Last updated: April 27, 2023

Article

Tree Rings and the Tales They Tell

NPS

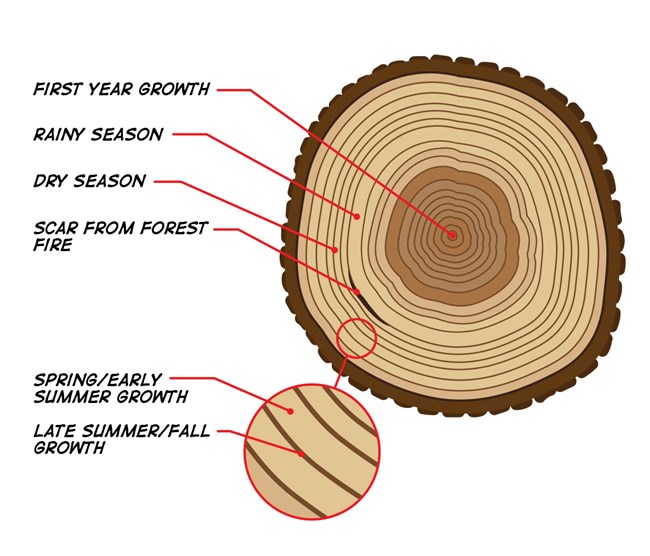

If you’ve ever seen a tree stump, you probably noticed the bullseye of rings on top. Most people know that you can tell the age of a tree by counting its rings. But there’s more information in a cross-section of a tree trunk than just its age.

Ecologists with the National Capital Region have been searching for clues about past climate conditions in the rings of 1,518 trees, representing 36 different species. Using a tool with a pencil-sized cutting tube, called an incremental borer, ecologists extracted a thin “tree core” sample from each living tree. (The impact to the tree is akin to common insect activity and is similar to a medical biopsy for humans.) Each cylindrical tree core displays a pattern of narrow and wide rings for each year of its life.

Science Education Resource Center, Carleton College

Looking at the patterns in a tree core is much like reading a history book about a certain time period. The width, color, and pattern of tree rings can tell us whether the tree was thriving or struggling. An especially wet year might result in broader rings, since the tree is able to grow more than it could have in a drier year. A blackened scar can indicate a wildfire, and other marks could point to an insect infestation.

In addition to telling us about environmental stressors, tree rings can also tie a tree to specific historical events. Tree cores from two trees that lived at different times can be linked together to create a longer timeline by matching the patterns that grew at the same period (see image below).

NPS

This dating technique, known as “dendrochronology,” was used by NPS scientists in the southwestern US to learn about ancient Puebloan settlements. The logs used in ancient and historic buildings preserve tree ring chronologies from a variety of time periods, that can then be linked together to tell a longer story.

In-tree-guing Findings

National Capital Region ecologists looked at tree rings to determine the average age of forests near long-term forest monitoring plots, which have been shown to harbor more old-growth structure when compared with forests outside of parks. In our study, we focused on oak and evergreen tree species, because they provide more reliable tree rings.

Expand the table below to find out for each park, the species and age of the oldest tree cored for this project and the average tree age.

| Park | Oldest tree year | Oldest tree age in 2022 | Common name | Latin name | Average age in 2022 of oldest trees cored* | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antietam National Battlefield | 1885 | 137 |

|

Carya tomentosa | 86 | ||

| Catoctin Mountain Park | 1825 | 197 |

|

|

134 | ||

| Chesapeake & Ohio Canal National Historical Park | 1844 | 178 |

|

Quercus montana | 80 | ||

| George Washington Memorial Parkway | 1868 | 154 | Shagbark hickory | Carya ovata | 97 | ||

| Harpers Ferry National Historical Park | 1864 | 158 | Chestnut oak | Quercus montana | 109 | ||

| Manassas National Battlefield | 1865 | 157 | White oak | Quercus alba | 94 | ||

| Monocacy National Battlefield | 1880 | 142 | Chestnut oak | Quercus montana | 78 | ||

| National Capital Parks - East | 1861 | 161 | Chestnut oak | Quercus montana | 82 | ||

| Prince William Forest Park | 1783 | 239 |

|

Quercus alba | 123 | ||

| Rock Creek Park | 1830 | 192 | Yellow poplar | Liriodendron tulipifera | 114 | ||

| Wolf Trap National Park for the Performing Arts | 1842 | 180 | White oak | Quercus alba | 95 |

*This is the average of the oldest tree cored at each plot, across all plots per park.

Sometimes, tree rings reveal how the land around a tree was used in the past. The area around a single tree in a forest, for example, may have undergone disturbances, such as agriculture, deforestation, or urban encroachment; these events can sometimes be detected in tree rings.

