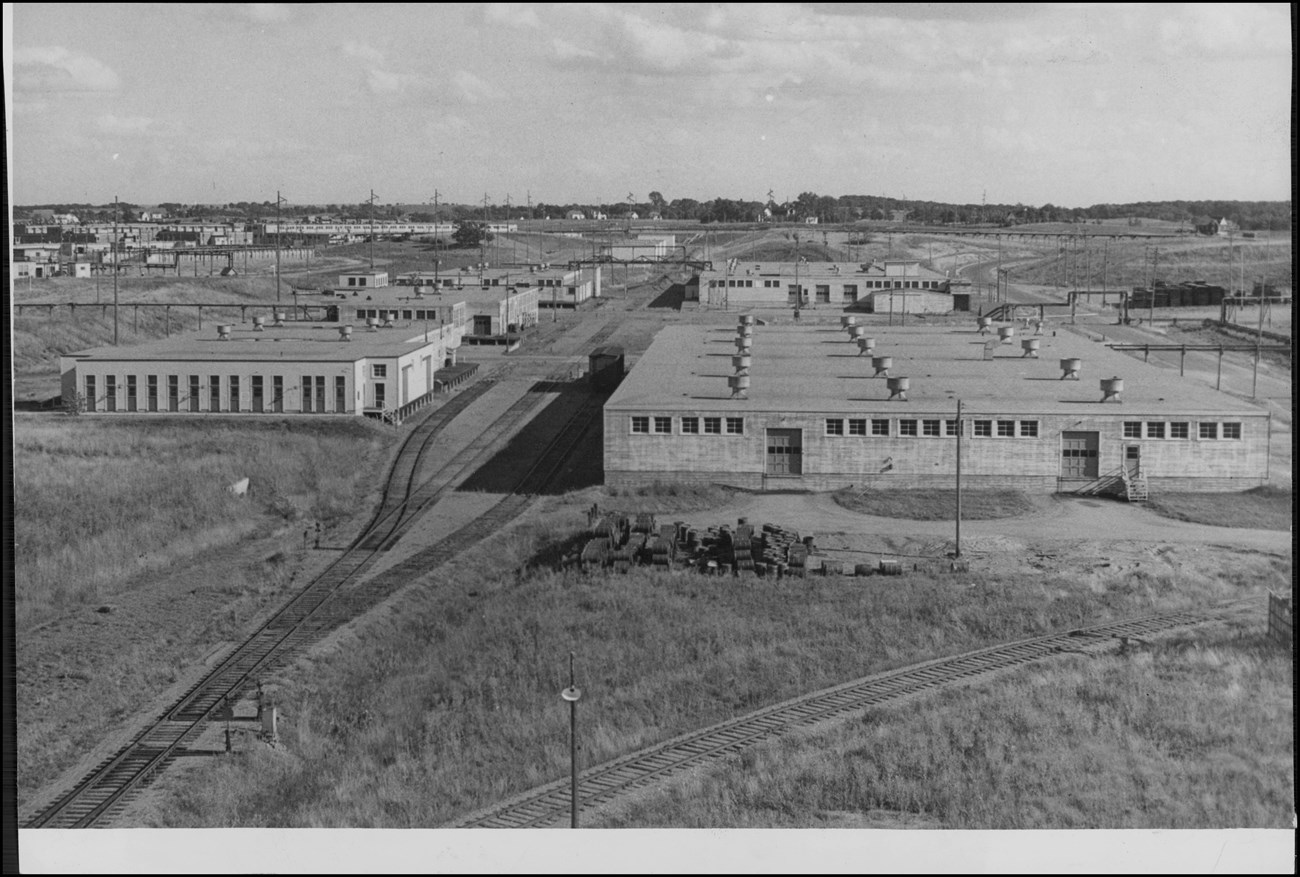

The outbreak of World War II catalyzed defense production across the United States. The Lend-Lease Act authorized the government to hire private contractors to build and run government-owned ammunitions manufacturing plants. Workers converted existing factories for wartime uses and quickly erected new facilities, including the Twin Cities Ordnance Plant (TCOP) in New Brighton, Minnesota, located about ten miles north of Minneapolis and St. Paul. The plant originally consisted of 100 buildings, completed over a six-month period. It eventually expanded to 262 total buildings, occupying 2,400 acres.

