Last updated: December 31, 2025

Article

Trinity Test Downwinders

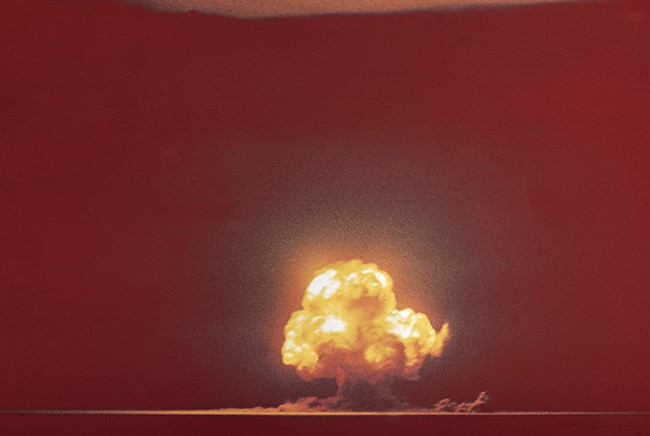

Photo by Jack Aeby. Courtesy of Los Alamos National Laboratory. Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.0 Generic (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0).

On July 16, 1945, a loud, blinding explosion surprised New Mexicans around the Tularosa Basin. Trinity, the world’s first nuclear test, was top secret. Manhattan Project leaders did not inform people living nearby or downwind about the test or potential exposure to fallout.

Top Secret

Manhattan Project leaders carefully selected test sites. Remote locations like the Tularosa Basin of New Mexico offered many strategic advantages. Known only to top scientists and military officials, the Trinity Test Site was about 200 miles southeast of Los Alamos National Laboratory. The environment was flat and arid. Scientists also believed that the site’s generally low and predictable winds would limit the spread of radiation.

Despite their goal of secrecy, the blast was visible up to 160 miles away. Witnesses from as far as Albuquerque and El Paso described a huge fireball and mushroom cloud. Although few people lived in the surrounding Jornado Del Muerto Desert, some ranchers and their cattle lived 13 miles from the Trinity Test Site. Tens of thousands lived within 50 miles. They were not informed about the test until after the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Scientists and military officials prioritized secrecy. In a press release, they described the explosion as an accident involving ammunition and pyrotechnics. Although there were no injuries, the release stated that weather conditions may require some civilians to evacuate. Manhattan Project leaders eventually decided against an evacuation, which they worried would heighten suspicion or incite panic.

Courtesy of Atomic Archive (LA 1027-DEL).

Fallout

The Trinity Test marked the first time a nuclear device was ever detonated and the first time that a nuclear bomb was ever tested. Manhattan Project scientists loaded the device, known as the Gadget, with 13 pounds of weapon-grade plutonium. Only 3 pounds were necessary for the fission reaction. They knew that the Trinity Test would generate large amounts of fallout, but the fallout pattern was far less certain.

Scientists rigged the Gadget to the top of a 100-foot tower. Because the Trinity Test was relatively close to the ground, it shot large amounts of radiation up into the atmosphere. Radioactive fallout descended to the northeast over an area about 250 miles long and 200 miles wide. Scientists tracked part of the fallout pattern as far as the Atlantic Ocean. The greatest concentration of fallout settled on the Chupadera Mesa, 30 miles from the test site. After Trinity, the military changed tactics. They began timing explosions above the ground to reduce the dispersal of radioactive fallout.

In New Mexico, radiation landed on vegetables and cattle and contaminated the water supply. Many people in rural New Mexico lacked running water and collected rainwater that ran off of roofs in large cisterns, or holding tanks. Most locals also grew most of their own food and raised livestock for meat. Eating foods with high levels of radiation has been linked to cancer, stillbirth, and birth defects.

Manhattan Project scientists took precautions to study the outcomes of the Trinity Test. To protect against radiation, they used lead-lined tanks to collect rock samples and required the use of protective gear for those working around the detonation point. Scientists also purchased some of the cattle that sustained severe burns to study the effects of radiation. They did not collect any data about civilian exposure, concerned that this might alarm the public. The novelty of the Trinity Test meant that civilians did not understand the severity of radiation exposure, even after the government disclosed that the blinding explosion on the morning of July 16 had been an atomic bomb.

Photo by Terry Robinson, Attribution-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic (CC BY-SA 2.0).

Living Downwind

In the years after the Trinity Test, people living in nearby Lincoln, Socorro, Otero, and Sierra counties began to report health issues. Diseases such as heart disease, leukemia, and other cancers appeared in families who had no prior history. People who reported these incidents became known as “Downwinders” because they lived near or downwind from the test site.

For many Downwinders, access to medical care could be difficult. Without local healthcare providers, Downwinders in the Tularosa Basin had little choice but to drive long distances to see doctors. Many also struggled to afford expensive medical care. Due to illness, some Downwinders became unable to work. In the view of new employers, health issues became preexisting conditions, which could limit a Downwinder’s ability to access other job opportunities.

A group of New Mexicans known as the Tularosa Basin Downwinders Consortium states that they were unknowingly exposed to radiation from fallout, resulting in illness, emotional and financial distress, and death. This group is pursuing recognition under the Radiation Exposure Compensation Act (RECA) of 1990. RECA provides financial compensation for medical treatment for people exposed to radiation from uranium mining and atmospheric testing in Nevada. Between 1951 and 1957, the government conducted atmospheric tests at a site about 65 miles north of Las Vegas. At scientists’ urging, the government banned atmospheric tests in 1963.

In 2011, the US Senate unanimously voted to designate January 27 as the National Day of Remembrance for Downwinders. This designation only recognizes people who were impacted by the Nevada Test Site. In May 2022, the US Congress extended the period to claim compensation under RECA from July 2022 until May 2024.

The content for this article was researched and written by Jade Ryerson, Cultural Resources Office of Interpretation and Education.

The Architectural League of New York. “The Aftermath of the Manhattan Project in Southern New Mexico | Socorro County.” Interview with Tina Cordova by Ane González, 2020. American Roundtable: Lower Rio Grande, New Mexico. https://archleague.org/article/socorro-county/?printpage=true.

Atomic Heritage Foundation. “Tularosa Basin Downwinders.” Health Issues. July 31, 2018. https://www.atomicheritage.org/history/tularosa-basin-downwinders.

Eckles, Jim. Oral history interview with Cynthia C. Kelly. December 7, 2017. Voices of the Manhattan Project Oral History Project. Atomic Heritage Foundation. https://www.manhattanprojectvoices.org/oral-histories/jim-eckles-interview.

Jones Vincent C. Manhattan: The Army and the Atomic Bomb. United States Army in World War II. Washington, DC: Center of Military History, United States Army, 1988.

US Department of Justice. “Radiation Exposure Compensation Act.” Civil Division. Last updated August 3, 2022. https://www.justice.gov/civil/common/reca.

Tags

- manhattan project national historical park

- manhattan project

- world war ii

- wwii

- world war 2

- ww2

- american world war ii heritage city

- awwiihc

- world war ii home front

- wwii home front

- world war ii history

- wwii history

- science and technology

- history of science

- history of technology

- los alamos

- tularosa basin

- new mexico

- people of los alamos

- stories of los alamos

- downwinder

- downwinders

- gadget

- trinity test

- trinity site