In NCRN forests, individual trees sometimes provide clues about this past land use. In some forest stands, one tree may be found to be older than the surrounding trees, perhaps representing a tree that stood through past land-use variation (e.g., agriculture), whereas neighboring trees that are substantially younger, would represent trees that regenerated when agricultural lands reverted to natural forest cover. In these interesting cases, the “average” age of the trees would not best represent the age of a forest.

Trees: A Standing Witness to His-tree

When we think about the past, it’s important to know what the land looked like and what changes it has undergone. Our memories are stored within our bodies, and in the same vein, the memories of the land are stored within the trees. Let’s take a closer look at the lived experiences of three of the oldest trees we studied. (Good things come in trees!)

Chris Evans, University of Illinois, Bugwood.org

White oak (Quercus alba), 239 years

Prince William Forest Park

I am a white oak, broad-limbed and majestic. I can live as long as 450 years and grow as tall as 100 feet.

Every four years, I am visited by NCRN ecologists. I watch as they measure the width and health of trees around me. I hear that I’m the oldest tree they’ve found so far. At 239 years old, I’ve seen a tree-mendous amount already. In fact, I’ve been here longer than the United States has had a president. I’ve watched people interact with the land around me in many different ways, including searching for gold and pyrite, harvesting tobacco, and establishing two large mills.

I watched as the Civilian Conservation Corps started constructing Prince William Forest Park in 1936. Cabin camps were built on the surrounding rolling hills. When people first started using these camps, they were still segregated by race. In the 1940s, I watched as sleepy summer camps were transformed into secret military training grounds. People darted around me, learning the art of spying and survival behind enemy lines. It’s hard to believe that was nearly a century ago. Nowadays, most of the people I see are taking a relaxing stroll, admiring my massive, outstretched limbs.

Paul Wray, Iowa State University, Bugwood.org

Tulip Poplar (Liriodendron tulipifera), 192 years

Rock Creek Park

I celebrated my 192nd birthday this year! Trees of my kind, the tulip poplar (also called yellow poplar), are some of the tallest hardwood trees in North America. I can reach heights well over 100 feet and enjoy growing in moist soil on slopes and low-lying areas.

I started growing in 1830, before Rock Creek Park even existed. In the early 1800s, American settlers transformed the land around me for tobacco farming, and then again for wheat and corn production. What effects do you think this might have had on the soil that I draw my nutrients from?

In the early 1860s, the area around me was deforested during the US Civil War. I was spared, but many other trees were felled. Logs and branches were laid out systematically by Union soldiers, creating a barrier against a Confederate march. That’s a lot of action in just the first quarter of my life!

When I turned 60, I witnessed the establishment of Rock Creek Park, the 3rd national park in the US. Now I watch as thousands of visitors recreate here every year. My huge branches are quite “poplar,” providing shade for both visitors and wildlife.

Chris Evans, University of Illinois, Bugwood.org

Chestnut oak (Quercus montana), 158 years

Harper's Ferry National Historical Park

I am a stately giant. I am slow growing and long-lived, and you can find me on a wooded slope or along a rocky ridge.

I started growing right in the midst of the US Civil War in 1864, the same year that Confederate General Jubal Early led his troops through Harpers Ferry on his way to attack Washington DC. Civil rights giants like Frederick Douglass and W.E.B. Du Bois were drawn to Harpers Ferry. Perhaps they laid their eyes on me.

I drink from the same rivers that produced power for Harper Ferry’s mills and factories. Neighboring trees were chopped down and used to power industry and stoves for the townsfolk. Stationed between the Shenandoah and Potomac rivers, I watch as humans use this gap in the Blue Ridge mountains as an avenue for travel and transport, from 1864 to now.

For more information

- Elmore AJ, Brosi SL, Guinn SM, Matthews E, Schmit JP, Brolis A, Foster JR. 2023. Dendroecological data for forested parks in the National Capital Region Network. Natural Resource Data Series. NPS/NCRN/NRDS—2023/1393. National Park Service. Fort Collins, Colorado.

- Watch a video about how national parks across the country have used dendrochronology.

- Learn about the different types of values that trees add to our parks.

NPS

Tags

- antietam national battlefield

- catoctin mountain park

- chesapeake & ohio canal national historical park

- george washington memorial parkway

- harpers ferry national historical park

- manassas national battlefield park

- monocacy national battlefield

- national capital parks-east

- prince william forest park

- rock creek park

- wolf trap national park for the performing arts

- ncrn

- nature

- science

- tree rings

- dendrochronology

- tree

- chestnut oak

- white oak

- quercus

- tulip poplar

- forest

- forest monitoring