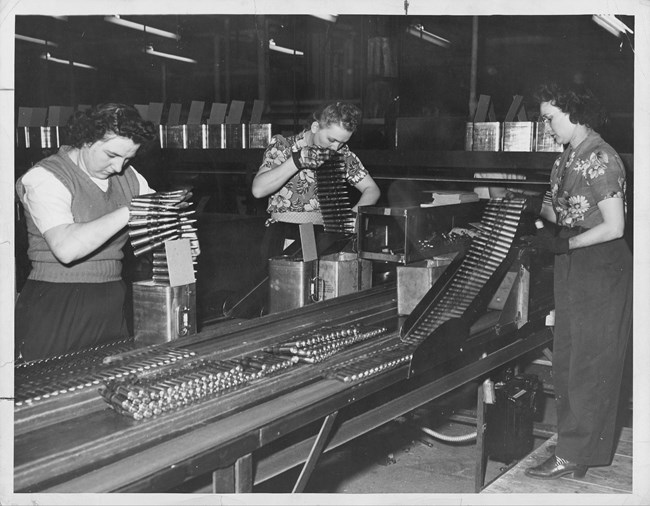

The federal government contracted the Federal Cartridge Corporation (FCC) to operate the TCOP. Between February 1942 and September 1945, the plant manufactured military equipment and supplies, namely .30-caliber and .50 caliber ammunition. By 1945, workers began to produce metal parts for 105-mm and 155-mm artillery shells.

Courtesy of Hennepin County Library, Minneapolis Newspaper Photograph Collection.

Wartime Opportunities

In addition to supplying troops overseas, the TCOP created new opportunities within the domestic workforce. At its peak in July 1943, the plant employed 26,000 people, equivalent to about 1% of Minnesota’s population at the time. Over half of these workers were women, known as Women Ordnance Workers (WOWs).

Many WOWs had not worked outside of the home before, let alone in industrial settings. The local press applauded women for stepping up and skillfully doing a “man’s job.” Although WOWs could take shifts at any hour of the day or night, they were still expected to keep up with their domestic duties. To help women balance their commitments to the home and workplace, the TCOP created a women’s consulting department. Women consultants onboarded new employees, advised on domestic issues, and recommended childcare services for working mothers.

The TCOP was fully integrated and employed over 1,200 African American men and women—over 20% of the state’s entire Black population. For many years, the Black press and the Minneapolis and St. Paul chapters of the National Urban League, a civil rights organization, campaigned for employers to hire African Americans into jobs that offered higher wages and opportunities to be promoted. They had limited success until World War II, when wartime labor shortages lowered racial barriers to jobs. In June 1941, Executive Order 8802 banned discrimination based on “race, creed, color, or national origin” in the defense industries. While many defense plants resisted or refused to enforce this policy, the TCOP led the way to provide equal opportunities for Black workers at all levels.

Courtesy of Hennepin County Library, Minneapolis Newspaper Photograph Collection.

Integrating the Workforce

The TCOP’s fair employment practices were pioneered by two members of the Minneapolis Urban League: Cecil E. Newman, a Black civic leader and newspaper publisher, and Charles L. Horn, the white president of the FCC. Horn refused to segregate Black workers or prevent them from becoming supervisors. According to Newman, Horn maintained that “Negro workers are citizens and thereby entitled to all the rights and privileges of taxpayers—which include the right to work and earn a living.”[1]

For African Americans, the TCOP offered higher wages and the opportunity to demonstrate that they deserved to keep their jobs after the war. Newman hoped “to prove his point that Negro men and women were capable of working hard at skilled trades and of doing that work shoulder to shoulder with white men and women.”[2] When Horn tapped him to advise on the hiring and placement of African Americans at the plant, Newman chose to forgo payment. He served in this position for eleven months before becoming Director of Negro Personnel.

When President Franklin D. Roosevelt visited the TCOP in 1942, he asked Horn about the unusually high number of women and people of color at the plant. After the visit, Roosevelt appointed Horn to the Fair Employment Practices Committee, which was tasked with the enforcement of Executive Order 8802 across the country.

In June 1943, the TCOP received the Army-Navy “E” Award, an honor that only two percent of defense plants earned for their exceptional work in munitions manufacturing. In addition to production, the award recognized factors such as “maintenance of fair labor standards” and “training of additional labor forces.”[3] Because the integration of Black workers helped the plant to achieve excellence in both production and fair employment, this accomplishment only bolstered African Americans’ case for racial equality.

Courtesy of Hennepin County Library, Minneapolis Newspaper Photograph Collection.

Life at the Plant

With its sprawling campus and large workforce, day-to-day operations at the TCOP relied on substantial infrastructure. The plant had its own hospital, fire department, and security guards. A bus system and rail terminal transported workers and materials between everything from temporary housing to an area for test-firing.

The TCOP maintained a high production rate, which could be demanding for workers. Efforts to prevent production disruptions and labor disputes included a no-strike agreement and committee of union and non-union members to address grievances. To boost morale, the plant also issued a newspaper, organized intramural sports teams, and formed a choir. Defense workers could hear music over the din of machinery at the start and end of their shifts, as management set the rate of production on an industrial jukebox.

Although the TCOP advanced some opportunities for African Americans, other activities that celebrated diversity at the plant tokenized workers. One feature in the Minneapolis Star-Journal depicted employees from different backgrounds walking arm-in-arm. The caption identified white employees by their occupation or age but referred to workers of color by only their race or ethnicity. In 1943, the TCOP also celebrated “I am an American Day.” Another newspaper feature recognized workers who immigrated from Poland, Russia, Greece, and the Philippines and became naturalized citizens. Both examples outwardly presented ideas of home front unity and patriotism, but also obscured that workers of color, particularly African Americans, did not experience the same opportunities or freedoms outside of the plant. Wartime activism linking the defeat of fascism abroad and racism at home—also known as the “Double V” campaign—continued after the war, laying the groundwork for the Civil Rights movement.

Courtesy of Hennepin County Library, Minneapolis Newspaper Photograph Collection.

Postwar Use

At the end of the war, the TCOP shifted gears to help the nation prepare for its next military conflict. The plant collected ammunition for testing and other machinery for storage. The facility was renamed the Twin Cities Arsenal in 1946 and later the Twin Cities Army Ammunition Plant in 1963.The plant cycled through periods of reactivation with US involvement in the Korean, Vietnam, and First Persian Gulf Wars. Labor strikes and anti-Vietnam War protests also disrupted periods of production.

By the 1980s, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) began to investigate the plant’s environmental impacts from dumping industrial waste. The EPA determined that toxic chemicals had seeped into the soil, sediment, and groundwater, contaminating the fresh water supply. In 1983, the agency established a 25-square mile Superfund site around the plant and nearby communities to prevent further human exposure. The US Army, Minnesota Pollution Control Agency, and EPA eventually reached a Federal Facility Agreement—the nation’s first—in December 1987, requiring the military to clean up the site.

There have been several efforts to redevelop the site over the years. The plant was surveyed by the Historic American Engineering Record (HAER) in 1984. HAER documents significant sites, structures, and processes related to engineering and industry. Even if those resources are demolished, HAER reports, measured and interpretive drawings, and photographs allow us to learn from the US’s engineering legacy.

The content for this article was researched and written by Jade Ryerson, Cultural Resources Office of Interpretation and Education.

[1] Cecil E. Newman, “Industrialist Charles Horn Changed Employment Patterns Here by Job Democracy,” Minneapolis Spokesman, February 27, 1953; previously published in Opportunity Magazine (April-June 1944), Minnesota Digital Newspaper Hub, https://www.mnhs.org/newspapers/lccn/sn83025247/1953-02-27/ed-1/seq-11.

[2] Geri Hoffner, “Editor Backs Up All Minorities,” Minneapolis Morning Tribune, August 31, 1947, ProQuest Historical Newspapers: Minneapolis Star Tribune, https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/august-31-1947-page-9-111/docview/1852481492/se-2.

[3] “Wear with Pride,” Minneapolis Spokesman, June 11, 1943, Minnesota Digital Newspaper Hub, https://www.mnhs.org/newspapers/lccn/sn83025247/1943-06-11/ed-1/seq-2.

Crown, Deborah L. “The World War II Ordnance Department's Government-Owned Contractor-Operated (GOCO) Industrial Facilities: Twin Cities Ordnance Plant Transcripts of Oral History Interviews.” US Army Materiel Command Historic Context Series. Report of Investigations. Number 8C. May 1996. https://archive.org/details/DTIC_ADA315713/mode/2up.

Delton, Jennifer A. “Labor, Politics, and African American Identity in Minneapolis, 1930-1950.” Minnesota History 57, no. 8 (Winter 2002): 418-434. Accessed August 24, 2022. http://collections.mnhs.org/MNHistoryMagazine/articles/57/v57i08p418-434.pdf.

Hess, Jeffrey A., and Robert C. Mack of the MacDonald and Mack Partnership. “Twin Cities Army Ammunition Plant, New Brighton, Ramsey County, MN.” Written Historical and Desriptive Data, Historic American Engineering Record, National Park Service, US Department of the Interior, 1984. From Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress (HAER No. MN-4; https://www.loc.gov/item/mn0078/).

Hoffner, Geri. “Editor Backs Up All Minorities.” Minneapolis Morning Tribune. August 31, 1947. ProQuest Historical Newspapers: Minneapolis Star Tribune. https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/august-31-1947-page-9-111/docview/1852481492/se-2.

Kimbrell, K. Diane, Matthew Snellgrove, Robert C. Vogel, and Deborah L. Crown. “Twin Cities Army Ammunition Plant: Supplementary Photographic Documentation of Archetypal Buildings, Structures, and Equipment for US Army Materiel Command National Historic Context for World War II Ordnance Facilities.” US Army Materiel Command Historic Context Series. Report of Investigations. Number 8B. May 1995. https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/pdfs/ADA315682.pdf.

Minneapolis Morning Tribune. “‘Lil’ Fills the Bill at New Brighton.” September 5, 1943. ProQuest Historical Newspapers: Minneapolis Star Tribune. https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/september-5-1943-page-31-52/docview/1848995498/se-2.

Minneapolis Morning Tribune. “Women War Workers Are ‘Mighty Good Men.’” August 25, 1942. ProQuest Historical Newspapers: Minneapolis Star Tribune. https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/august-25-1942-page-3-16/docview/1852097536/se-2.

Minneapolis Spokesman. “Wear with Pride.” June 11, 1943. Minnesota Digital Newspaper Hub, https://www.mnhs.org/newspapers/lccn/sn83025247/1943-06-11/ed-1/seq-2.

Minneapolis Star Journal. “Their Slogan: ‘Keep ‘Em Shooting!’” May 22, 1942. ProQuest Historical Newspapers: Minneapolis Star Tribune. https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/may-22-1942-page-30/docview/1852123354/se-2.

Minneapolis Sunday Tribune. “Consultants Aid 7,713 Women Weekly at Twin City War Plant.” April 11, 1943. ProQuest Historical Newspapers: Minneapolis Star Tribune. https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/april-11-1943-page-44-84/docview/1848982415/se-2.

Nelson, Tim. “Forged and Forgotten: Twin Cities Ammo Plant Helped Win WWII.” MPR News. May 23, 2014. https://www.mprnews.org/story/2014/05/23/twin-cities-army-ammunition-plant-history.

Newman, Cecil E. “Industrialist Charles Horn Changed Employment Patterns Here by Job Democracy.” Minneapolis Spokesman. February 27, 1953. Previously published in Opportunity Magazine (April-June 1944). Minnesota Digital Newspaper Hub. https://www.mnhs.org/newspapers/lccn/sn83025247/1953-02-27/ed-1/seq-11.

Sorensen, Kara. “Twin Cities Army Ammunition Plant.” MNopedia. Minnesota Historical Society. Accessed August 10, 2022. http://www.mnopedia.org/place/twin-cities-army-ammunition-plant.

Twin Cities Army Ammunition Plant Restoration Advisory Board. “Site History.” Background. Accessed August 31, 2022. https://tcaaprab.org/background/#SiteHistory.